Spinner Shark

By Ryan Maron | Last Modified: July 7, 2025

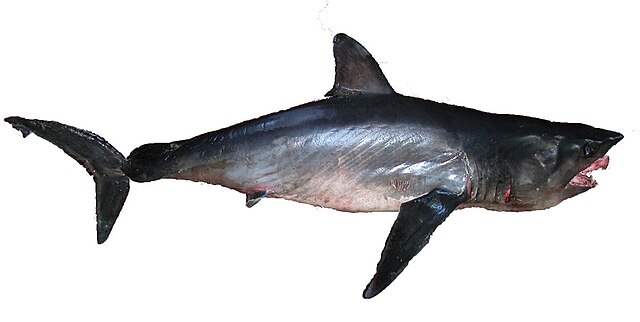

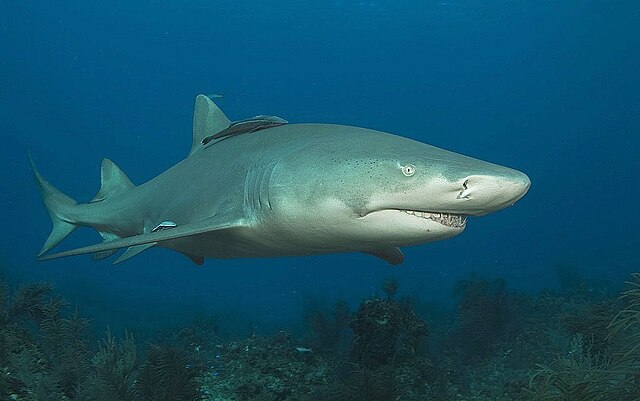

The Spinner Shark (Carcharhinus brevipinna) stands as one of the ocean’s most distinctive and acrobatic predators, earning its name from the spectacular spinning leaps it performs when hooked or feeding. This medium-sized requiem shark inhabits warm coastal waters across the globe, playing a crucial role as an apex predator in marine ecosystems. The species demonstrates remarkable adaptability, thriving in both nearshore and offshore environments while maintaining complex migratory patterns that span thousands of miles. As both a commercially valuable species and an indicator of ocean health, the Spinner Shark represents the delicate balance between human exploitation and marine conservation efforts.

| Feature | Details |

| Common Name | Spinner Shark |

| Scientific Name | Carcharhinus brevipinna |

| Family | Carcharhinidae |

| Typical Size | 200-250 cm (6.5-8.2 ft), 56-90 kg |

| Habitat | Warm coastal and offshore waters |

| Diet | Small schooling fish, cephalopods |

| Distribution | Tropical and subtropical waters worldwide |

| Conservation Status | Near Threatened (IUCN) |

Taxonomy & Classification

The Spinner Shark belongs to the family Carcharhinidae, commonly known as requiem sharks, which represents the largest family of sharks with over 60 species. Valentini first described Carcharhinus brevipinna in 1822, though the species underwent several taxonomic revisions before achieving its current classification. The genus name Carcharhinus derives from the Greek words “karcharos” meaning sharp and “rhinos” meaning nose, while the species epithet “brevipinna” translates to “short fin” in Latin, referring to the relatively short pectoral fins compared to similar species.

Within the Carcharhinidae family, the Spinner Shark shares close evolutionary relationships with other members of the Carcharhinus genus, particularly the Bull Shark and Blacktip Shark. Molecular phylogenetic studies indicate that these species diverged approximately 15-20 million years ago during the Miocene epoch. The taxonomic classification places the Spinner Shark within the broader evolutionary context of carcharhiniform sharks, which evolved specialized hunting strategies and reproductive mechanisms that distinguish them from other shark orders.

Recent genetic analyses have revealed subtle population variations across different ocean basins, leading some researchers to propose potential subspecies designations. However, the current taxonomic consensus maintains Carcharhinus brevipinna as a single species with distinct regional populations rather than separate subspecies. This classification reflects the species’ remarkable ability to maintain genetic connectivity across vast oceanic distances through long-distance migrations and occasional interbreeding between populations.

Physical Description

The Spinner Shark exhibits a streamlined, fusiform body shape optimized for efficient swimming and rapid acceleration during feeding pursuits. Adult specimens typically reach lengths of 200-250 centimeters, with exceptional individuals exceeding 280 centimeters in length. The species displays pronounced sexual dimorphism, with females generally growing larger than males and reaching greater maximum sizes. The body coloration consists of a bronze to gray-brown dorsal surface that gradually transitions to a white ventral surface, providing effective countershading for camouflage in open water environments.

The distinctive features of the Spinner Shark include a moderately long, pointed snout and relatively small eyes positioned laterally on the head. The mouth contains 15-16 tooth rows in the upper jaw and 14-15 rows in the lower jaw, with each tooth displaying a narrow, triangular shape and serrated edges adapted for grasping and cutting prey. The first dorsal fin originates above the posterior margin of the pectoral fins and features a distinctive black tip that becomes more pronounced with age. The pectoral fins appear proportionally smaller than those of closely related species, contributing to the species’ taxonomic designation.

The caudal fin exhibits the typical heterocercal structure of sharks, with the upper lobe significantly longer than the lower lobe, providing propulsion efficiency during sustained swimming. The second dorsal fin and anal fin are positioned relatively close together, with the anal fin slightly anterior to the second dorsal fin. Juvenile Spinner Sharks often display more prominent fin markings, including black-tipped pectoral and dorsal fins, which may fade or become less distinct as the animals mature. The dermal denticles covering the skin are small and closely spaced, reducing drag and contributing to the species’ hydrodynamic efficiency.

Habitat & Distribution

Spinner Sharks inhabit warm temperate and tropical waters across the globe, demonstrating one of the most extensive distributions among requiem sharks. The species occurs in the western Atlantic from North Carolina to southern Brazil, including the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea. In the eastern Atlantic, populations extend from Morocco to Angola, encompassing the Mediterranean Sea where they represent a relatively rare but documented presence. Indo-Pacific populations range from the Red Sea and East Africa to southern Japan, Australia, and the central Pacific islands.

The preferred habitat of Spinner Sharks encompasses both nearshore and offshore pelagic environments, with individuals regularly encountered from the surf zone to depths exceeding 100 meters. These sharks demonstrate a strong affinity for continental shelf waters, particularly areas with upwelling currents that concentrate prey species. Coastal aggregations frequently occur near drop-offs, seamounts, and areas where warm and cold water masses converge, creating productive feeding zones with high prey density.

Seasonal migration patterns characterize Spinner Shark populations in many regions, with individuals moving between feeding and breeding areas in response to water temperature changes and prey availability. In the western Atlantic, tagging studies have documented migrations exceeding 2,000 kilometers, with sharks moving northward during summer months and returning to warmer waters during winter. These movements often coincide with the seasonal migrations of preferred prey species, including sardines, anchovies, and mackerel. The species shows remarkable site fidelity to specific nursery areas, with pregnant females returning to the same coastal regions for pupping across multiple reproductive cycles.

Diet & Feeding Behavior

The Spinner Shark functions as an opportunistic predator specializing in small to medium-sized schooling fish and cephalopods. The primary prey species include sardines, anchovies, herrings, mackerel, and bluefish, with cephalopods such as squid comprising a significant portion of the diet in offshore environments. Stomach content analyses reveal that prey selection varies seasonally and geographically, reflecting the opportunistic nature of the species and its ability to exploit locally abundant food sources.

The feeding behavior of Spinner Sharks incorporates both individual and group hunting strategies, with the species demonstrating remarkable coordination during feeding frenzies. The characteristic spinning behavior occurs when sharks charge vertically through schools of prey fish, rotating their bodies as they breach the surface while maintaining their grip on captured prey. This acrobatic feeding technique serves multiple purposes, including disorienting prey schools and maximizing capture efficiency during brief feeding opportunities.

Feeding activity typically peaks during dawn and dusk periods, corresponding with the vertical migrations of prey species and reduced light conditions that favor ambush predation. The species exhibits seasonal feeding patterns, with increased activity during summer months when prey abundance reaches peak levels in many regions. Young Spinner Sharks demonstrate different feeding preferences compared to adults, focusing primarily on smaller fish species and crustaceans in shallow nearshore environments. This ontogenetic shift in diet reduces intraspecific competition and allows different age classes to exploit distinct ecological niches within the same general habitat range.

Behavior & Adaptations

Spinner Sharks exhibit complex behavioral adaptations that enable successful survival in diverse marine environments. The species demonstrates strong schooling behavior, particularly during feeding activities and seasonal migrations, with aggregations sometimes numbering in the hundreds of individuals. These schools often consist of similarly sized individuals, suggesting that size-based social organization reduces competition and improves feeding efficiency. The sharks maintain specific spatial relationships within schools, with dominant individuals typically occupying central positions that provide optimal access to prey resources.

The iconic spinning behavior that gives the species its common name represents a highly specialized feeding adaptation. During vertical feeding rushes, Spinner Sharks can achieve rotational speeds exceeding 360 degrees per second while maintaining precise control over their trajectory and prey capture. This behavior requires exceptional neuromuscular coordination and demonstrates the species’ evolutionary refinement of feeding techniques. The spinning motion also serves as a mechanism for removing parasites and may play a role in social communication within feeding aggregations.

Thermoregulatory adaptations allow Spinner Sharks to maintain optimal body temperatures across different water masses and depths. The species exhibits counter-current heat exchange in blood vessels supplying the brain and eyes, enabling enhanced sensory performance in cooler waters. This physiological adaptation supports the species’ ability to exploit temperature gradients and follow prey migrations across different thermal environments. Spinner Sharks also demonstrate remarkable navigational abilities, utilizing geomagnetic cues and celestial navigation to maintain course during long-distance migrations spanning thousands of kilometers.

Reproduction & Life Cycle

Spinner Sharks follow a viviparous reproductive strategy with a yolk-sac placental connection, typical of many requiem shark species. Sexual maturity occurs at approximately 170-200 centimeters in length for both sexes, corresponding to an age of 7-10 years based on vertebral aging studies. The reproductive cycle follows a biennial pattern in most populations, with females producing litters every two years following a gestation period of approximately 11-12 months.

Mating behavior involves complex courtship rituals that occur in specific geographic areas during late spring and early summer months. Males exhibit competitive behaviors including parallel swimming, circling, and gentle biting of potential mates. The actual mating process involves the male grasping the female’s pectoral fin with his teeth while inserting one clasper for sperm transfer. Following successful mating, embryonic development occurs over nearly a year, with the developing young initially sustained by yolk reserves before establishing placental connections for nutrient transfer.

Litter sizes typically range from 3-15 pups, with an average of 7-8 offspring per reproductive cycle. Neonates measure 60-75 centimeters at birth and are immediately independent, receiving no parental care following birth. Nursery areas are typically located in shallow coastal waters that provide protection from larger predators and abundant prey resources for juvenile growth. The species demonstrates remarkable site fidelity to nursery areas, with pregnant females returning to the same coastal regions across multiple reproductive cycles. Juvenile growth rates average 15-20 centimeters per year during the first several years of life, gradually decreasing as the animals approach sexual maturity.

Predators & Threats

Adult Spinner Sharks face predation primarily from larger shark species, including Tiger Sharks, Great White Sharks, and occasionally large Bull Sharks in overlapping habitat areas. Juvenile Spinner Sharks experience higher predation pressure from a broader range of species, including other carcharhinid sharks, large groupers, and barracuda. The species’ fast swimming ability and schooling behavior serve as primary defense mechanisms against potential predators, with individuals capable of reaching burst speeds exceeding 35 kilometers per hour.

Commercial and recreational fishing represent the most significant anthropogenic threats to Spinner Shark populations worldwide. The species is targeted in directed fisheries for its meat, fins, and liver oil, while also being captured as bycatch in fisheries targeting other species. Longline fisheries pose particular risks due to the species’ tendency to take baited hooks, while gillnet fisheries in coastal areas impact both adult and juvenile populations. The relatively slow growth rate and late sexual maturity of the species make populations particularly vulnerable to overexploitation.

Habitat degradation and climate change present emerging threats to Spinner Shark populations, particularly in coastal nursery areas where human development impacts water quality and prey availability. Ocean warming and acidification may alter prey distributions and affect the species’ migration patterns, potentially disrupting established breeding and feeding cycles. Pollution, including plastic debris and chemical contaminants, bioaccumulates in shark tissues and may impact reproductive success and immune function. Coastal development and water quality degradation in nursery areas pose additional risks to juvenile survival and recruitment to adult populations.

Conservation Status

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) currently classifies the Spinner Shark as Near Threatened globally, reflecting declining population trends in several regions due to fishing pressure and habitat degradation. Regional assessments indicate more severe population declines in heavily fished areas, with some populations experiencing reductions exceeding 50% over the past three decades. The species’ slow growth rate, late sexual maturity, and relatively small litter sizes make populations particularly vulnerable to overexploitation and slow to recover from population declines.

Management measures for Spinner Shark populations vary significantly across different regions and jurisdictions. The United States has implemented species-specific regulations under the Fishery Management Plan for Atlantic Highly Migratory Species, including minimum size limits and annual catch quotas. The European Union has established fishing quotas for Mediterranean populations, while several countries have implemented seasonal closures in critical nursery areas. However, enforcement challenges and limited international coordination continue to hamper effective conservation efforts.

Research priorities for Spinner Shark conservation include improved population assessments, migration corridor mapping, and nursery area identification. Satellite tagging studies have provided valuable insights into movement patterns and habitat utilization, informing the development of spatially explicit management strategies. Genetic studies are revealing population structure and connectivity patterns that are essential for designing effective conservation units. International cooperation through organizations such as the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) and regional fisheries management organizations is crucial for implementing coordinated conservation measures across the species’ global range.

Human Interaction

Spinner Sharks have historically supported important commercial fisheries throughout their range, with landings primarily destined for human consumption and shark fin markets. In the United States, the species is managed under federal regulations that establish minimum size limits, possession limits, and seasonal closures to protect reproductive populations. The meat is marketed fresh and frozen, while the fins command high prices in international markets. Recreational fishing for Spinner Sharks has gained popularity in many coastal areas, with the species prized for its acrobatic fighting ability and the challenge of landing large specimens.

The species plays a significant role in marine ecotourism, particularly in areas where seasonal aggregations occur. Shark diving operations in locations such as South Africa, Florida, and the Bahamas provide opportunities for underwater encounters with Spinner Sharks, generating economic benefits for local communities while raising awareness about shark conservation. These ecotourism activities require careful management to minimize impacts on natural behaviors and avoid alterations to feeding and migration patterns.

Spinner Shark attacks on humans are extremely rare, with the species generally showing little interest in human activities. When encounters do occur, they are typically cases of mistaken identity in turbid water conditions or involve sharks attracted to fishing activities. The species’ preference for open water habitats and small prey species reduces the likelihood of aggressive interactions with humans. However, the acrobatic nature of hooked Spinner Sharks requires anglers to exercise caution during fishing activities, as the species’ jumping behavior can create dangerous situations for boat occupants.

Interesting Facts

The Spinner Shark holds the record for the most complete rotations achieved by any shark species during breaching behavior, with individuals capable of completing up to four full rotations while airborne. This remarkable acrobatic ability results from the species’ unique muscle fiber composition and specialized neural control mechanisms that enable precise coordination during high-speed feeding maneuvers. The spinning motion generates forces exceeding 4 G’s, requiring specialized physiological adaptations to maintain consciousness and spatial orientation.

Unlike many other shark species, Spinner Sharks exhibit remarkable temperature tolerance, with individuals documented in water temperatures ranging from 16°C to 32°C. This thermal adaptability enables the species to exploit a broader range of habitats and follow prey migrations across different temperature regimes. The species also demonstrates exceptional navigational abilities, with satellite tracking studies revealing that individuals can maintain straight-line courses across thousands of kilometers of open ocean, suggesting the use of sophisticated magnetic and celestial navigation systems.

Spinner Sharks possess one of the most acute electroreception systems among shark species, with the ability to detect electrical fields as weak as 0.005 microvolts per centimeter. This sensory capability enables the detection of prey muscle contractions and heartbeats at distances exceeding 30 centimeters, providing a significant advantage during feeding in turbid water conditions. The species also demonstrates remarkable memory capabilities, with individuals showing site fidelity to specific feeding areas and migration routes across multiple years, suggesting complex cognitive abilities and spatial memory systems.

Frequently Asked Questions

How dangerous are Spinner Sharks to humans?

Spinner Sharks pose minimal threat to humans, with very few documented attacks on record. The species typically avoids human contact and feeds primarily on small schooling fish rather than large prey. When encounters occur, they are usually cases of mistaken identity in murky water conditions or involve sharks attracted to fishing activities rather than aggressive behavior toward humans.

Why do Spinner Sharks spin out of the water?

The spinning behavior serves as a specialized feeding strategy that allows the sharks to maintain their grip on prey while breaking through the surface tension of dense fish schools. This acrobatic technique helps disorient prey and maximizes capture efficiency during brief feeding opportunities. The spinning motion may also help remove parasites and could play a role in social communication within feeding groups.

How can you distinguish a Spinner Shark from similar species?

Spinner Sharks can be identified by their bronze to gray-brown coloration, relatively small pectoral fins, and distinctive black-tipped dorsal and pectoral fins that become more prominent with age. The species has a moderately long, pointed snout and proportionally smaller eyes compared to similar requiem sharks. The characteristic spinning behavior during feeding activities provides another reliable identification marker.

Where are the best places to see Spinner Sharks?

Spinner Sharks are commonly encountered in warm coastal waters of the southeastern United States, Gulf of Mexico, and Caribbean Sea, particularly during summer months when they aggregate for feeding. Popular locations include the waters off Florida, Louisiana, and the Outer Banks of North Carolina. The species also occurs in the Indo-Pacific region, with notable populations around southern Africa and Australia.

Conclusion

The Spinner Shark represents a remarkable example of evolutionary adaptation to pelagic marine environments, combining specialized feeding behaviors with exceptional physical capabilities. As populations face increasing pressure from commercial fishing and habitat degradation, the species serves as an important indicator of ocean health and the effectiveness of marine conservation efforts. Understanding and protecting these magnificent predators ensures the continued functioning of marine ecosystems and maintains the biodiversity that supports both ecological balance and human livelihoods dependent on healthy ocean environments.

Share The Article:

More Fish Species:

-

Pleco

The **Pleco**, scientifically known as *Pterygoplichthys multiradiatus* (common pleco), represents one of the most recognizable and ecologically significant groups…

-

Balloon Molly

The Balloon Molly (*Poecilia latipinna* var.) represents one of the most distinctive and popular ornamental fish varieties in the…

-

Channel Catfish

The Channel Catfish stands as one of North America’s most recognizable and economically important freshwater fish species. Known scientifically…

-

Double Tail Betta

The Double Tail Betta, scientifically known as Betta splendens, represents one of the most distinctive and captivating variants within…

-

Variable Platyfish

The Variable Platyfish (Xiphophorus variatus) stands as one of the most widely recognized and ecologically significant freshwater fish species…

-

Gold Gourami

The Gold Gourami (Trichopodus trichopterus) represents one of Southeast Asia’s most recognizable freshwater fish species, distinguished by its robust…

Discover

-

Longfin Mako Shark

The Longfin Mako Shark represents one of nature’s most enigmatic and misunderstood predators, embodying both the raw power and…

-

Kayak Fishing vs Boat Fishing: Which Truly Offers the Best Experience?

There’s nothing quite like the debate that erupts when you ask a group of anglers whether kayak fishing or…

-

Pennsylvania Fishing License: Complete Guide for Anglers in 2025

Getting your Pennsylvania fishing license sorted isn’t exactly the most exciting part of fishing, but it’s absolutely necessary if…

-

Bora Bora Fishing: What I Learned After 3 Failed Trips

I still remember staring at those impossibly blue waters on my first morning in Bora Bora, thinking I was…

-

Great White Shark

The Great White Shark (*Carcharodon carcharias*) stands as one of the ocean’s most formidable apex predators, commanding respect and…

-

Types of Ocean Fishing: Complete Guide for Beginners

There’s something magical about standing at the edge of the vast ocean with a fishing rod in hand. I’ve…

Discover

-

East Coast Surf Fishing: Targeting Striped Bass and Bluefish from Shore

When I first tried East Coast surf fishing nearly 15 years ago, I was absolutely terrible at it. I…

-

Lemon Shark

The Lemon Shark (*Negaprion brevirostris*) represents one of the most scientifically studied and ecologically significant predators in coastal marine…

-

River Fishing Techniques: Master the Moving Water

Fishing rivers presents a unique set of challenges and rewards that I’ve come to appreciate over my three decades…

-

Lionhead Goldfish

The Lionhead Goldfish represents one of the most distinctive and cherished ornamental varieties within the goldfish family, captivating aquarists…

-

Texas Cichlid

The Texas Cichlid (Herichthys cyanoguttatus) stands as one of North America’s most distinctive freshwater fish species, representing the sole…

-

Killifish

Killifish represent one of the most diverse and ecologically significant groups of small freshwater and brackish water fish, comprising…