7 Best Fly Fishing Foods That Trout Can’t Resist in 2025

By Adam Hawthorne | Last Modified: May 4, 2025

If there’s one thing I’ve learned after three decades of fly fishing, it’s that trout can be maddeningly selective about what they eat. Last September, I spent an entire morning watching fat rainbows sip tiny bugs off the surface of the Au Sable while completely ignoring my carefully presented fly. I switched patterns six times before finally cracking the code with a size 20 Trico spinner. The lesson? Understanding what trout actually feed on can make the difference between a memorable day and an exercise in frustration.

There’s a saying among seasoned anglers that “matching the hatch” is everything in fly fishing. While that’s not always true (sometimes an attractor pattern will outfish a perfect imitation), knowing the natural food sources that make up a trout’s diet is fundamental to consistent success. Over the years, I’ve filled dozens of fly boxes with countless patterns, but I keep coming back to flies that imitate these seven food sources.

Understanding Trout Feeding Habits Before Choosing Flies

Before diving into specific food types, it’s worth understanding how trout actually feed. These fish are opportunistic but can also be incredibly selective. My fishing buddy Dave, who guides on the Pere Marquette, always says, “Trout are looking for the most calories for the least effort.” This explains why they’ll sometimes ignore small mayflies to focus on larger food items like hoppers or sculpin.

Trout feeding behavior changes dramatically based on:

- Water temperature (they feed most actively between 55-65°F)

- Time of day (dawn and dusk typically see increased activity)

- Water clarity (clearer water usually means more selective feeding)

- Seasonal availability of food sources

- Fishing pressure (heavily fished trout become more discriminating)

I’ve noticed that early season trout on Michigan’s northern streams are far less picky than the same fish in August after seeing hundreds of flies drift overhead. The education they receive from anglers makes a huge difference in what they’ll accept.

Water type also dictates feeding patterns. Fast pocket water creates feeding opportunities where trout must make split-second decisions, while slow, clear pools allow fish to carefully inspect potential food. My biggest trout have typically come from the latter situation, but only when I’ve managed to present the exact right fly.

The 7 Best Fly Fishing Foods

1. Mayflies: The Bread and Butter of Trout Diets

If you ask most fly fishers about the most important trout food, mayflies usually top the list. These aquatic insects spend most of their life as nymphs on stream bottoms before hatching into winged adults that mate and die within 24 hours. This lifecycle creates multiple feeding opportunities for trout.

Mayflies come in hundreds of species, but for practical purposes, I group them into three main categories based on size:

Small (size 18–24): Tricos, Blue-Winged Olives

Medium (size 14–18): Pale Morning Duns, March Browns

Large (size 10–14): Green Drakes, Hexagenia

The Hex hatch on northern Michigan’s streams is legendary – I’ve seen 2-inch mayflies covering every surface and trout so focused on them they’d practically hit a bare hook. During one memorable night on the Au Sable, the hatch was so thick the sound of rising fish echoed through the cedar swamp like popcorn popping. We caught fish until our arms were sore, but only on oversized cream-colored patterns that matched the naturals.

The best mayfly patterns to carry include:

For nymph fishing:

- Pheasant Tail Nymph (sizes 14-18)

- Hare’s Ear (sizes 12-16)

- Copper John (sizes 16-20)

For dry fly fishing:

- Parachute Adams (sizes 12-20) – my desert island fly

- Blue-Winged Olive (sizes 18-22)

- Extended Body Mayfly (sizes 10-14 for Hex and Drake hatches)

I’ve found that having both nymph and dry versions of the same insect is crucial. During a Trico hatch on the South Branch two summers ago, fish completely ignored the adults but hammered the tiny black spinners once they fell spent on the water. Without understanding this part of the lifecycle, I’d have blanked on what turned into an incredible morning.

2. Caddisflies: The Underappreciated Workhorses

While mayflies get all the glory in fly fishing literature, caddisflies are often more abundant and available to trout throughout the year. Unlike the delicate upright wings of mayflies, caddis hold their wings tent-like over their bodies and tend to skitter across the water when laying eggs.

Caddis have three distinct life stages that trout key on:

- Larva: Worm-like creatures that build protective cases from sand, sticks or debris

- Pupa: The transitional stage as they rise in the water column to hatch

- Adult: The winged insect that returns to the water to lay eggs

What makes caddis particularly effective is their behavior. They don’t just float passively like mayflies – they actively skate and bounce along the surface. This movement triggers a predatory response in trout that can lead to explosive strikes.

The most effective caddis patterns in my experience include:

For subsurface fishing:

- Caddis Pupa (sizes 14-18)

- LaFontaine Sparkle Pupa (sizes 14-16)

- Soft Hackle (sizes 14-18)

For surface fishing:

- Elk Hair Caddis (sizes 14-18)

- X-Caddis (sizes 16-20)

- Stimulator (sizes 12-16)

One early June evening on the Jordan River transformed how I fish caddis patterns. I was getting refusals on a perfectly decent Elk Hair Caddis when an old-timer fishing nearby suggested I try skating it instead of dead-drifting. “Twitch it like it’s trying to get away,” he said. The difference was immediate – what had been subtle rises became savage attacks. Now I always impart action to my caddis patterns, and I catch significantly more fish as a result.

3. Stoneflies: Big Bugs for Big Fish

If you’re after trophy trout, having stonefly patterns in your box is non-negotiable. These are the largest aquatic insects trout encounter in most streams, and they represent a protein-packed meal fish find hard to resist.

Stoneflies prefer clean, highly-oxygenated water, making them indicators of healthy stream ecosystems. Unlike mayflies with their delicate swimming, stonefly nymphs crawl along the bottom, making them vulnerable when crossing open areas or during their migration to shore before hatching.

The prime times for fishing stonefly patterns are:

- Early spring (when many species hatch)

- After heavy rains (when nymphs get dislodged)

- At night (when many adults return to lay eggs)

My go-to stonefly patterns include:

For nymphing:

- Kaufmann’s Stone (sizes 6-10)

- Twenty-Incher (sizes 4-8)

- Girdle Bug (sizes 6-10)

For dry fly fishing:

- Stimulator (sizes 6-10)

- Sofa Pillow (sizes 6-8)

- Chernobyl Ant (sizes 6-10) – technically an attractor but works great

My best day ever on Wyoming’s Snake River came during a massive golden stone hatch. The guides had told us it was still a week away, but we found ourselves in the middle of it after a sudden temperature spike. I switched to a size 6 Stimulator – easily the largest dry fly I’d ever fished – and caught browns up to 22 inches. The takes were so violent they nearly yanked the rod from my hands. I learned that day to always pack a few giant dries no matter what the “experts” say about expected hatches.

4. Terrestrials: Summer and Fall Game-Changers

During the dog days of summer when aquatic insect activity slows, terrestrial insects become a critical food source for trout. These land-based bugs – grasshoppers, ants, beetles, and crickets – accidentally end up in the water through wind, rain, or missteps and represent easy protein for opportunistic fish.

What makes terrestrials particularly effective is their unexpectedness. A grasshopper hitting the water makes a distinct “plop” that alerts nearby trout to an easy meal. Unlike aquatic insects that emerge predictably, terrestrials are random events that fish won’t pass up.

The most productive terrestrial patterns in my experience:

- Hoppers (sizes 6-12): Dave’s Hopper, Chubby Chernobyl

- Ants (sizes 16-20): Parachute Ant, Cinnamon Ant

- Beetles (sizes 12-16): Peacock Beetle, Japanese Beetle

- Cricket patterns (sizes 10-14)

The most overlooked terrestrial? Definitely ants. I’ve had late-season days on heavily pressured streams where nothing worked until I tied on a tiny black ant pattern. My buddy Tom laughed when he saw the minuscule fly, but stopped chuckling when I caught five nice browns in an hour from a pool he’d just fished through with traditional patterns.

Terrestrials work best when presented with a bit of commotion – a subtle splat rather than a delicate touchdown. I like to target grassy undercut banks and overhanging branches where natural insects would likely fall in. The strikes can be heart-stopping, especially when fishing large hopper patterns.

One September on Montana’s Madison River, our guide suggested I try a hopper-dropper rig with a size 8 hopper and a size 18 beadhead nymph. I was skeptical about the ungainly setup but followed his advice. The result was a 20-fish day with the bigger browns taking the hopper and smaller rainbows hitting the dropper. That technique has become a standard part of my summer arsenal ever since.

5. Sculpins and Baitfish: For Trophy Hunters Only

While insects make up the bulk of a trout’s diet, larger fish often shift their feeding patterns to target other fish. Sculpins – small bottom-dwelling baitfish with large pectoral fins – are particularly important in this category. They’re high in protein and abundant in many trout streams.

Fishing baitfish patterns requires a different approach than insect imitations. Rather than dead-drifting, you’ll want to actively retrieve these flies with twitches and pauses to mimic an injured or fleeing baitfish. This typically means using heavier tippet (3x or even 2x) and being prepared for aggressive strikes.

The most effective baitfish patterns I’ve used include:

- Woolly Bugger (sizes 2-8): The classic that imitates everything from sculpins to leeches

- Sculpin patterns (sizes 2-6): Muddler Minnow, Cone Head Sculpins

- Streamer patterns (sizes 2-6): Zoo Cougar, Sex Dungeon, Clouser Minnow

Streamer fishing isn’t everyone’s cup of tea – it’s physically demanding and often produces fewer but larger fish. That said, my personal best brown trout (26 inches from the Pere Marquette) fell to a white and olive streamer fished during high, slightly off-color water conditions in early spring.

When fishing these patterns, focus on:

- Deeper pools and runs

- Undercut banks

- Confluence points where smaller streams enter larger ones

- Dawn and dusk (prime feeding times for large predatory trout)

If you really want to up your streamer game, invest in a sinking tip line or add split shot about 8 inches above your fly. Getting the pattern down in the water column is crucial for success. And remember – strips of varying lengths and speeds will almost always outfish a steady retrieve. I like to use what I call a “panic strip” – two quick pulls followed by a pause – which seems to trigger reaction strikes even from non-feeding fish.

6. Midges: The Year-Round Food Source

If trout had to survive on a single food source, it might well be midges. These tiny insects are available year-round, even during winter months when other insect activity ceases. While individually small, midges often appear in such massive numbers that they become the primary food source during certain times.

The challenge with midge fishing is their size – typically ranging from #18 down to microscopic #26 or smaller. This requires fine tippets (5x-7x), perfect presentations, and careful observation to detect subtle takes.

Most effective midge patterns include:

For nymphing:

- Zebra Midge (sizes 18-22)

- WD-40 (sizes 18-24)

- Mercury Black Beauty (sizes 20-24)

For dry fly fishing:

- Griffith’s Gnat (sizes 18-22)

- CDC Midge Cluster (sizes 18-22)

- Sprout Midge (sizes 20-24)

During a brutal January day on Colorado’s South Platte when the temperature barely cracked 20 degrees, I watched an elderly gentleman consistently catch fish while everyone else went home skunked. His secret? Tiny black midge patterns fished on 7x tippet with strike indicators set absurdly close to his flies. The takes were invisible to the naked eye, but he’d developed the sensitivity to detect them. That lesson in persistence and technique fundamentally changed how I approach winter fishing.

The best approach for midge fishing is to use a strike indicator or dry-dropper setup, focus on slower pools and tailouts where midges concentrate, and keep your presentations drag-free. It’s technical fishing at its finest, but when nothing else is working, midges can save the day.

7. Crustaceans: The Secret Weapons

While not available in all watersheds, where present, crustaceans like scuds (freshwater shrimp) and crayfish can constitute a significant portion of a trout’s diet. These high-protein food sources are particularly important in spring creeks, tailwaters, and stillwaters.

Scuds are small, shrimp-like creatures that thrive in streams with abundant aquatic vegetation. They typically range from olive to orange in color depending on their environment and lifecycle stage. Crayfish, meanwhile, are most important for larger trout, particularly browns.

The most productive crustacean patterns I’ve used include:

For scuds:

- Sow Bug (sizes 14-18)

- Scud patterns (sizes 14-18)

- Czech Nymphs (sizes 12-16)

For crayfish:

- Clouser Crayfish (sizes 4-8)

- Whitlock’s Near Nuff Crayfish (sizes 4-8)

- Woolly Bugger (sizes 4-8, in brown/orange variations)

I almost never considered crayfish patterns until a humbling experience on Pennsylvania’s Spring Creek. I’d watched a guide and client consistently pull nice browns from runs I’d just fished without success. When I finally broke down and asked what they were using, the guide showed me a rusty orange weighted fly meant to imitate a small crayfish. I tied one on and immediately caught three fish from water I’d thought was barren. This taught me to always research the primary food sources in a watershed before assuming I know what will work.

When fishing scud patterns, focus on spring creeks and tailwaters with abundant vegetation. Dead-drift these flies near the bottom, occasionally adding small twitches to simulate their swimming motion. For crayfish patterns, target rocky sections with a strip-and-pause retrieve that imitates their defensive backwards scoot when threatened.

How to Choose the Right Food Imitation for Any Situation

With seven major food categories, how do you decide what to tie on for any given situation? Here’s my practical approach developed over countless days on the water:

- Observe before fishing. Take five minutes to look for:

- Rising fish (indicating surface feeding)

- Insects in the air or on vegetation

- Natural debris in eddies or foam lines

- Check under rocks. This quick stream-bottom sample reveals:

- What nymphs are present

- Their approximate size and color

- Their relative abundance

- Consider the season:

- Spring: Focus on stoneflies and early mayflies

- Summer: Terrestrials become increasingly important

- Fall: Terrestrials and streamers as trout become more aggressive

- Winter: Midges and small nymphs almost exclusively

- Water conditions matter:

- Clear, low water: Smaller, more realistic patterns

- High, off-color water: Larger, more visible patterns with vibrant colors

- When all else fails: My confidence progression is:

- Parachute Adams (#16)

- Hare’s Ear Nymph (#14-16)

- Olive Woolly Bugger (#6-8)

- Parachute Ant (#16-18)

Last summer during a peculiar evening on the Pere Marquette, I observed trout rising steadily but couldn’t see any obvious insects. After cycling through mayfly patterns with no success, I noticed tiny flying ants along the shoreline. A quick switch to a #20 black ant pattern turned a frustrating session into a memorable evening. The lesson? Always be observant and willing to experiment outside your comfort zone.

Regional Variations in Trout Food Sources

What trout eat varies dramatically by region. Here in Michigan, our spring Hendrickson hatches are legendary, while out west the salmon fly hatches draw anglers from around the world. Understanding these regional differences can save you from carrying unnecessary flies and help you focus on what actually works in a given watershed.

In the Great Lakes region where I do most of my fishing, our most important hatches include:

- Hendricksons (mid-April through May)

- Sulphurs (late May through June)

- Brown Drakes (late May through early June)

- Hex (late June through early July)

- Tricos (July through September)

- White flies (August)

Whereas in the Rocky Mountain region, the hatch chart looks completely different:

- Blue-Winged Olives (April through June, then again in fall)

- Salmon flies (late May through June)

- PMDs (mid-June through August)

- Terrestrials (July through September)

- Mahogany duns (September through October)

When I traveled to Montana’s Madison River for the first time, I brought my Michigan fly boxes loaded with Hex patterns and other Great Lakes favorites. The local guide took one look and handed me a completely different selection focused on patterns I rarely used at home. It was a humbling reminder that regional knowledge trumps general fly fishing theory every time.

The Truth About Presentation vs. Pattern Selection

I’d be remiss if I didn’t address the eternal fly fishing debate: Is presentation more important than fly selection? After 30+ years chasing trout across North America, I’ve come to a nuanced conclusion.

In many situations, particularly in faster water or when fish aren’t actively feeding, presentation trumps pattern selection. A poorly presented “perfect” fly will catch fewer fish than a well-presented “decent” fly. That said, during selective feeding periods (like a specific mayfly hatch), having the right pattern becomes increasingly important.

My fishing journal from the last five years shows that approximately:

- 60% of my success comes from proper presentation

- 30% from having the right pattern

- 10% from pure luck (being in the right place at the right time)

The most dramatic example of this came during a Green Drake hatch on a small Pennsylvania stream. For an hour, I presented perfect drifts with a close-enough pattern (a Parachute Adams two sizes too small) without a single take. After switching to a proper extended-body drake imitation, I hooked fish on three consecutive casts with no change in presentation. Sometimes, the fly really does matter.

That said, I’ve watched extraordinary anglers catch fish on purposely “wrong” flies through sheer presentation mastery. My friend Mike, a guide on the Pere Marquette, once bet me he could catch a trout on a garish pink streamer during a delicate Blue-Winged Olive hatch. His perfect cast to a difficult lie under a fallen cedar resulted in an immediate strike from a 16-inch brown. The lesson? Master presentation first, then worry about having the perfect fly.

FAQ About Fly Fishing Food Sources

What’s the single most important fly pattern for a beginner to learn?

If I could only fish one pattern forever, it would be a Parachute Adams in sizes 14-18. It reasonably imitates most mayflies, can pass for a caddis in a pinch, and has a visible white post that helps track it on the water. I’ve caught trout on this fly in virtually every trout stream I’ve fished across North America.

How many fly patterns do you really need?

While my vests contain hundreds of patterns, I probably catch 80% of my fish on about a dozen flies. A thoughtfully selected dozen flies covering the major food sources will serve you better than hundreds of rarely-used specialty patterns. That said, having size variations is crucial – I carry my confidence patterns in at least 3 different sizes.

Are realistic flies worth the extra cost?

Sometimes, yes. Particularly during technical dry fly situations on heavily pressured waters, ultra-realistic patterns like comparaduns and CDC emergers can make a difference. However, for most situations, suggestive patterns that capture the key triggering features (size, silhouette, and color) will work just as well. I save my expensive realistic flies for those special situations when trout are being particularly selective.

What about attractor patterns that don’t imitate specific foods?

Attractor patterns like Royal Wulffs, Stimulators, and Purple Hazes don’t precisely match any natural food but can still be remarkably effective, especially in faster pocket water where trout have less time to inspect offerings. I always carry attractors as search patterns for exploring new water or when no obvious hatch is occurring. They’re particularly valuable when fishing with less experienced anglers who might struggle with drag-free presentations.

How do you know what size fly to use?

Size is often more important than exact pattern. When in doubt, I follow these guidelines:

- Try to match the size of visible naturals

- If no insects are visible, start with a #14-16 (a medium size that won’t spook wary fish but is still visible to the angler)

- In clear, low water conditions with pressured fish, size down

- In fast or turbid water, size up for visibility

When I first started fishing Michigan’s famous “Holy Waters” section of the Au Sable, I consistently used flies 2-4 sizes too large because that’s what I could easily see. Once I forced myself to fish more appropriate sizes (even when that meant straining to see my fly), my catch rates more than doubled.

Should you change flies frequently or stick with one pattern?

This is situational. When I’m confident fish are present but not taking my fly after multiple good drifts, I’ll change patterns. However, constantly changing flies can reduce your fishing time and confidence. I generally give a pattern 15-20 good drifts before changing unless I see a specific reason to switch sooner (like noticing a hatch I’d missed). Often, a small adjustment in presentation or position will produce strikes with the same fly you were about to change.

What’s the best way to determine what trout are feeding on?

The best indicator is always rising fish – observe the rise form, as different food sources create different rises. Lacking that:

- Seine the water with a small net to collect drifting insects

- Check spider webs near the water (they collect recently hatched insects)

- Look for exoskeletons (shucks) floating in foam lines or stuck to rocks

- Pump the stomach of the first fish caught (with a special tool that doesn’t harm the fish)

During one particularly tough day on the South Branch, I noticed tiny yellow specks in a spider web near the water. Upon closer inspection, they were miniature Yellow Sally stoneflies I’d completely overlooked. Switching to a small yellow stimulator immediately turned my day around.

Final Thoughts on Feeding Trout What They Want

Understanding what trout eat isn’t just about catching more fish – it connects you more deeply to the ecosystems we love to fish. I’ve found that my most satisfying days on the water often involve solving the puzzle of what trout are eating as much as the actual catching.

After three decades of observation, experimentation, and occasionally getting it spectacularly wrong (like the time I fished a giant hopper during what turned out to be a Trico spinner fall), I’ve learned that flexibility and observation trump preconceived notions every time. The best fly fishers I know aren’t those with the most expensive gear or even the best casting technique – they’re the ones who pay attention to what’s actually happening on the water and adjust accordingly.

Whether you’re just starting out or have been fly fishing for years, focusing on these seven fundamental food sources will dramatically improve your catch rates. Start with a representative selection covering each category, observe carefully, and let the trout tell you what they want. They’re the ultimate experts on their own feeding preferences, after all.

And remember, sometimes the “best” fly isn’t about catching the most fish, but about the experience that brings you the most joy. Some of my most memorable days involved targeting rising fish with tiny dry flies, even when a nymph might have caught more. There’s no wrong way to fly fish as long as you’re enjoying the process and respecting the resource.

Meet Adam Hawthorne

I’m a lifelong fishing enthusiast who’s spent years exploring rivers, lakes, and oceans with a rod in hand. At Fishing Titan, I share hands-on tips, honest gear reviews, and everything I’ve learned about fish and ocean life, so you can fish smarter and enjoy every cast.

Share:

Meet Adam Hawthorne

I’m a lifelong fishing enthusiast who’s spent years exploring rivers, lakes, and oceans with a rod in hand. At Fishing Titan, I share hands-on tips, honest gear reviews, and everything I’ve learned about fish and ocean life, so you can fish smarter and enjoy every cast.

Related Articles

-

Atlantic Salmon: Ultimate Guide for Anglers in 2025

For as long as I can remember, I’ve been captivated by Atlantic salmon fishing. There’s something almost mystical about these magnificent fish – their power,…

-

Why Stoner Fish Catch is Different: Unusual Angling Tactics

Let’s face it – some fish just act plain weird. Whether you’re an experienced angler or just starting out, you’ve probably encountered fish that seem…

-

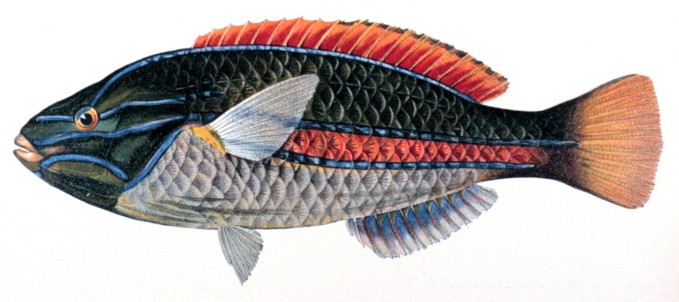

Molly Fish

The Molly Fish represents one of the most adaptable and ecologically significant freshwater species in tropical and subtropical regions worldwide. Known scientifically as *Poecilia sphenops*…

-

Fly Fishing in the UK: Top Rivers and Seasonal Patterns

After nearly three decades casting flies across waters from Michigan to Maine – and now spending several weeks each year exploring the UK’s rivers –…

Fish Species

-

Blue Platy

The Blue Platy (Xiphophorus maculatus) stands as one of the most recognizable and culturally significant freshwater fish species in the aquarium trade. This small, vibrant…

-

Rainbowfish

Rainbowfish represent one of the most visually striking and ecologically significant groups of freshwater fish found across Australia, New Guinea, and Indonesia. These vibrant schooling…

-

Discus Fish

The Discus Fish (Symphysodon spp.) stands as one of the most revered species in the freshwater aquarium trade, earning its reputation as the “King of…

-

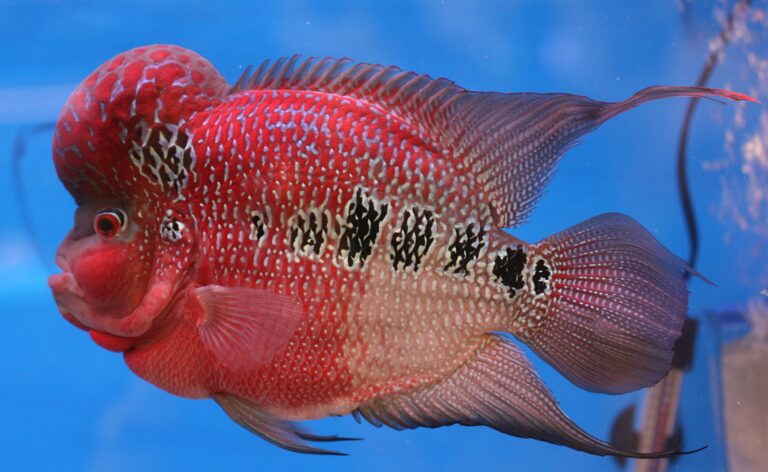

Flowerhorn Cichlid

The Flowerhorn Cichlid represents one of the most distinctive and culturally significant hybrid fish species in contemporary aquarium keeping. Created through selective breeding programs beginning…