Whale Shark

By Ryan Maron | Last Modified: July 12, 2025

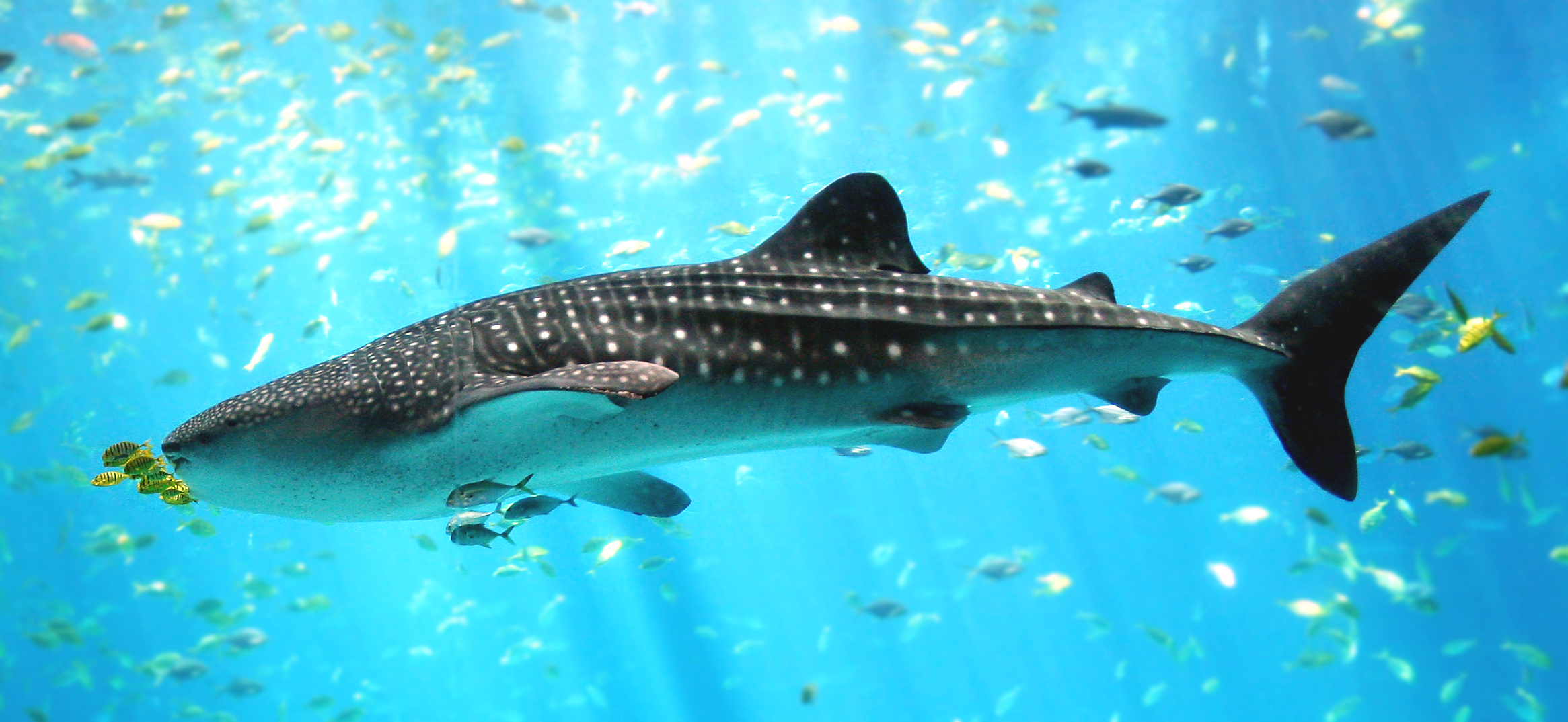

The whale shark (*Rhincodon typus*) stands as the ocean’s largest fish species, representing one of nature’s most remarkable gentle giants. Despite its imposing size, reaching lengths of up to 18 meters and weighing as much as 34 tonnes, this magnificent creature poses no threat to humans, feeding exclusively on microscopic plankton and small fish. The whale shark plays a crucial ecological role as a filter-feeding apex species, helping maintain the delicate balance of marine ecosystems across tropical and warm-temperate waters worldwide.

As the sole member of the family Rhincodontidae, the whale shark occupies a unique position in marine biodiversity. Its massive size and distinctive spotted pattern make it one of the most recognizable fish species in the ocean, while its gentle nature and slow-moving behavior have made it a flagship species for marine conservation efforts. The species serves as both a critical component of pelagic food webs and an important indicator of ocean health, making its study essential for understanding broader marine ecosystem dynamics.

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Common Name | Whale Shark |

| Scientific Name | Rhincodon typus |

| Family | Rhincodontidae |

| Typical Size | 4-12 meters (13-39 feet), up to 34 tonnes |

| Habitat | Tropical and warm-temperate pelagic waters |

| Diet | Planktonic filter feeder |

| Distribution | Circumtropical waters worldwide |

| Conservation Status | Endangered (IUCN Red List) |

Taxonomy & Classification

The whale shark belongs to the class Chondrichthyes, which encompasses all cartilaginous fishes including sharks, rays, and skates. Within this class, it falls under the subclass Elasmobranchii and the order Orectolobiformes, commonly known as carpet sharks. The species represents the sole member of the family Rhincodontidae, making it taxonomically unique among modern shark species.

First scientifically described by Andrew Smith in 1828, the whale shark was initially classified based on a specimen harpooned off the coast of South Africa. The genus name Rhincodon derives from the Greek words “rhinkhos” meaning snout and “odous” meaning tooth, referring to the species’ distinctive broad, flattened head and numerous small teeth. The specific epithet typus indicates that this species serves as the type specimen for its genus.

Molecular phylogenetic studies have revealed that whale sharks are most closely related to zebra sharks (Stegostoma fasciatum) and nurse sharks within the Orectolobiformes order. Despite their common name suggesting a relationship with whales, these fish are true sharks that have evolved convergent filter-feeding adaptations similar to baleen whales. The species shows no significant genetic variation across its global range, suggesting high gene flow between populations and relatively recent evolutionary divergence.

Recent taxonomic research has confirmed that all whale shark populations worldwide belong to a single species, *Rhincodon typus*, with no recognized subspecies. This taxonomic stability reflects the species’ highly migratory nature and the lack of geographic barriers in the open ocean environment that might lead to population differentiation.

Physical Description

The whale shark exhibits a distinctive fusiform body shape optimized for efficient swimming through open water. Adult specimens typically measure between 4 and 12 meters in length, though exceptional individuals can reach up to 18 meters. The species displays significant sexual dimorphism, with mature males generally smaller than females and possessing modified pelvic fins called claspers used for reproduction.

The whale shark’s most recognizable feature is its unique coloration pattern consisting of white spots and stripes against a dark blue-gray background. This checkerboard pattern is unique to each individual, serving as a natural identification system for researchers studying wild populations. The dorsal surface displays prominent ridges running longitudinally along the body, while the ventral surface remains predominantly white.

The head of a whale shark is broad and flattened, with a terminal mouth that can span up to 1.5 meters in width. The mouth contains over 3,000 minute teeth arranged in more than 300 rows, though these teeth play no role in feeding. Instead, the species relies on specialized gill rakers and filter pads to strain food particles from the water. The eyes are positioned laterally on the head and are relatively small compared to the animal’s overall size.

Five pairs of gill slits are located on the sides of the head, with the first pair being notably larger than the others. The whale shark possesses two dorsal fins, with the first being significantly larger and positioned roughly at the body’s midpoint. The caudal fin is heterocercal, meaning the upper lobe is longer than the lower lobe, which is characteristic of most shark species. The skin texture is rough due to the presence of dermal denticles, and the skin thickness can exceed 10 centimeters in some areas, providing protection from parasites and potential predators.

Habitat & Distribution

Whale sharks inhabit tropical and warm-temperate waters worldwide, typically found in areas where water temperatures remain above 21°C (70°F). The species demonstrates a preference for surface waters, commonly observed within the upper 200 meters of the water column, though individuals have been recorded diving to depths exceeding 1,000 meters. This vertical migration behavior appears to be related to feeding opportunities and thermoregulation.

The global distribution of whale sharks spans circumtropical waters, with documented populations in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans. Major aggregation sites include the waters off Western Australia, the Maldives, the Philippines, Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, and the Red Sea. These aggregation areas typically coincide with seasonal plankton blooms, coral spawning events, or upwelling zones that concentrate prey organisms.

Whale sharks exhibit highly migratory behavior, with satellite tagging studies revealing movement patterns covering thousands of kilometers. Adult females, in particular, demonstrate extensive migrations that may be linked to reproductive cycles and feeding opportunities. The species shows a preference for areas with high primary productivity, including continental shelf edges, seamounts, and regions influenced by upwelling currents.

Seasonal movements of whale sharks are closely tied to oceanographic conditions and prey availability. In many regions, their presence coincides with specific times of year when planktonic organisms are most abundant. For example, in the waters around Ningaloo Reef in Western Australia, whale sharks aggregate annually between March and July, coinciding with coral spawning events that provide rich feeding opportunities.

The species’ habitat preferences also include areas near coral reefs, particularly during spawning seasons when coral gametes provide concentrated nutrition. However, whale sharks are not reef-dependent and spend significant time in open ocean environments, following prey concentrations and temperature gradients that optimize their feeding efficiency.

Diet & Feeding Behavior

Whale sharks are obligate filter feeders, specializing in the consumption of planktonic organisms and small schooling fish. Their diet consists primarily of copepods, krill, fish eggs, small nektonic organisms, and occasionally small fish such as sardines and anchovies. The species exhibits remarkable feeding efficiency, capable of processing over 6,000 cubic meters of water per hour through their specialized filtration system.

The feeding mechanism involves two primary strategies: passive feeding and active feeding. During passive feeding, whale sharks swim slowly with their mouths open, allowing water to flow through their oral cavity and over their gill rakers. Active feeding involves more dynamic behavior, including vertical feeding postures where the shark positions itself head-up near the surface, creating suction to draw in prey-rich water.

Feeding aggregations of whale sharks often occur in response to ephemeral prey concentrations, such as fish spawning events or plankton blooms. These aggregations can include multiple individuals feeding in close proximity, though direct competition appears minimal due to the abundance of available prey during these events. The species demonstrates remarkable ability to locate and exploit these temporary food sources across vast oceanic distances.

The filtration apparatus consists of specialized gill rakers and filtering pads that trap particles as small as 2-3 millimeters. Water enters through the mouth and exits through the gill slits, while prey items are retained and subsequently swallowed. This feeding strategy is remarkably similar to that employed by baleen whales, representing an excellent example of convergent evolution in marine filter feeders.

Whale sharks show feeding preferences that vary by location and season. In some areas, they focus primarily on copepods and other small crustaceans, while in others, they may target fish eggs during spawning seasons. The species’ feeding behavior is closely linked to lunar cycles, tidal patterns, and seasonal oceanographic conditions that influence prey distribution and abundance.

Behavior & Adaptations

Whale sharks exhibit a range of behavioral adaptations that reflect their specialized ecological niche as large pelagic filter feeders. The species is generally solitary, though individuals may aggregate in areas of high prey density. Social interactions are typically limited to feeding aggregations and mating behavior, with no evidence of complex social structures or cooperative behaviors.

Swimming behavior is characterized by a slow, steady pace averaging 3-5 kilometers per hour, though individuals can achieve burst speeds of up to 17 kilometers per hour when necessary. The species demonstrates remarkable diving abilities, with recorded depths exceeding 1,900 meters. These deep dives may serve multiple functions, including thermoregulation, predator avoidance, and accessing deep-water prey organisms.

Thermoregulatory behavior is particularly important for whale sharks, as they must maintain optimal body temperature while moving between different water masses. The species exhibits behavioral thermoregulation by adjusting their vertical position in the water column, often basking near the surface during cooler periods and diving to deeper waters during warmer parts of the day.

The whale shark’s gentle nature and tolerance of human presence has made it a popular species for ecotourism activities. However, this behavior may also make the species vulnerable to human-induced threats, as individuals often fail to exhibit avoidance responses to boats and other potential hazards. Research suggests that whale sharks may use magnetic fields and other environmental cues for navigation during long-distance migrations.

Cleaning behavior is commonly observed, with whale sharks allowing small fish species to remove parasites and dead skin from their bodies. This mutualistic relationship benefits both the whale shark and the cleaner fish, and cleaning stations are often established at specific locations where whale sharks regularly visit.

Reproduction & Life Cycle

Whale shark reproduction remains one of the least understood aspects of their biology, largely due to the species’ oceanic lifestyle and the difficulty of observing mating behavior in the wild. The species is ovoviviparous, meaning that eggs develop inside the female’s body and young are born as miniature versions of adults. This reproductive strategy is relatively uncommon among shark species and contributes to the whale shark’s slow reproductive rate.

Sexual maturity in whale sharks is reached at an estimated age of 20-25 years, with females typically maturing at larger sizes than males. Mature females may reach lengths of 8-10 meters, while males typically mature at 4-6 meters. The extended period to sexual maturity makes the species particularly vulnerable to population decline, as individuals must survive for decades before contributing to reproduction.

Gestation periods are estimated to be 12-14 months, though this remains uncertain due to limited observations of pregnant females. The largest documented litter contained 300 embryos in various stages of development, suggesting that females may mate with multiple males and store sperm for extended periods. Young whale sharks are born at approximately 55-70 centimeters in length and are immediately independent.

Nursery areas for juvenile whale sharks remain largely unknown, though smaller individuals are occasionally observed in shallow coastal waters. This size-based habitat segregation may serve to reduce competition with adults and provide protection from larger predators. The species’ slow growth rate means that individuals may take several decades to reach their full size potential.

Mating behavior has rarely been observed in the wild, though aggregations of adult individuals in certain locations may represent breeding areas. The species’ highly migratory nature suggests that mating may occur in specific geographic regions or during particular seasons, possibly linked to oceanographic conditions that support high prey concentrations.

Predators & Threats

Adult whale sharks have few natural predators due to their enormous size, though juveniles and smaller individuals may be vulnerable to larger sharks, including great white sharks and tiger sharks. Killer whales (Orcinus orca) have been documented attacking whale sharks in some regions, though such predation events appear to be relatively rare. The species’ thick skin and large size provide significant protection against most potential predators.

Human activities represent the most significant threat to whale shark populations worldwide. Ship strikes pose a major risk, as the species’ surface-oriented behavior and slow swimming speed make collision avoidance difficult. The increasing volume of maritime traffic in whale shark habitats has led to documented mortality from vessel strikes, particularly in areas where shipping lanes intersect with aggregation sites.

Fishing pressure, both direct and indirect, significantly impacts whale shark populations. While targeted fishing for whale sharks has been prohibited in many countries, individuals are still caught as bycatch in commercial fishing operations. Gillnets, purse seines, and longlines all pose risks to whale sharks, with entanglement often resulting in mortality due to the species’ inability to break free from fishing gear.

Climate change presents emerging threats to whale shark populations through alterations in ocean temperature, currents, and prey distribution. Changes in sea surface temperature may affect the timing and location of plankton blooms, potentially disrupting the species’ feeding patterns and migration routes. Ocean acidification may also impact the abundance of prey organisms, particularly small crustaceans that form a significant portion of the whale shark’s diet.

Pollution, including plastic debris and chemical contaminants, poses additional risks to whale shark populations. The species’ filter-feeding behavior makes them particularly vulnerable to ingesting microplastics and other pollutants that accumulate in marine food webs. Heavy metals and persistent organic pollutants have been detected in whale shark tissues, though the long-term effects of these contaminants remain poorly understood.

Conservation Status

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classifies the whale shark as Endangered on the Red List of Threatened Species, reflecting significant population declines observed across much of the species’ range. Population assessments indicate that global whale shark numbers have declined by more than 50% over the past 75 years, with some regional populations experiencing even steeper declines.

The species is listed under Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), which regulates international trade in whale shark products. This listing has helped reduce commercial exploitation, though enforcement remains challenging in some regions. The Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species (CMS) also lists whale sharks under Appendix I and II, recognizing the need for international cooperation in conservation efforts.

Regional conservation initiatives have been established in many areas where whale sharks aggregate, including the creation of marine protected areas and the implementation of tourism management guidelines. Countries such as Australia, Mexico, and the Philippines have implemented comprehensive protection measures, including prohibitions on fishing and strict regulations for tourism activities.

Research efforts have intensified in recent years, with scientists using satellite tagging, genetic analysis, and photo-identification techniques to better understand whale shark ecology and population dynamics. These studies have revealed important information about migration patterns, habitat requirements, and population connectivity that is essential for developing effective conservation strategies.

The species’ slow growth rate, late sexual maturity, and low reproductive output make population recovery challenging even with complete protection. Conservation efforts must therefore focus on reducing human-induced mortality while protecting critical habitats and migration corridors. International cooperation is essential given the species’ highly migratory nature and the transboundary nature of many threats.

Human Interaction

Whale sharks have developed a unique relationship with humans, becoming one of the most sought-after species for marine wildlife tourism. Their docile nature and surface-oriented behavior make them ideal subjects for swimming and diving encounters, generating significant economic value in many coastal communities. Countries such as Australia, Mexico, the Maldives, and the Philippines have developed substantial ecotourism industries based on whale shark encounters.

The economic value of whale shark tourism often exceeds the value of traditional fishing activities, providing strong incentives for conservation. Studies have estimated that a single whale shark can generate millions of dollars in tourism revenue over its lifetime, far exceeding the one-time value of the animal if killed. This economic argument has proven effective in gaining support for conservation measures in many regions.

However, unregulated tourism can pose risks to whale shark populations. Physical contact, overcrowding, and harassment by swimmers and boats can stress individuals and potentially alter their behavior. Many countries have implemented tourism guidelines that specify minimum distances, group sizes, and interaction protocols to minimize impacts on whale sharks while maintaining viable tourism opportunities.

Traditional fishing communities have historically utilized whale sharks for food, oil, and other products, though this practice has declined significantly due to conservation measures and changing economic opportunities. In some regions, former whale shark hunters have transitioned to roles as guides and conservationists, bringing valuable local knowledge to research and tourism activities.

Scientific research on whale sharks has benefited greatly from citizen science initiatives, with tourists and dive operators contributing photographs and sighting data that help researchers track individual animals and monitor population trends. These collaborative efforts have significantly expanded the spatial and temporal scope of whale shark research while engaging the public in conservation activities.

The species’ charismatic nature has made it an effective flagship species for marine conservation, helping to raise awareness about broader ocean conservation issues. Whale sharks appear prominently in educational materials, media productions, and conservation campaigns, serving as ambassadors for the protection of marine ecosystems worldwide.

Interesting Facts

Whale sharks possess the largest brain of any fish species, though their brain-to-body weight ratio is relatively small compared to other vertebrates. Despite their massive size, whale sharks can live for over 100 years, with some estimates suggesting maximum lifespans of 130 years or more. Growth rates are extremely slow, with individuals gaining only 20-30 centimeters per year during their juvenile stages.

The species exhibits remarkable diving abilities, with recorded depths exceeding 1,900 meters. These deep dives may serve multiple purposes, including accessing deep-water prey, thermoregulation, and potentially avoiding surface disturbances. Whale sharks can remain submerged for extended periods, with documented dive durations exceeding 17 hours.

Each whale shark’s spot pattern is unique, functioning like a fingerprint for individual identification. Researchers have developed sophisticated algorithms to match spot patterns from photographs, enabling long-term studies of individual animals. Some individuals have been tracked for over 20 years, providing valuable insights into their behavior and longevity.

The species demonstrates remarkable navigation abilities, with satellite tracking revealing precise return visits to specific locations separated by thousands of kilometers. This suggests sophisticated spatial memory and navigation systems that may rely on magnetic fields, water chemistry, or other environmental cues. Some whale sharks have been documented following the same migration routes year after year with remarkable precision.

Whale sharks can process enormous volumes of water through their filtration system, with estimates suggesting they can filter up to 6,000 cubic meters of water per hour. This remarkable efficiency allows them to extract sufficient nutrition from relatively dilute prey concentrations in open ocean environments. The species’ feeding success is closely linked to their ability to locate and exploit ephemeral prey aggregations across vast oceanic distances.

Despite their massive size, whale sharks are remarkably buoyant, with their large liver containing high concentrations of oils that provide near-neutral buoyancy. This adaptation allows them to maintain their position in the water column with minimal energy expenditure, an important consideration for an animal that must filter enormous volumes of water to meet its nutritional needs.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are whale sharks dangerous to humans?

Whale sharks pose no danger to humans despite their enormous size. They are filter feeders that consume only plankton and small fish, and their gentle nature makes them popular subjects for swimming and diving encounters. However, their size means that accidental contact could potentially cause injury, so maintaining appropriate distances during encounters is important for both human safety and animal welfare.

How big do whale sharks get?

Whale sharks typically reach lengths of 4-12 meters (13-39 feet), though exceptional individuals can grow up to 18 meters (59 feet) in length. They can weigh as much as 34 tonnes, making them the largest fish species in the world. Females generally grow larger than males, with mature females often exceeding 8-10 meters in length.

Where can you swim with whale sharks?

Popular destinations for whale shark encounters include Western Australia (Ningaloo Reef), Mexico (Isla Holbox and La Paz), the Maldives, the Philippines (Donsol and Oslob), and the Red Sea. These locations offer seasonal aggregations where whale sharks can be observed reliably, though timing varies by location and is typically linked to plankton blooms or fish spawning events.

How long do whale sharks live?

Whale sharks are extremely long-lived, with recent studies suggesting lifespans exceeding 100 years. Some estimates indicate maximum ages of 130 years or more, making them among the longest-living vertebrates. Their slow growth rate and late sexual maturity contribute to their longevity but also make them vulnerable to population declines.

Conclusion

The whale shark represents one of the ocean’s most remarkable species, combining massive size with gentle feeding behavior and complex ecological relationships. As the world’s largest fish, it serves as both a crucial component of marine ecosystems and a flagship species for ocean conservation. However, its endangered status reflects the significant challenges facing marine megafauna in an increasingly human-dominated world. Continued research, international cooperation, and sustainable management of human interactions will be essential for ensuring the long-term survival of these magnificent gentle giants.

Share The Article:

More Fish Species:

-

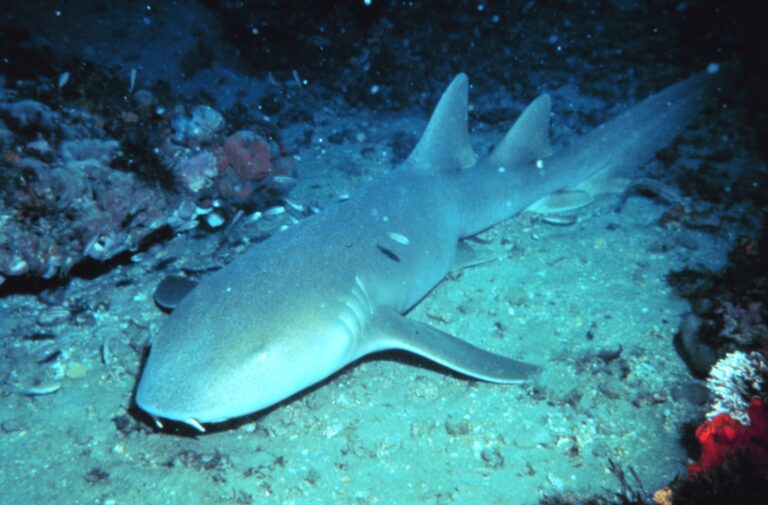

Nurse Shark

The Nurse Shark (Ginglymostoma cirratum) stands as one of the most recognizable and ecologically significant bottom-dwelling sharks in tropical…

-

Tuxedo Platy

The Tuxedo Platy (Xiphophorus maculatus) stands as one of the most recognizable and beloved freshwater aquarium fish species, distinguished…

-

Red Belly Piranha

The Red Belly Piranha (*Pygocentrus nattereri*) stands as one of South America’s most misunderstood freshwater predators, wielding razor-sharp teeth…

-

Madtom Catfish

The Madtom Catfish represents one of North America’s most fascinating yet underappreciated groups of freshwater fish. These diminutive members…

-

Gold Gourami

The Gold Gourami (Trichopodus trichopterus) represents one of Southeast Asia’s most recognizable freshwater fish species, distinguished by its robust…

-

Paradise Fish

The Paradise Fish stands as one of the most remarkable representatives of the labyrinth fish family, captivating aquarists and…

Discover

-

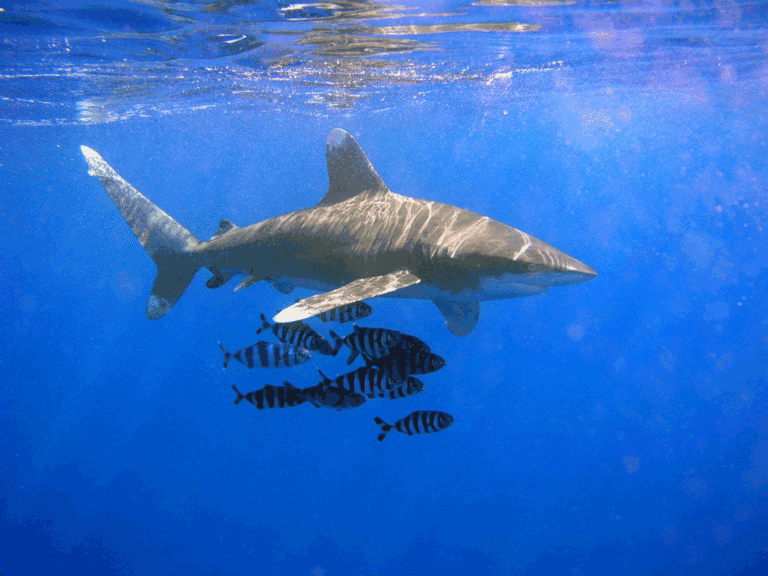

Oceanic Whitetip Shark

The Oceanic Whitetip Shark (*Carcharhinus longimanus*) stands as one of the ocean’s most formidable and recognizable apex predators, distinguished…

-

North Jersey Fishing Guide: Best Lakes, Rivers & Seasons

If you’ve never experienced the fishing in North Jersey, you’re missing out on some genuinely underrated angling opportunities. From…

-

Best Fishing Spots in California: Lakes, Rivers, and Coastal Hotspots

California fishing has always struck me as a study in beautiful contradictions. From snow-fed alpine lakes to sweltering desert…

-

Pelagic Thresher Shark

The Pelagic Thresher Shark stands as one of the ocean’s most distinctive and efficient predators, renowned for its dramatically…

-

How to Find Good Fishing Spots That Actually Produce Fish

Finding productive fishing spots is often what separates successful anglers from those who go home empty-handed. It’s not just…

-

How to Fish for Salmon in 2025: Expert Tips and Techniques

Few fishing experiences match the thrill of feeling a salmon take your line. These powerful fish have captivated anglers…

Discover

-

Porbeagle Shark

The Porbeagle Shark (*Lamna nasus*) stands as one of the most fascinating and ecologically significant predators in the North…

-

Bora Bora Fishing: What I Learned After 3 Failed Trips

I still remember staring at those impossibly blue waters on my first morning in Bora Bora, thinking I was…

-

Guppy

The Guppy (Poecilia reticulata) stands as one of the most recognizable and extensively studied freshwater fish species in the…

-

Atlantic Salmon: Ultimate Guide for Anglers in 2025

For as long as I can remember, I’ve been captivated by Atlantic salmon fishing. There’s something almost mystical about…

-

European Pike Fishing: Top Techniques for Northern Pike

I still remember my first encounter with European pike fishing methods. It was during a trip to Sweden about…

-

Kayak Fishing vs Boat Fishing: Which Truly Offers the Best Experience?

There’s nothing quite like the debate that erupts when you ask a group of anglers whether kayak fishing or…