Nurse Shark

By Ryan Maron | Last Modified: July 12, 2025

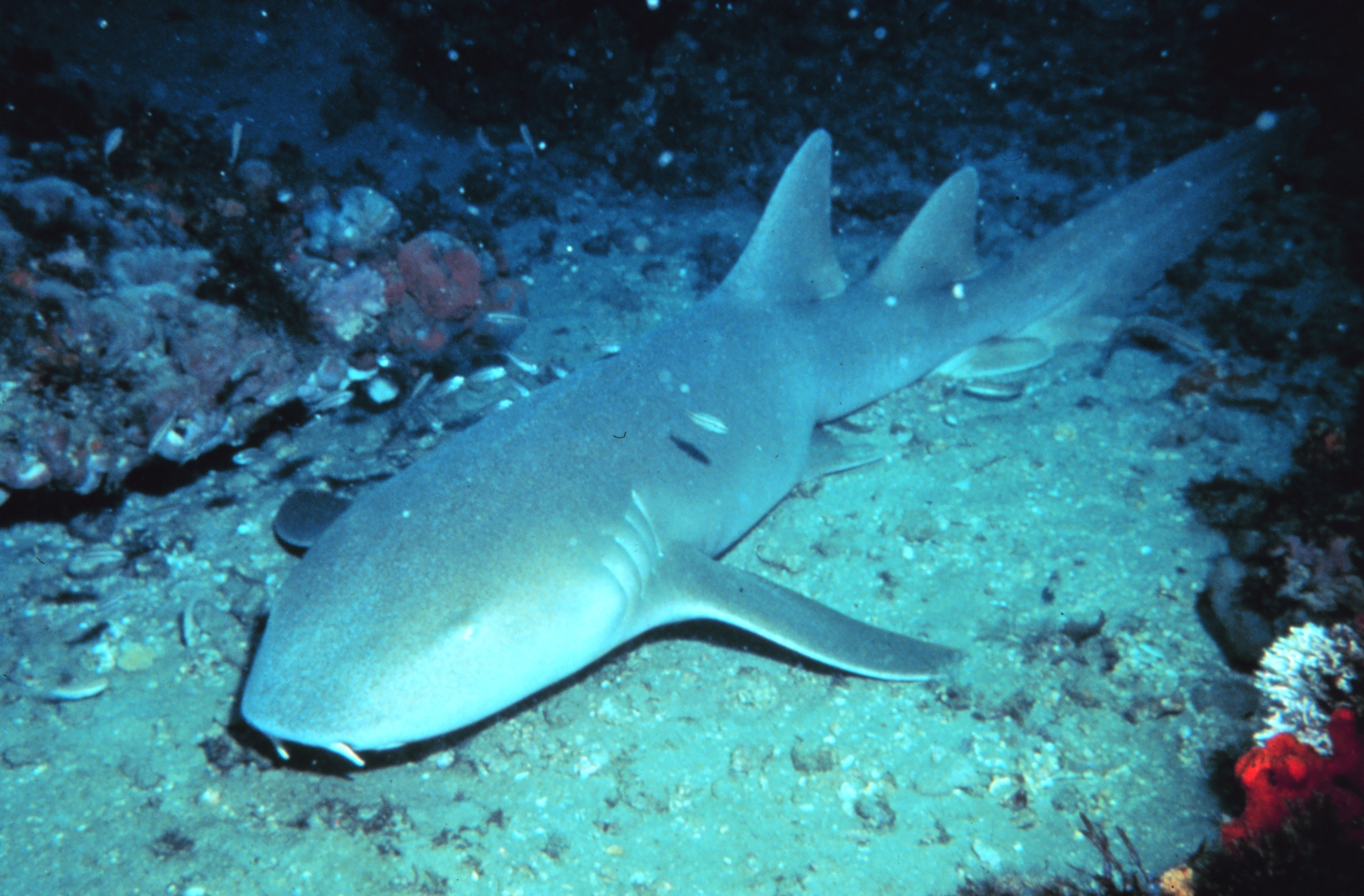

The Nurse Shark (Ginglymostoma cirratum) stands as one of the most recognizable and ecologically significant bottom-dwelling sharks in tropical and subtropical waters. This robust elasmobranch species plays a crucial role as both predator and prey in shallow marine ecosystems, contributing to the delicate balance of reef and coastal environments. Unlike many of their more aggressive relatives, Nurse Sharks exhibit relatively docile behavior, making them important subjects for marine research and ecotourism activities.

As a keystone species in many Caribbean and western Atlantic reef systems, the Nurse Shark influences population dynamics of numerous invertebrate and small fish species through its specialized feeding behavior. These sharks serve as natural biocontrol agents, regulating populations of crustaceans, mollusks, and small fish that inhabit coral reefs and seagrass beds. Their presence indicates healthy ecosystem function, while their absence often signals environmental degradation.

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Common Name | Nurse Shark |

| Scientific Name | Ginglymostoma cirratum |

| Family | Ginglymostomatidae |

| Typical Size | 230-300 cm (7.5-10 ft), 75-120 kg |

| Habitat | Shallow coastal waters, coral reefs |

| Diet | Benthic invertebrates, small fish |

| Distribution | Western Atlantic, Caribbean, Eastern Pacific |

| Conservation Status | Vulnerable (IUCN) |

Taxonomy & Classification

The Nurse Shark belongs to the family Ginglymostomatidae, commonly known as carpet sharks or nurse sharks. This taxonomic classification places Ginglymostoma cirratum within the order Orectolobiformes, which encompasses bottom-dwelling sharks characterized by their flattened bodies and specialized feeding apparatus. The genus Ginglymostoma contains only three recognized species, with G. cirratum being the most widely distributed and well-studied member.

Phylogenetic analysis indicates that nurse sharks diverged from other carpet shark lineages approximately 50 million years ago during the Eocene epoch. Their evolutionary history reflects adaptations to benthic environments, with morphological features optimized for life on sandy bottoms and coral reefs. The species name “cirratum” refers to the distinctive barbels or cirri that extend from the nostrils, serving as chemosensory organs crucial for prey detection.

Recent molecular studies have revealed genetic variations within G. cirratum populations across different geographic regions, suggesting possible subspecies differentiation. Caribbean populations show distinct genetic markers compared to those in the eastern Pacific, indicating limited gene flow between these regions. This genetic diversity underscores the importance of regional conservation efforts to preserve local adaptations.

Physical Description

Nurse Sharks exhibit a robust, cylindrical body shape that distinguishes them from more streamlined pelagic species. Adult specimens typically reach lengths of 230-300 centimeters, with females generally growing larger than males. The maximum recorded length exceeds 430 centimeters, though such giants are increasingly rare due to fishing pressure. Their weight typically ranges from 75-120 kilograms, with exceptional individuals reaching 200 kilograms.

The species displays a distinctive flattened head with a rounded snout and subterminal mouth positioned well below the rostrum. Two prominent barbels extend from the nostrils, measuring 3-4 centimeters in length and serving as highly sensitive chemoreceptors. These barbels constantly probe the substrate, detecting chemical signatures of buried prey items. The mouth contains rows of small, pointed teeth designed for grasping rather than cutting, reflecting their diet of small prey items.

Coloration varies from yellowish-brown to dark brown dorsally, with a lighter ventral surface. Young individuals often display distinct dark spots or bands that fade with age, providing excellent camouflage among coral formations and rocky substrates. The skin texture is notably rough due to placoid scales, which reduce drag during swimming and provide protection against abrasion when navigating tight spaces in reef environments.

The dorsal fins are positioned relatively far back on the body, with the first dorsal fin originating posterior to the pelvic fins. This fin arrangement reflects their bottom-dwelling lifestyle, providing stability during benthic foraging rather than high-speed swimming capability. The caudal fin lacks the pronounced heterocercal structure seen in many shark species, instead displaying a more symmetrical design suited for maneuvering in confined spaces.

Habitat & Distribution

Nurse Sharks inhabit shallow coastal waters throughout the tropical and subtropical western Atlantic, ranging from Rhode Island to southern Brazil, including the entire Caribbean basin. A separate population exists in the eastern Pacific, from Baja California to Ecuador, though genetic evidence suggests these populations represent distinct lineages. The species shows strong site fidelity, with individuals often returning to the same resting sites and foraging areas repeatedly.

Their preferred habitats include coral reefs, seagrass beds, mangrove channels, and sandy flats in depths ranging from intertidal zones to approximately 130 meters. Water temperature preferences range from 22-28°C, with individuals showing seasonal movements in response to thermal gradients. During cooler months, populations in subtropical regions may migrate to deeper waters or seek thermally stable environments near springs or thermal vents.

The species demonstrates remarkable habitat plasticity, successfully occupying diverse marine environments from pristine coral reefs to degraded coastal areas. This adaptability has contributed to their relatively stable population status compared to more specialized shark species. However, their preference for shallow coastal waters places them in direct contact with human activities, creating both opportunities for ecotourism and risks from development pressure.

Nurse Sharks exhibit strong preferences for complex bottom topography, utilizing caves, overhangs, and coral formations for daytime resting sites. These shelters provide protection from predators and reduce energy expenditure during inactive periods. Group resting behavior is common, with multiple individuals often sharing the same shelter, particularly during cooler months when metabolic rates decrease.

Diet & Feeding Behavior

As opportunistic bottom feeders, Nurse Sharks consume a diverse array of benthic invertebrates and small fish species. Their diet consists primarily of crustaceans (40-60%), mollusks (15-25%), small fish (10-20%), and various other invertebrates including sea urchins, polychaete worms, and occasionally small stingrays. This dietary flexibility allows them to exploit different prey resources based on seasonal availability and habitat characteristics.

The feeding mechanism involves powerful suction created by rapid expansion of the buccal cavity, enabling the shark to extract prey from crevices and sandy substrates. This suction feeding capability, combined with their sensitive barbels, makes them highly effective at locating and capturing cryptic prey items. The pharyngeal teeth crush hard-shelled prey, while the gastric acid dissolves shell fragments and exoskeletons.

Foraging behavior typically occurs during twilight hours and throughout the night, when many prey species emerge from daytime shelters. Nurse Sharks employ a systematic searching pattern, methodically investigating potential prey habitats using their barbels to probe sand, rubble, and coral crevices. Their slow, deliberate movements conserve energy while maximizing prey encounter rates.

Seasonal variations in diet composition reflect changes in prey availability and reproductive cycles of invertebrate species. During summer months, when crustacean populations peak, these prey items may comprise up to 70% of the diet. Winter feeding often shifts toward mollusks and fish, as many crustaceans seek deeper waters or reduce activity levels. This dietary plasticity contributes to the species’ ecological success across diverse marine environments.

Behavior & Adaptations

Nurse Sharks exhibit predominantly nocturnal behavior patterns, spending daylight hours resting in sheltered locations and becoming active during twilight and nighttime hours. This behavioral rhythm minimizes energy expenditure while optimizing foraging success, as many prey species are more active during dark periods. Their metabolic rate is approximately 20-30% lower than similarly sized active swimming sharks, reflecting their energy-efficient lifestyle.

Social behavior includes aggregation during resting periods, with groups of 5-40 individuals commonly observed sharing cave systems and overhangs. These aggregations may serve thermoregulatory functions, as clustered individuals maintain more stable body temperatures. Social hierarchies within groups appear minimal, with size-based dominance occasionally observed during feeding situations.

The species demonstrates remarkable site fidelity, with tagging studies revealing that individuals often return to the same resting sites repeatedly over periods of several years. Home range sizes vary from 0.5-15 square kilometers, depending on habitat complexity and prey distribution. This strong site attachment makes populations particularly vulnerable to localized habitat degradation or fishing pressure.

Nurse Sharks possess several physiological adaptations that enhance their bottom-dwelling lifestyle. Their gill slits are positioned laterally rather than ventrally, preventing sediment intrusion during benthic foraging. Specialized spiracles behind the eyes facilitate water flow over the gills when the mouth is buried in substrate. Additionally, their swim bladder is reduced compared to pelagic species, providing neutral buoyancy while allowing precise depth control during foraging activities.

Stress response mechanisms include the ability to remain motionless for extended periods, effectively reducing metabolic demands during adverse conditions. This behavioral flexibility allows them to survive in areas with seasonal food scarcity or environmental disturbances. When threatened, they typically seek shelter rather than fleeing, relying on their camouflage and protective coloration for defense.

Reproduction & Life Cycle

Nurse Sharks reach sexual maturity relatively late compared to many fish species, with females maturing at 15-20 years of age and males at 10-15 years. This delayed maturation, combined with their long lifespan of 25-35 years, results in slow population growth rates that make them vulnerable to overexploitation. Sexual dimorphism becomes apparent at maturity, with males developing prominent claspers and females growing larger overall body sizes.

The reproductive cycle follows a biennial pattern, with females producing offspring every other year. Mating occurs during late spring and early summer, involving complex courtship behaviors where males grasp females using their teeth and position themselves for copulation. The mating process can last several hours, with multiple males sometimes competing for access to receptive females.

Nurse Sharks are ovoviviparous, meaning embryos develop within egg cases inside the mother’s body until ready for birth. The gestation period extends 5-6 months, during which females carry 20-50 developing embryos. Intrauterine cannibalism occurs, with larger embryos consuming smaller ones and unfertilized eggs, resulting in 15-25 live births per litter. This reproductive strategy, while reducing total offspring numbers, produces larger, more developed young with higher survival rates.

Newborn Nurse Sharks measure 27-35 centimeters at birth and possess adult-like proportions and coloration patterns. They exhibit immediate independence, dispersing from birth sites to shallow nursery areas characterized by seagrass beds and mangrove channels. These nursery habitats provide abundant prey resources and protection from larger predators, including adult Nurse Sharks and other shark species.

Juvenile growth rates average 10-15 centimeters per year during the first five years, gradually slowing as individuals approach maturity. Environmental factors such as water temperature, prey availability, and habitat quality significantly influence growth rates. Juveniles in optimal habitats may achieve faster growth compared to those in marginal environments, affecting their ultimate size and reproductive success.

Predators & Threats

Adult Nurse Sharks face few natural predators due to their size and defensive capabilities, though larger sharks including Bull Sharks and Tiger Sharks occasionally prey upon juveniles and smaller adults. Great Barracuda and large grouper species may also consume juvenile Nurse Sharks in areas where their ranges overlap. The primary predation pressure occurs during the first year of life, when young sharks are most vulnerable to a variety of predators.

Human activities represent the most significant threat to Nurse Shark populations throughout their range. Commercial and recreational fishing operations target these sharks for their meat, fins, and liver oil, with demand particularly high in Caribbean and Central American markets. Their docile nature and predictable behavior make them easy targets for spear fishing and hook-and-line capture, contributing to localized population declines.

Habitat degradation poses an increasingly serious threat, particularly in shallow coastal areas where development pressure is intense. Coral reef destruction, seagrass bed loss, and mangrove clearing directly impact critical nursery and foraging habitats. Water quality deterioration from agricultural runoff, sewage discharge, and coastal development further degrades the marine environments upon which these sharks depend.

Climate change effects include rising water temperatures, ocean acidification, and altered precipitation patterns that affect coastal habitats. Temperature increases may force populations to seek cooler waters, potentially disrupting established migration patterns and breeding cycles. Ocean acidification threatens the calcifying organisms that form the base of many food webs supporting Nurse Shark populations.

The species’ life history characteristics, including slow growth, late maturation, and low reproductive rates, make populations particularly vulnerable to overexploitation. Recovery from population declines requires decades rather than years, emphasizing the importance of proactive conservation measures. Bycatch mortality in commercial fishing operations targeting other species also contributes to population pressures, particularly in areas with intensive fishing activity.

Conservation Status

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) currently classifies the Nurse Shark as Vulnerable, reflecting declining population trends across much of its range. This designation recognizes the species’ susceptibility to fishing pressure and habitat degradation, while acknowledging that immediate extinction risk remains relatively low compared to more critically endangered shark species. Regional assessments indicate more severe population declines in heavily exploited areas, particularly around densely populated Caribbean islands.

Population monitoring efforts have documented significant declines in several key regions over the past three decades. In the Bahamas, traditionally considered a Nurse Shark stronghold, populations have decreased by an estimated 30-40% since the 1980s. Similar trends have been observed in Florida Keys waters, where development pressure and fishing mortality have contributed to local population reductions. However, some protected areas maintain relatively stable populations, demonstrating the effectiveness of conservation measures.

Current conservation efforts include establishment of marine protected areas, fishing regulations, and international trade monitoring through the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). The species is listed on CITES Appendix II, requiring permits for international trade and enabling monitoring of harvest levels. Several Caribbean nations have implemented complete protection for Nurse Sharks, prohibiting all commercial and recreational harvest.

The comprehensive species assessment by FishBase provides detailed information on global distribution patterns and population trends. Research initiatives focus on understanding population connectivity, identifying critical habitats, and developing sustainable management strategies. Genetic studies are revealing population structure information essential for designing effective conservation programs.

Ecotourism has emerged as an important conservation tool, providing economic incentives for local communities to protect Nurse Shark populations. Diving and snorkeling operations generate significant revenue in areas where these sharks are abundant, creating stakeholder support for conservation measures. Educational programs targeting local communities and tourists help raise awareness about the species’ ecological importance and conservation needs.

Human Interaction

Nurse Sharks have developed a complex relationship with human activities throughout their range, serving as both targets for exploitation and subjects of conservation interest. Their docile temperament and predictable behavior make them popular attractions for marine ecotourism, generating substantial economic benefits for coastal communities. Diving operations frequently feature Nurse Shark encounters, with some locations reporting individual sharks that have become accustomed to human presence over many years.

The species plays an important role in traditional fishing practices throughout the Caribbean, where they are valued for their meat and liver oil. Local fishing communities have developed specialized techniques for capturing Nurse Sharks, including the use of fish traps and bottom-set lines. However, modern fishing pressures have intensified harvest levels beyond sustainable limits in many areas, contributing to population declines.

Aquarium displays featuring Nurse Sharks have become increasingly common in public aquariums worldwide, serving important educational functions while raising questions about the ethics of maintaining large marine predators in captivity. These displays provide opportunities for public education about shark biology and conservation, though they require significant resources and expertise to maintain properly. Breeding programs in captivity have achieved limited success, with few facilities successfully maintaining multi-generational populations.

Scientific research on Nurse Sharks has contributed significantly to our understanding of elasmobranch biology, behavior, and ecology. Their tolerance for handling and relatively calm disposition make them ideal subjects for physiological studies, tracking research, and behavioral observations. Long-term tagging studies have provided valuable insights into movement patterns, habitat use, and population dynamics that inform conservation strategies.

Beach encounters between humans and Nurse Sharks are generally benign, as the species rarely exhibits aggressive behavior toward swimmers or divers. However, their powerful jaws and tenacious grip can cause significant injuries if they are harassed or accidentally stepped upon. Education programs emphasizing proper behavior around marine wildlife help minimize negative interactions while promoting appreciation for these remarkable predators.

Interesting Facts

Nurse Sharks possess several fascinating adaptations that distinguish them from their more well-known relatives. Their ability to pump water over their gills while stationary allows them to rest on the bottom for extended periods, unlike many shark species that must swim continuously to maintain adequate oxygen flow. This buccal pumping mechanism enables them to remain motionless in caves and under ledges for hours at a time.

The species demonstrates remarkable longevity, with some individuals estimated to live over 25 years in the wild. Age determination studies using vertebral analysis have revealed that growth rates slow dramatically after sexual maturity, with some large individuals showing minimal growth for several years. This longevity, combined with their site fidelity, means that individual sharks may inhabit the same reef system for decades.

Nurse Sharks exhibit unique feeding behaviors that set them apart from other bottom-dwelling species. They can create powerful suction forces equivalent to lifting a 15-kilogram weight, enabling them to extract prey from tight crevices and sandy substrates. This suction feeding capability is among the most powerful recorded for any shark species, reflecting their specialization for benthic foraging.

The species’ relationship with other marine life includes several interesting symbiotic associations. Remora fish frequently attach to Nurse Sharks, gaining transportation and feeding opportunities while providing cleaning services. Small cleaner fish also establish cleaning stations where Nurse Sharks regularly visit to have parasites removed, demonstrating complex interspecies relationships within reef ecosystems.

Nurse Sharks possess an unusual ability to survive in very shallow water, sometimes entering areas barely deep enough to cover their bodies. This adaptation allows them to exploit tidal pools and shallow mangrove channels that other large predators cannot access. Their flattened body shape and flexible swimming style enable them to navigate through remarkably tight spaces while foraging.

Behavioral studies have revealed that Nurse Sharks can recognize individual humans and may develop preferences for certain diving guides or researchers. Some individuals have been observed approaching the same diver repeatedly while ignoring others, suggesting sophisticated recognition abilities. This behavioral flexibility contributes to their success in areas with regular human activity.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Nurse Sharks dangerous to humans?

Nurse Sharks are generally not dangerous to humans and are considered one of the most docile shark species. They rarely exhibit aggressive behavior toward swimmers or divers and typically flee when approached. However, they can inflict serious injuries if provoked, harassed, or accidentally stepped upon, as their powerful jaws and tenacious grip can cause significant wounds. The vast majority of Nurse Shark incidents involve divers who attempt to touch or ride the sharks, emphasizing the importance of maintaining respectful distances from all marine wildlife.

What do Nurse Sharks eat in the wild?

Nurse Sharks are opportunistic bottom feeders that consume a diverse diet consisting primarily of benthic invertebrates and small fish. Their diet includes crustaceans like crabs and lobsters (40-60% of their diet), mollusks such as conch and clams (15-25%), small fish including grunts and snappers (10-20%), and various other invertebrates like sea urchins, polychaete worms, and small stingrays. They use their sensitive barbels to locate prey hidden in sand or coral crevices, then employ powerful suction to extract their targets.

How big do Nurse Sharks get?

Nurse Sharks typically reach lengths of 230-300 centimeters (7.5-10 feet) and weigh between 75-120 kilograms (165-265 pounds). Females generally grow larger than males, with the maximum recorded length exceeding 430 centimeters (14 feet) and weights reaching up to 200 kilograms (440 pounds). However, such large individuals are increasingly rare due to fishing pressure. Most Nurse Sharks encountered by divers measure between 180-250 centimeters in length.

Where can I see Nurse Sharks while diving?

Nurse Sharks can be observed throughout the tropical and subtropical western Atlantic, including the Caribbean, Bahamas, Florida Keys, and along the coast from North Carolina to Brazil. Popular diving destinations known for reliable Nurse Shark encounters include the Bahamas, Belize, Honduras, Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, and the Florida Keys. They are typically found resting under ledges, in caves, or on sandy bottoms during daylight hours, becoming more active during twilight and nighttime dives.

Conclusion

The Nurse Shark represents a remarkable example of evolutionary adaptation to benthic marine environments, serving as a crucial component of coral reef and coastal ecosystems throughout the tropical Atlantic. Their role as both predator and prey contributes to the complex food web dynamics that maintain healthy marine communities. While currently classified as Vulnerable, effective conservation measures combined with sustainable ecotourism practices offer hope for maintaining stable populations of these fascinating elasmobranchs for future generations to study and appreciate.

Share The Article:

More Fish Species:

-

Celestial Eye Goldfish

The Celestial Eye Goldfish represents one of the most distinctive varieties within ornamental aquaculture, known scientifically as Carassius auratus….

-

Brown Bullhead

The Brown Bullhead (Ameiurus nebulosus) represents one of North America’s most widespread and ecologically significant freshwater catfish species. This…

-

Dwarf Gourami

The Dwarf Gourami (Trichogaster lalius) stands as one of the most popular freshwater aquarium fish species, renowned for its…

-

White Catfish

The White Catfish represents one of North America’s most adaptable freshwater species, serving as both an important commercial fish…

-

Spotted Bass

The Spotted Bass (Micropterus punctulatus) stands as one of North America’s most distinctive freshwater game fish, renowned for its…

-

Pristella Tetra

The Pristella Tetra (Pristella maxillaris) stands as one of South America’s most distinctive freshwater aquarium species, renowned for its…

Discover

-

Dusky Shark

The Dusky Shark represents one of the most ecologically significant yet vulnerable large predators inhabiting coastal and pelagic waters…

-

Utah Fishing License Guide: Costs, Requirements & Hidden Tips for 2025

When I first planned a fishing trip to Utah’s beautiful waters about a decade ago, figuring out the licensing…

-

Florida Keys Tarpon Fishing: Seasonal Guide and Rigging Tips

I still remember my first tarpon hookup in the Florida Keys like it happened yesterday, not 17 years ago….

-

Kayak Fishing vs Boat Fishing: Which Truly Offers the Best Experience?

There’s nothing quite like the debate that erupts when you ask a group of anglers whether kayak fishing or…

-

Fishing with Kids: How to Make It Fun and Educational

I’ll never forget the look on my son Tommy’s face when he caught his first bluegill. He was six,…

-

Offshore Swordfish fishing: Night Techniques and Premier Gear

The first time I ventured into the darkness 30 miles offshore of Key West for swordfish, I was woefully…

Discover

-

Why Stoner Fish Catch is Different: Unusual Angling Tactics

Let’s face it – some fish just act plain weird. Whether you’re an experienced angler or just starting out,…

-

Zebra Danio

The Zebra Danio (Danio rerio) stands as one of freshwater aquarium keeping’s most recognizable and scientifically significant species. This…

-

Black Molly

The Black Molly represents one of the most recognizable and enduring species in the freshwater aquarium trade, captivating both…

-

Convict Cichlid

The Convict Cichlid (Amatitlania nigrofasciata) stands as one of the most recognizable and widely distributed freshwater fish species in…

-

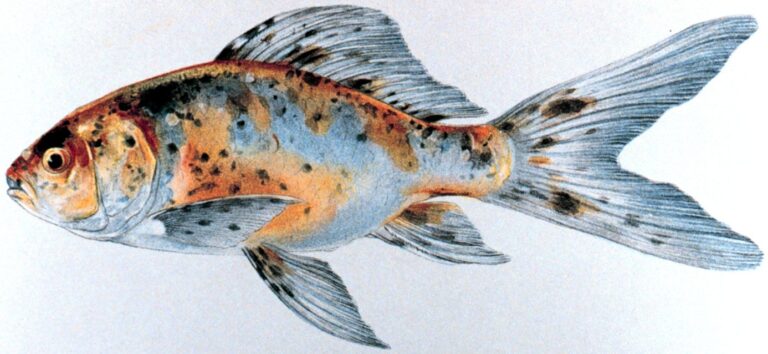

Shubunkin Goldfish

The Shubunkin Goldfish (Carassius auratus) represents one of the most popular and visually striking varieties of goldfish kept in…

-

Longfin Mako Shark

The Longfin Mako Shark represents one of nature’s most enigmatic and misunderstood predators, embodying both the raw power and…