Sandbar Shark

By Ryan Maron | Last Modified: July 7, 2025

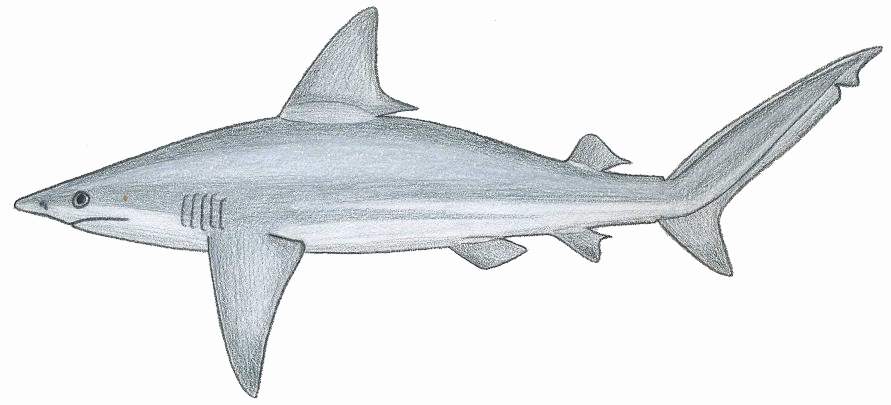

The Sandbar Shark (Carcharhinus plumbeus) stands as one of the most recognizable and ecologically significant members of the requiem shark family along temperate and tropical coastlines worldwide. Distinguished by its prominent triangular dorsal fin and robust build, this species plays a crucial role as a mesopredator in nearshore marine ecosystems. The Sandbar Shark’s position in the food web makes it both predator and prey, helping maintain the delicate balance of coastal fish populations while serving as an indicator species for ecosystem health.

This shark’s importance extends beyond ecological boundaries into commercial and recreational fisheries, where it has historically supported significant economic activity. However, decades of fishing pressure have led to population declines that highlight the vulnerability of slow-growing shark species to overexploitation. Understanding the Sandbar Shark’s biology, behavior, and conservation needs becomes essential for maintaining healthy marine ecosystems and sustainable fisheries management.

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Common Name | Sandbar Shark |

| Scientific Name | Carcharhinus plumbeus |

| Family | Carcharhinidae |

| Typical Size | 150-200 cm, 45-90 kg |

| Habitat | Coastal waters, continental shelves |

| Diet | Fish, crustaceans, mollusks |

| Distribution | Atlantic, Pacific, Indian Oceans |

| Conservation Status | Vulnerable |

Taxonomy & Classification

The Sandbar Shark belongs to the order Carcharhiniformes, which encompasses the ground sharks, the largest and most diverse group of modern sharks. Within this order, Carcharhinus plumbeus represents one of approximately 50 species in the genus Carcharhinus, commonly known as requiem sharks. The species was first scientifically described by Charles Alexandre Lesueur in 1818, with the specific epithet “plumbeus” referring to the shark’s lead-gray coloration.

Taxonomic classification places the Sandbar Shark in the family Carcharhinidae, which includes many of the ocean’s most recognizable shark species. This family is characterized by the presence of nictitating membranes (protective eyelids), two dorsal fins, and five gill slits. The requiem sharks are distinguished from other families by their streamlined bodies, pointed snouts, and blade-like teeth adapted for cutting prey.

Recent molecular studies have confirmed the monophyletic nature of the Carcharhinus genus, supporting traditional morphological classifications. The Sandbar Shark’s closest relatives include other large coastal species such as the Bull Shark and dusky shark, with which it shares similar ecological niches and life history traits. Genetic analysis indicates that the Sandbar Shark lineage diverged from its sister species approximately 10-15 million years ago during the Miocene epoch.

The species exhibits some geographical variation in morphology and genetics, leading to ongoing research into potential subspecies designations. Atlantic and Pacific populations show subtle differences in vertebral counts and fin proportions, though these variations fall within the range of individual variation rather than warranting separate taxonomic recognition.

Physical Description

The Sandbar Shark displays the classic requiem shark body plan with several distinctive characteristics that facilitate identification. Adults typically measure 150-200 centimeters in total length, with females generally growing larger than males. The maximum recorded length exceeds 240 centimeters, though such large individuals are increasingly rare in heavily fished populations. Adult weight ranges from 45-90 kilograms, with exceptional specimens reaching over 100 kilograms.

The most distinctive feature of the Sandbar Shark is its exceptionally tall, triangular first dorsal fin, which is proportionally larger than that of most other requiem sharks. This dorsal fin originates well forward on the body, positioned over or slightly behind the pectoral fins’ rear margins. The second dorsal fin is much smaller and positioned above the anal fin. The pectoral fins are notably long and falcate, contributing to the shark’s efficient swimming capabilities.

Coloration follows a typical shark pattern with a bronze to gray-brown dorsal surface that gradually transitions to white or pale yellow on the ventral side. This countershading provides camouflage when viewed from above or below. Juvenile Sandbar Sharks may exhibit slightly darker coloration with more pronounced contrast between dorsal and ventral surfaces.

The head profile is moderately rounded with a relatively short, broadly rounded snout. The eyes are circular and moderately large, equipped with nictitating membranes for protection during feeding. The mouth is positioned on the underside of the head and contains 13-15 tooth rows on each side of both jaws. The teeth are triangular and serrated, designed for cutting rather than grasping, reflecting the species’ feeding habits.

Body proportions indicate adaptation for sustained swimming and maneuverability in coastal environments. The caudal fin is heterocercal with a well-developed lower lobe, providing thrust and stability during swimming. The interdorsal ridge is prominent, contributing to hydrodynamic efficiency and distinguishing the species from similar sharks that lack this feature.

Habitat & Distribution

The Sandbar Shark inhabits temperate and tropical coastal waters across three major ocean basins, demonstrating remarkable adaptability to diverse marine environments. In the Atlantic Ocean, populations extend from Massachusetts to southern Brazil in the western Atlantic, and from the North Sea to Angola in the eastern Atlantic. Pacific populations range from southern California to Ecuador in the eastern Pacific, while western Pacific populations occur from Japan to Australia.

Within its range, the Sandbar Shark primarily occupies continental shelf waters from the shoreline to depths of approximately 280 meters. The species shows strong preferences for sandy and muddy bottoms, which provide optimal foraging conditions for benthic prey species. Juveniles and adults utilize different habitat zones, with juveniles concentrating in shallow estuarine and nearshore areas that offer protection from larger predators.

Nursery areas represent critical habitat components for Sandbar Shark populations. These areas typically occur in shallow bays, estuaries, and coastal lagoons where water temperatures remain relatively stable and prey abundance is high. Major nursery areas along the U.S. Atlantic coast include the Chesapeake Bay, Delaware Bay, and various North Carolina sounds. These protected environments provide essential habitat for young sharks during their most vulnerable life stages.

Temperature preferences influence the species’ distribution patterns, with optimal ranges between 16-32°C. Seasonal migrations occur in response to temperature changes, with sharks moving to deeper waters during winter months and returning to shallow areas during spring and summer. These movements can span hundreds of kilometers and are often related to reproductive cycles and prey availability.

The species demonstrates site fidelity to specific areas, particularly nursery grounds and mating areas. Tagging studies have revealed that individual sharks may return to the same general areas across multiple years, suggesting strong natal site fidelity. This behavior has important implications for population structure and management, as localized fishing pressure can significantly impact specific population segments.

Salinity tolerance allows Sandbar Sharks to venture into brackish estuarine waters, though they remain primarily marine. The species rarely enters freshwater systems, distinguishing it from more euryhaline species like the Bull Shark that can tolerate extended periods in freshwater environments.

Diet & Feeding Behavior

The Sandbar Shark exhibits opportunistic feeding behavior with a diet that shifts considerably throughout its life cycle. Juveniles primarily consume small benthic invertebrates, including crabs, shrimp, and other crustaceans, along with small bony fish species. As sharks mature, their diet expands to include larger prey items, with adult Sandbar Sharks targeting medium-sized fish, rays, and occasionally other sharks.

Feeding patterns demonstrate both benthic and pelagic foraging strategies. The species’ flattened head and inferior mouth position facilitate bottom feeding, allowing sharks to capture prey buried in sediment or residing on the seafloor. Crustaceans constitute a significant portion of the diet, particularly blue crabs, hermit crabs, and various shrimp species. The sharks’ crushing posterior teeth are well-adapted for processing hard-shelled prey.

Fish prey includes a diverse array of species depending on local availability and seasonal abundance. Common prey fish include croakers, spot, Atlantic menhaden, and various flatfish species. Sandbar Sharks also consume cephalopods, including squid and octopus, though these represent a smaller component of the overall diet. The species’ ability to exploit multiple prey types provides resilience against fluctuations in individual prey populations.

Feeding behavior varies with tidal cycles and diel patterns. Many Sandbar Sharks exhibit increased activity during dawn and dusk periods, coinciding with prey movement patterns. Tidal influences affect prey availability, with sharks often feeding more actively during incoming tides that bring prey into shallow foraging areas.

Cooperative feeding behaviors have been observed in some situations, particularly when large concentrations of prey are available. However, Sandbar Sharks are generally solitary feeders that rely on individual hunting strategies rather than coordinated group efforts. The species’ feeding ecology plays an important role in nutrient cycling within coastal ecosystems, transferring energy from benthic communities to higher trophic levels.

Seasonal variations in diet reflect prey availability and the sharks’ migratory patterns. During summer months in nursery areas, juvenile sharks may specialize on abundant crab species, while winter feeding in deeper waters may emphasize fish prey. These adaptive feeding strategies allow Sandbar Sharks to maintain energy reserves necessary for growth and reproduction despite seasonal changes in prey communities.

Behavior & Adaptations

Sandbar Sharks display complex behavioral patterns that reflect their position as mesopredators in marine ecosystems. The species exhibits strong site fidelity, with individuals returning to specific areas for feeding, mating, and nursery purposes. This homing behavior is facilitated by sophisticated navigation abilities that likely involve magnetic field detection, chemical cues, and possibly celestial navigation.

Swimming behavior demonstrates remarkable efficiency, with Sandbar Sharks capable of sustained cruising speeds of 3-5 kilometers per hour and burst speeds exceeding 25 kilometers per hour when pursuing prey or avoiding threats. Their swimming pattern typically involves steady, rhythmic movements that minimize energy expenditure while maintaining forward momentum. The species’ hydrodynamic body shape and powerful caudal fin enable efficient locomotion across various marine environments.

Social behaviors vary by life stage and environmental conditions. Juveniles often form loose aggregations in nursery areas, which may provide protection from predators through the dilution effect. Adult sharks are generally more solitary, though temporary aggregations may occur during feeding opportunities or reproductive periods. These aggregations rarely involve complex social interactions but rather represent responses to environmental conditions or resource availability.

Thermoregulatory adaptations allow Sandbar Sharks to maintain activity across a range of temperatures. Unlike some shark species that possess specialized heat-exchanging blood vessels, Sandbar Sharks rely on behavioral thermoregulation, seeking optimal temperature zones through vertical and horizontal movements. This behavior is particularly important during seasonal migrations when sharks encounter varying thermal conditions.

Sensory adaptations include highly developed electroreception capabilities through the ampullae of Lorenzini, which detect electrical fields generated by prey organisms. This system is particularly effective for locating buried prey in sediment, complementing the sharks’ benthic feeding strategies. The lateral line system provides additional sensory input for detecting water movements and pressure changes associated with prey or predator activity.

Predator avoidance behaviors become particularly important for juvenile sharks, which face predation pressure from larger sharks, rays, and bony fish. Behavioral responses include seeking shelter in structured habitats, utilizing shallow water refugia, and exhibiting increased vigilance in areas with high predator densities. These behaviors contribute to size-structured habitat use patterns observed in many shark populations.

Resting behavior in Sandbar Sharks involves periods of reduced activity, often associated with specific bottom types or structural features. Unlike some shark species that require constant motion for respiration, Sandbar Sharks can pump water over their gills while stationary, allowing for energy conservation during inactive periods.

Reproduction & Life Cycle

The Sandbar Shark exhibits a classic K-selected life history strategy characterized by slow growth, late maturity, and low reproductive output. This reproductive strategy makes the species particularly vulnerable to overexploitation and complicates population recovery efforts. Understanding these reproductive parameters is crucial for effective fisheries management and conservation planning.

Sexual maturity is reached at approximately 12-15 years of age, with males typically maturing slightly earlier than females. Size at maturity varies geographically, with males generally reaching maturity at 130-140 centimeters total length and females at 140-150 centimeters. The extended juvenile period reflects the species’ investment in growth and survival before committing energy to reproduction.

Mating occurs during specific seasonal periods, typically in late spring or early summer in temperate regions. Courtship behaviors include following, parallel swimming, and physical contact between males and females. Males possess claspers, modified pelvic fins used for sperm transfer during copulation. Mating may occur in specific areas that serve as seasonal aggregation sites for reproductive adults.

The Sandbar Shark is viviparous, meaning females give birth to live young after an extended gestation period. Embryonic development occurs within the mother’s uterus, with developing sharks initially sustained by yolk reserves and later receiving additional nutrition through a placental connection. This reproductive mode provides developing young with optimal conditions for growth and development.

Gestation periods extend 9-12 months, representing a significant energetic investment for females. Litter sizes range from 1-14 pups, with an average of 6-8 young per litter. Larger females typically produce more offspring, though reproductive success can be influenced by environmental conditions and the female’s nutritional status. The extended gestation period and relatively small litter sizes contribute to the species’ low reproductive potential.

Parturition occurs in shallow nursery areas that provide optimal conditions for newborn survival. Females exhibit strong site fidelity to specific nursery grounds, often returning to the same areas where they were born. This natal philopatry creates population structure and has important implications for fisheries management, as localized fishing pressure can disproportionately impact specific population segments.

Newborn Sandbar Sharks measure approximately 55-65 centimeters at birth and are immediately independent, receiving no parental care after birth. The relatively large birth size provides advantages in predator avoidance and foraging capability compared to smaller newborns. Juvenile sharks remain in nursery areas for several years, gradually expanding their habitat range as they grow.

Reproductive cycles are not annual, with females requiring 2-3 years between reproductive events to recover from the energetic costs of gestation and parturition. This extended reproductive cycle further reduces the species’ population growth potential and recovery ability following population declines.

Predators & Threats

The Sandbar Shark faces different predation pressures throughout its life cycle, with vulnerability generally decreasing as individuals grow larger. Juvenile sharks are subject to predation by a variety of marine predators, including larger sharks, rays, and bony fish species. Common predators of young Sandbar Sharks include Bull Sharks, Tiger Sharks, and various ray species that forage in nursery areas.

Adult Sandbar Sharks have few natural predators due to their size and defensive capabilities. However, they may occasionally fall prey to larger shark species, particularly in areas where multiple large predators overlap. The species’ robust build and swimming capabilities provide effective defense mechanisms against most potential predators.

Anthropogenic threats represent the most significant challenge to Sandbar Shark populations worldwide. Commercial fishing operations have historically targeted the species for its valuable fins, meat, and liver oil. The sharks’ predictable aggregation patterns and coastal habitat preferences make them particularly vulnerable to fishing pressure. Directed fisheries and incidental capture in other fishing operations have contributed to population declines across much of the species’ range.

Habitat degradation poses an increasingly serious threat to Sandbar Shark populations. Coastal development, pollution, and climate change impacts affect critical nursery areas and feeding grounds. Water quality degradation from agricultural runoff, industrial discharge, and urban development can reduce prey availability and create unsuitable conditions for reproduction and juvenile survival.

Bycatch in commercial fishing operations represents a significant source of mortality for Sandbar Sharks. The species is frequently caught incidentally in bottom trawls, gill nets, and longline fisheries targeting other species. While some bycatch regulations exist, enforcement challenges and the widespread nature of fishing operations make this a persistent threat.

Climate change effects include rising sea temperatures, ocean acidification, and changing precipitation patterns that affect estuarine nursery areas. These changes may alter prey distributions, affect reproductive success, and require shifts in the species’ distribution patterns. The sharks’ limited dispersal capabilities and strong site fidelity may constrain their ability to adapt to rapid environmental changes.

Pollution from various sources affects Sandbar Shark populations through bioaccumulation of toxins and habitat degradation. Heavy metals, pesticides, and other contaminants can accumulate in shark tissues, potentially affecting reproduction, growth, and survival. Plastic pollution represents an emerging threat through both ingestion and entanglement.

The cumulative impact of multiple threats creates particular challenges for Sandbar Shark conservation. The species’ life history characteristics make recovery from population declines a slow process, requiring comprehensive management approaches that address multiple threat sources simultaneously.

Conservation Status

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classifies the Sandbar Shark as Vulnerable on the Red List of Threatened Species, reflecting significant population declines documented across much of its range. This designation indicates that the species faces a high risk of extinction in the wild without effective conservation measures. Population assessments have revealed declines exceeding 50% in many regions over the past three generations.

In the United States, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) has implemented comprehensive management measures for Sandbar Shark populations under the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act. These measures include commercial quotas, recreational bag limits, and seasonal closures designed to reduce fishing mortality and protect critical life stages. The species is also protected under various state regulations that provide additional conservation measures in state waters.

Stock assessments conducted by NOAA Fisheries indicate that Atlantic Sandbar Shark populations are rebuilding following implementation of strict management measures in the 1990s. However, recovery remains slow due to the species’ life history characteristics, and populations have not yet returned to historical levels. The rebuilding timeline extends several decades, reflecting the challenges of recovering long-lived, slow-growing species.

International conservation efforts include the species’ listing under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) Appendix II, which regulates international trade in Sandbar Shark products. This designation requires exporting countries to demonstrate that trade is not detrimental to the survival of the species and comes from sustainable sources.

Regional fisheries management organizations have implemented various conservation measures for Sandbar Sharks within their jurisdictions. The International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) has established recommendations for shark conservation that include retention prohibitions for certain species and requirements for shark finning regulations.

Research programs continue to monitor Sandbar Shark populations through various methods, including fisheries-independent surveys, tagging studies, and life history research. These programs provide essential data for stock assessments and adaptive management approaches. Collaborative research between government agencies, academic institutions, and fishing industry representatives helps ensure comprehensive data collection and stakeholder involvement in conservation planning.

Conservation challenges include enforcement of existing regulations, addressing bycatch in fisheries targeting other species, and protecting critical habitats from development and degradation. The species’ migratory nature requires coordinated management efforts across jurisdictional boundaries, making international cooperation essential for effective conservation.

Public awareness campaigns and educational programs play important roles in Sandbar Shark conservation by promoting understanding of the species’ ecological importance and conservation needs. These efforts help build support for conservation measures and encourage responsible fishing practices among recreational and commercial fishers.

Human Interaction

Human interactions with Sandbar Sharks span multiple sectors, including commercial fisheries, recreational fishing, and ecotourism. Historically, the species supported significant commercial fisheries that targeted sharks for their fins, meat, and liver oil. The valuable nature of shark fins in international markets created strong economic incentives for fishing operations, leading to intensive exploitation of Sandbar Shark populations.

Commercial fishing operations have employed various gear types to capture Sandbar Sharks, including longlines, gill nets, and bottom trawls. The species’ predictable seasonal movements and aggregation patterns made them particularly vulnerable to targeted fishing efforts. Commercial landings peaked in the 1980s and 1990s before declining due to both population reductions and increased management restrictions.

Recreational fishing for Sandbar Sharks occurs throughout the species’ range, with anglers targeting sharks from shore, piers, and boats. The species’ fighting ability and size make it popular among recreational fishers, though catch-and-release practices have become more common as conservation awareness has increased. Recreational fishing regulations typically include size limits, bag limits, and seasonal restrictions designed to reduce fishing mortality.

The meat of Sandbar Sharks is consumed in various forms, including fresh, frozen, and processed products. However, concerns about mercury contamination and the species’ conservation status have reduced market demand in some regions. Sustainable seafood programs now provide guidance to consumers about the conservation implications of shark consumption.

Shark fin soup and other traditional dishes have driven international trade in Sandbar Shark fins, contributing to fishing pressure on populations worldwide. International regulations and changing consumer preferences have begun to reduce demand for shark fin products, though illegal trade continues in some regions.

Ecotourism operations occasionally feature Sandbar Sharks as attractions, though the species’ coastal habitat preferences make them less commonly encountered than some other shark species. Educational programs and aquarium displays help promote public understanding of shark biology and conservation needs.

Attacks on humans by Sandbar Sharks are extremely rare, with the species generally exhibiting docile behavior around humans. The few documented interactions typically involve cases of mistaken identity or defensive responses to harassment. The species’ reputation as a relatively harmless shark has contributed to its popularity in research and educational settings.

Scientific research on Sandbar Sharks has contributed significantly to understanding of shark biology, ecology, and conservation needs. Long-term tagging studies have provided insights into migration patterns, population structure, and life history characteristics that inform management decisions. Research collaborations between scientists and fishing industry representatives have improved understanding of fishing impacts and bycatch reduction methods.

Beach safety programs and public education efforts help reduce negative interactions between humans and sharks while promoting conservation awareness. These programs emphasize the importance of sharks in marine ecosystems and the need for protection rather than elimination of shark populations.

Interesting Facts

The Sandbar Shark possesses several remarkable characteristics that distinguish it from other shark species and highlight its ecological importance. One of the most striking features is the species’ exceptional site fidelity, with individual sharks returning to the same nursery areas where they were born after reaching reproductive maturity. This natal philopatry creates genetically distinct population segments that have important implications for conservation and management.

Tagging studies have revealed impressive migration capabilities, with some Sandbar Sharks traveling over 3,000 kilometers between feeding and reproductive areas. These migrations demonstrate the species’ remarkable navigation abilities and the importance of protecting habitats across their entire range. The longest recorded migration involved a shark tagged off the coast of Virginia that was recaptured near Venezuela, highlighting the international nature of shark conservation needs.

The species exhibits remarkable longevity, with some individuals living over 30 years in the wild. This extended lifespan, combined with late maturity and low reproductive rates, makes Sandbar Sharks particularly vulnerable to overexploitation. Age determination studies using vertebral growth rings have provided crucial information for stock assessments and management planning.

Sandbar Sharks possess an unusual feeding adaptation that allows them to process hard-shelled prey efficiently. Their posterior teeth are modified for crushing, while anterior teeth are designed for cutting, creating a dual-purpose dental system. This adaptation enables the species to exploit a diverse range of prey types, from soft-bodied fish to hard-shelled crustaceans.

The species demonstrates remarkable depth tolerance, with individuals recorded at depths exceeding 280 meters. This vertical habitat use allows Sandbar Sharks to exploit prey resources across different depth zones and may provide thermal refugia during extreme weather events. Deep-water movements are often associated with winter months when sharks seek more stable temperature conditions.

Sandbar Sharks play a crucial role in marine ecosystems as both predator and prey, transferring energy between different trophic levels. Their feeding activities help control populations of benthic invertebrates and fish, while their presence supports populations of larger predators. This keystone role makes their conservation important for maintaining ecosystem balance.

The species exhibits sexual dimorphism beyond size differences, with males developing longer claspers and more pronounced muscular development around the head region. These differences become more pronounced during reproductive periods and may play roles in mate selection and competitive interactions.

Research has revealed that Sandbar Sharks possess sophisticated sensory capabilities, including the ability to detect electrical fields as weak as 0.01 microvolts per centimeter. This electroreception system is among the most sensitive known in the animal kingdom and allows sharks to locate prey buried in sediment or detect the bioelectric fields of other organisms.

Temperature preferences influence not only distribution patterns but also metabolic rates and feeding behavior. Sandbar Sharks in warmer waters exhibit higher metabolic rates and may require more frequent feeding, while those in cooler waters can survive longer periods between meals. This physiological flexibility contributes to the species’ wide geographic distribution.

The species’ contribution to marine research extends beyond basic biology to include biomechanical studies of swimming efficiency and sensory biology research. Sandbar Sharks have served as model organisms for understanding shark physiology and behavior, contributing to broader scientific knowledge about marine ecosystems.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Sandbar Sharks dangerous to humans?

Sandbar Sharks are generally considered one of the less dangerous shark species to humans. They exhibit docile behavior and rarely interact aggressively with people. The few documented incidents typically involve cases of mistaken identity or defensive responses when sharks are harassed or cornered. Their preference for deeper waters and bottom-dwelling prey means encounters with swimmers and divers are relatively uncommon.

How can you identify a Sandbar Shark?

The most distinctive identifying feature of a Sandbar Shark is its exceptionally tall, triangular first dorsal fin that originates over or slightly behind the pectoral fins. The species also has a relatively short, rounded snout, bronze to gray-brown coloration on the back, and a prominent interdorsal ridge. The combination of these features, along with their robust build and long pectoral fins, makes them relatively easy to distinguish from other requiem sharks.

What is the current population status of Sandbar Sharks?

Sandbar Shark populations have experienced significant declines, leading to their classification as Vulnerable by the IUCN. In the United States, Atlantic populations are showing signs of recovery following implementation of strict management measures in the 1990s, but recovery remains slow due to the species’ life history characteristics. Full population recovery is expected to take several decades even with continued protection.

Where do Sandbar Sharks give birth?

Sandbar Sharks give birth in shallow nursery areas, typically in bays, estuaries, and coastal lagoons. Major nursery areas along the U.S. Atlantic coast include the Chesapeake Bay, Delaware Bay, and various sounds along the North Carolina coast. These areas provide optimal conditions for newborn survival, including warmer water temperatures, abundant prey, and protection from larger predators.

Conclusion

The Sandbar Shark represents a critical component of marine ecosystems whose conservation requires comprehensive, long-term management approaches. As a mesopredator with complex life history requirements, this species serves as an indicator of ecosystem health while facing significant challenges from human activities. The species’ slow recovery following population declines underscores the importance of precautionary management and the need for continued research and monitoring to ensure sustainable populations for future generations.

Share The Article:

More Fish Species:

-

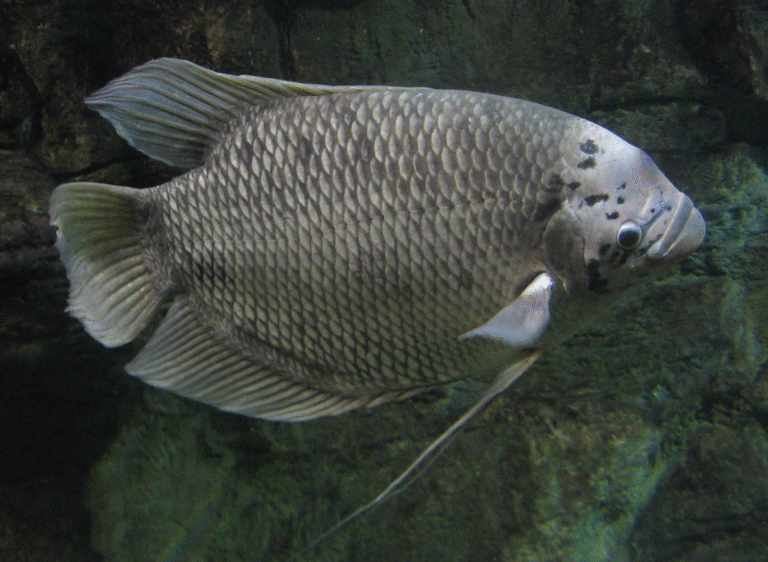

Giant Gourami

The Giant Gourami (Osphronemus goramy) represents one of the most remarkable freshwater fish species in Southeast Asia, distinguished by…

-

Variable Platyfish

The Variable Platyfish (Xiphophorus variatus) stands as one of the most widely recognized and ecologically significant freshwater fish species…

-

Red Devil Cichlid

The Red Devil Cichlid stands as one of Central America’s most formidable and captivating freshwater predators, renowned for its…

-

Black Neon Tetra

The Black Neon Tetra (Hyphessobrycon herbertaxelrodi) stands as one of the most distinctive freshwater fish species in the aquarium…

-

Cichlid

Cichlids represent one of the most diverse and fascinating families of freshwater fish, encompassing over 1,700 species distributed across…

-

Goldfish

The goldfish (Carassius auratus) stands as one of the most culturally significant and scientifically fascinating species in freshwater aquaculture…

Discover

-

Crappie Fishing Guide for Beginners | 2025

Crappie fishing might just be one of the most rewarding experiences for new anglers. These popular panfish are abundant,…

-

Fishing Ethics: Conservation, Catch-and-Release, and Angler Responsibility

I was ten years old when my grandfather caught me throwing rocks at a school of bluegill near our…

-

Texas Saltwater Fishing: Essential Tips From Adam

It was June 2010, and man was I cocky heading into that first Texas saltwater trip. Drove down from…

-

15 Panfish Fishing Secrets: Easy Catches for Beginners & Pros

You know what’s funny about panfish? These little fighters have probably hooked more new anglers than any other species,…

-

How to Fish for Bluegill: 2025 Complete Guide

Bluegill might not be the biggest fish in the pond, but they sure make up for it in fight…

-

History of Fly Fishing: Ancient Origins to Modern Mastery

The gentle art of fly fishing has captivated anglers for centuries, evolving from a practical method of obtaining food…

Discover

-

Beluga Fishing: Techniques That Actually Work (Not Theory)

When it comes to beluga fishing, there’s a world of difference between what you read in theory and what…

-

Best Fishing Spots in California: Lakes, Rivers, and Coastal Hotspots

California fishing has always struck me as a study in beautiful contradictions. From snow-fed alpine lakes to sweltering desert…

-

Smallmouth Black Bass Fishing: Complete Guide for 2025

If you’ve ever felt that sudden, powerful tug on your line followed by an acrobatic jump that leaves your…

-

Bleeding Heart Tetra

The Bleeding Heart Tetra represents one of the most distinctive and peaceful freshwater fish species in the aquarium trade,…

-

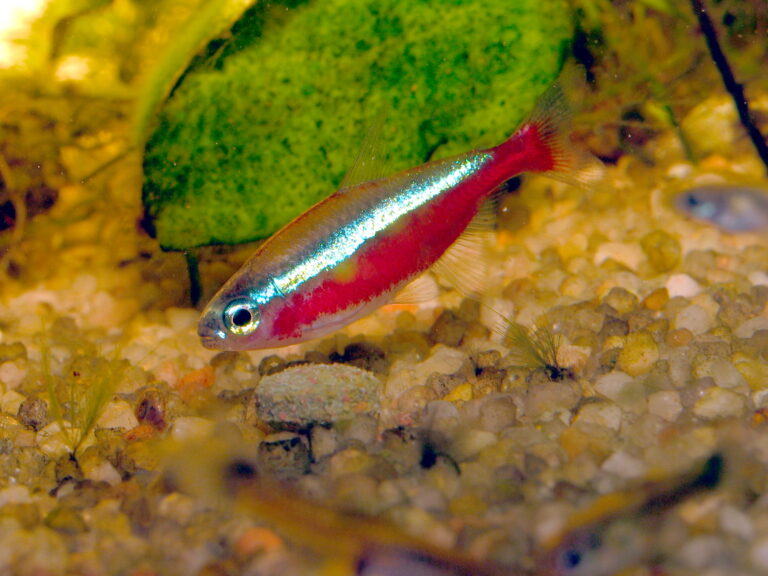

Cardinal Tetra

The Cardinal Tetra (Paracheirodon axelrodi) stands as one of the most vibrant and sought-after freshwater aquarium fish in the…

-

Best Time to Go Fishing: Timing Tips for Bigger Catches

If there’s one question I get asked more than any other, it’s about timing. When should you cast that…