Caribbean Reef Shark

By Ryan Maron | Last Modified: July 13, 2025

The Caribbean Reef Shark (*Carcharhinus perezi*) stands as one of the most recognizable and ecologically significant predators patrolling the warm waters of the western Atlantic Ocean. This robust requiem shark serves as a keystone species within Caribbean coral reef ecosystems, maintaining critical balance through its role as an apex predator while supporting both marine biodiversity and local economies through ecotourism. Distinguished by its stocky build, broad rounded snout, and distinctive gray-brown coloration, the Caribbean Reef Shark has adapted perfectly to life among coral formations, seagrass beds, and sandy bottoms where it hunts a diverse array of prey species.

As a top-level predator, this species plays an essential role in regulating fish populations and maintaining the health of coral reef communities throughout its range. The Caribbean Reef Shark’s presence indicates a healthy marine ecosystem, while its decline often signals broader environmental concerns affecting entire reef systems. Understanding this species becomes increasingly important as climate change and human activities continue to impact Caribbean marine environments, making comprehensive knowledge of its biology, behavior, and conservation needs vital for marine scientists, fisheries managers, and conservation professionals.

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Common Name | Caribbean Reef Shark |

| Scientific Name | Carcharhinus perezi |

| Family | Carcharhinidae |

| Typical Size | 200-250 cm (6.5-8.2 ft), 30-70 kg |

| Habitat | Coral reefs, shallow coastal waters |

| Diet | Carnivorous – reef fish, rays, crustaceans |

| Distribution | Western Atlantic, Caribbean Sea |

| Conservation Status | Near Threatened |

Taxonomy & Classification

The Caribbean Reef Shark belongs to the family Carcharhinidae, commonly known as requiem sharks, which represents the largest family of sharks with over 60 species worldwide. First scientifically described by Poey in 1876, *Carcharhinus perezi* derives its species name from the Cuban naturalist Felipe Poey y Aloy, who contributed significantly to Caribbean marine biology research. The genus *Carcharhinus* encompasses approximately 30 species of medium to large sharks characterized by their streamlined bodies, prominent dorsal fins, and adaptability to various marine environments.

Within the broader taxonomic hierarchy, Caribbean Reef Sharks are classified under the order Carcharhiniformes, which includes the majority of modern shark species. This order evolved during the Jurassic period and represents the most successful group of sharks in terms of species diversity and global distribution. The family Carcharhinidae shares common characteristics including nictitating membranes (protective eyelids), well-developed sensory systems, and live-bearing reproductive strategies.

Recent molecular studies have confirmed the distinct genetic identity of *C. perezi* within the Caribbean basin, distinguishing it from closely related species such as the Dusky Shark (*Carcharhinus obscurus*) and Sandbar Shark (*Carcharhinus plumbeus*). These genetic analyses have revealed limited gene flow between Caribbean populations and other Atlantic *Carcharhinus* species, suggesting a relatively isolated evolutionary history within the Caribbean Sea region.

The species exhibits typical carcharhinid dental morphology, with triangular, serrated teeth in the upper jaw designed for cutting and more narrow, pointed teeth in the lower jaw for grasping prey. This dental arrangement reflects the evolutionary adaptations that have made requiem sharks successful predators across diverse marine ecosystems for millions of years.

Physical Description

Caribbean Reef Sharks exhibit a robust, streamlined body plan perfectly adapted for maneuvering through complex coral reef environments. Adult specimens typically reach lengths of 200-250 centimeters (6.5-8.2 feet), with females generally growing larger than males. The species displays a distinctive gray-brown dorsal coloration that provides excellent camouflage against coral and sandy substrates, while the ventral surface remains pale white, following the classic counter-shading pattern common among pelagic predators.

The head features a broad, rounded snout that distinguishes Caribbean Reef Sharks from other regional *Carcharhinus* species. The eyes are relatively large and equipped with nictitating membranes for protection during feeding activities. The mouth contains 12-15 rows of teeth in each jaw, with the upper teeth being broadly triangular and heavily serrated for efficient cutting of fish and ray tissue. These teeth are continuously replaced throughout the shark’s lifetime, with new teeth moving forward to replace worn or lost ones approximately every two weeks.

Fin morphology reflects the species’ adaptation to reef environments, with a relatively large first dorsal fin positioned slightly behind the pectoral fins. The second dorsal fin is much smaller and located directly above the anal fin. The pectoral fins are broad and slightly curved, providing excellent maneuverability in tight spaces between coral formations. The caudal fin displays the typical heterocercal structure of sharks, with the upper lobe being longer than the lower lobe.

The lateral line system is well-developed, consisting of sensory organs that detect water movement and pressure changes. This system proves particularly valuable in the complex three-dimensional environment of coral reefs, where visual detection of prey and predators may be limited. The ampullae of Lorenzini, electroreceptive organs concentrated around the head and snout, enable detection of electrical fields generated by living organisms, facilitating prey location even in murky water or at night.

Caribbean Reef Sharks exhibit sexual dimorphism, with males developing claspers (modified pelvic fins) for reproduction and typically maintaining a more slender build than females. Adult males rarely exceed 200 centimeters in length, while females can reach 250 centimeters or more. The species shows relatively slow growth rates compared to smaller shark species, with individuals requiring 12-15 years to reach sexual maturity.

Habitat & Distribution

The Caribbean Reef Shark inhabits the warm waters of the western Atlantic Ocean, with its distribution centered primarily in the Caribbean Sea and extending from southern Florida to northern South America. This species demonstrates a strong preference for coral reef environments, typically found at depths ranging from 1 to 65 meters (3 to 213 feet), though most encounters occur in waters less than 30 meters deep. The species shows remarkable fidelity to specific reef systems, with individual sharks often maintaining home ranges of several square kilometers within familiar coral formations.

Preferred habitats include fringing reefs, patch reefs, and reef walls where the complex topography provides hunting opportunities and shelter. Caribbean Reef Sharks frequently patrol reef edges where pelagic prey species venture close to the reef structure, creating productive feeding zones. The species also utilizes seagrass beds adjacent to coral reefs, particularly during juvenile stages when smaller prey species are more abundant in these nursery habitats.

Temperature preferences restrict Caribbean Reef Sharks to tropical and subtropical waters, with optimal conditions occurring between 24-28°C (75-82°F). This thermal requirement limits their distribution to the consistently warm waters of the Caribbean basin, unlike more widely distributed requiem sharks that tolerate greater temperature variations. Seasonal movements may occur in response to water temperature changes, prey availability, and reproductive cycles, though these movements typically remain within the broader Caribbean region.

The species demonstrates notable site fidelity, with acoustic tagging studies revealing that individual sharks may remain within specific reef areas for months or years. This behavior contrasts with more migratory shark species and reflects the relatively stable food resources available within established coral reef ecosystems. However, some individuals undertake longer movements between islands or along continental shelves, particularly during reproductive periods or in response to environmental changes.

Distribution patterns show higher densities around islands and continental shelf areas with extensive coral reef development, including the Bahamas, Lesser Antilles, and the continental shelves of Central and South America. The species appears less common in areas with degraded reef systems or where human fishing pressure has been intense, suggesting sensitivity to ecosystem health and fishing mortality.

Diet & Feeding Behavior

Caribbean Reef Sharks function as opportunistic predators with a diverse diet reflecting the rich biodiversity of coral reef ecosystems. Primary prey species include reef fish such as snappers, grunts, parrotfish, and surgeonfish, which constitute the bulk of their diet. The species also feeds extensively on rays, particularly small stingrays and electric rays that inhabit sandy areas adjacent to coral reefs. Crustaceans, including crabs and lobsters, provide additional nutritional resources, especially for juvenile sharks developing within seagrass nursery habitats.

Feeding behavior varies considerably based on time of day, with Caribbean Reef Sharks exhibiting increased activity during dawn and dusk periods when many prey species are most vulnerable. Nocturnal feeding appears particularly important, as the sharks’ enhanced sensory capabilities provide significant advantages over visually-oriented prey species in low-light conditions. The species employs various hunting strategies, from active pursuit of fast-moving fish to ambush tactics near coral formations and cleaning stations.

Seasonal variations in prey availability influence feeding patterns, with the sharks adapting their hunting strategies to exploit temporary abundance of specific prey species. During spawning aggregations of reef fish, Caribbean Reef Sharks may concentrate their feeding activities around these predictable food sources. Similarly, the species has been observed following feeding opportunities created by other predators, such as moray eels flushing prey from coral crevices.

The sharks’ broad, serrated teeth prove highly effective for processing a wide variety of prey sizes and types. Smaller prey items are typically swallowed whole, while larger fish and rays are bitten and consumed in sections. This feeding flexibility allows Caribbean Reef Sharks to exploit virtually any available protein source within their reef environment, from small juvenile fish to adult specimens approaching their own size.

Feeding rates appear to be influenced by water temperature, prey density, and individual metabolic requirements. Studies suggest that Caribbean Reef Sharks may feed every few days rather than daily, allowing for efficient energy utilization in the relatively food-rich coral reef environment. This feeding pattern differs from the more frequent feeding requirements of smaller, more active shark species with higher metabolic rates.

Behavior & Adaptations

Caribbean Reef Sharks display complex behavioral patterns that reflect their evolution as specialized reef predators. The species demonstrates remarkable site fidelity, with individual sharks establishing and maintaining defined home ranges within specific reef systems. This territorial behavior includes regular patrolling routes along reef edges, cleaning stations, and areas of high prey density. Acoustic tracking studies have revealed that many individuals return to the same resting areas and hunting grounds repeatedly, suggesting sophisticated spatial memory and navigation abilities.

Social behavior varies considerably among individuals and circumstances, with Caribbean Reef Sharks capable of both solitary and group activities. Small aggregations may form around abundant food sources or during cleaning activities at specific reef locations. However, the species generally maintains spacing between individuals outside of feeding contexts, suggesting a balance between competitive interactions and cooperative opportunities for accessing resources.

The sharks exhibit pronounced circadian activity patterns, with peak activity occurring during crepuscular periods when many prey species are most active. During daylight hours, Caribbean Reef Sharks often rest in deeper water or seek shelter within coral formations, reducing metabolic demands and avoiding potential predation pressure. This behavioral adaptation maximizes hunting efficiency while minimizing energy expenditure during periods of lower prey availability.

Cleaning behavior represents an important aspect of Caribbean Reef Shark ecology, with individuals regularly visiting cleaning stations where small fish remove parasites and dead tissue. These cleaning interactions demonstrate the species’ integration within broader reef community dynamics and provide opportunities for researchers to observe and study individual sharks repeatedly at predictable locations.

The species has evolved several anatomical adaptations for reef life, including enhanced maneuverability through broad pectoral fins and a relatively compact body plan compared to more pelagic shark species. The development of a robust lateral line system enables effective navigation through complex coral formations, while enhanced electroreception capabilities facilitate prey detection in the electrically noisy environment of active coral reefs.

Stress responses in Caribbean Reef Sharks include depth changes, increased swimming speed, and temporary abandonment of established territories when faced with unfamiliar stimuli. These behavioral adaptations may prove crucial for survival in increasingly human-impacted reef environments, though chronic stress from persistent disturbances could affect long-term health and reproductive success.

Reproduction & Life Cycle

Caribbean Reef Sharks exhibit a viviparous reproductive strategy, with females producing live young after an extended gestation period. Sexual maturity occurs relatively late in the species’ life cycle, with males reaching reproductive capability at approximately 12-15 years of age and females maturing slightly later at 15-20 years. This delayed maturity represents a significant life history constraint that affects population growth rates and recovery potential following exploitation.

The reproductive cycle follows a biennial pattern, with females producing litters every two years after successful mating. Gestation periods extend approximately 12 months, during which developing embryos receive nutrients through a placental connection to the mother. This extended developmental period allows for the production of relatively large, well-developed young that possess enhanced survival capabilities compared to egg-laying species.

Litter sizes typically range from 4-8 pups, with larger females generally producing more offspring. Newborn Caribbean Reef Sharks measure approximately 60-75 centimeters (24-30 inches) in length and possess the coloration and body proportions of miniature adults. The relatively large size of newborns reflects the species’ strategy of producing fewer, higher-quality offspring rather than large numbers of smaller, more vulnerable young.

Nursery habitats play crucial roles in early life history, with juvenile sharks typically inhabiting shallow seagrass beds and mangrove areas that provide protection from larger predators while offering abundant small prey. These nursery environments often occur in close proximity to adult reef habitats, facilitating eventual recruitment to adult populations. The species demonstrates strong site fidelity to nursery areas, with some individuals remaining in these protective environments for several years.

Mating behavior occurs within adult reef territories, typically during warmer months when water temperatures are optimal for embryonic development. Courtship involves complex behavioral displays, with males following females closely and engaging in gentle biting of the female’s pectoral fins and flanks. This pre-copulatory behavior may continue for several hours before actual mating occurs.

Growth rates are relatively slow compared to smaller shark species, with juveniles requiring 8-12 years to reach adult size. This extended juvenile period reflects the species’ adaptation to the stable, resource-rich environment of coral reefs, where rapid growth is less critical than developing effective hunting skills and territorial awareness. The combination of late maturity, extended gestation, and slow growth rates makes Caribbean Reef Shark populations particularly vulnerable to overexploitation and environmental disturbances.

Predators & Threats

Adult Caribbean Reef Sharks face limited natural predation due to their size and position as apex predators within coral reef ecosystems. However, juvenile sharks encounter predation pressure from larger sharks, including Bull Sharks (*Carcharhinus leucas*), Tiger Sharks (*Galeocerdo cuvier*), and other large carcharhinids that may venture into nursery habitats. Large grouper species and moray eels may also pose threats to very small juvenile Caribbean Reef Sharks, though such predation events are relatively uncommon.

The most significant threats to Caribbean Reef Shark populations stem from human activities, particularly commercial and recreational fishing operations. The species is frequently caught as bycatch in commercial fisheries targeting other species, with longline, gillnet, and trawl operations causing substantial mortality. Directed fishing for Caribbean Reef Sharks occurs in some areas, driven by demand for shark meat, fins, and other products in international markets.

Habitat degradation represents an increasingly serious threat to Caribbean Reef Shark populations throughout their range. Coral reef decline due to climate change, pollution, and coastal development directly impacts the species by reducing prey availability and eliminating essential habitat components. Ocean acidification and rising water temperatures associated with climate change pose additional stresses that may affect both the sharks and their prey species.

Tourism-related activities present complex challenges for Caribbean Reef Shark conservation. While shark diving operations can provide economic incentives for protection, poorly managed tourism may cause behavioral disruption and stress responses that affect feeding patterns and reproductive success. The provision of bait during shark diving activities has been documented to alter natural feeding behavior and spatial distribution patterns.

Pollution, particularly from agricultural runoff and coastal development, degrades water quality and may accumulate toxic compounds in shark tissues. Heavy metals, pesticides, and other contaminants can affect neurological function, reproductive success, and immune system efficiency. Plastic pollution represents an emerging threat, with sharks potentially ingesting plastic debris or consuming prey species that have accumulated plastic particles.

Overfishing of prey species can create indirect pressures on Caribbean Reef Shark populations by reducing food availability. The collapse of certain reef fish populations due to intensive fishing pressure may force sharks to expand their hunting ranges or alter their feeding behavior, potentially increasing energetic costs and reducing reproductive success.

Conservation Status

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) currently classifies the Caribbean Reef Shark as Near Threatened, reflecting growing concerns about population declines throughout the species’ range. This classification acknowledges the species’ vulnerability to fishing pressure and habitat degradation while recognizing that immediate extinction risk remains relatively low compared to more critically endangered shark species.

Population assessments indicate significant declines in Caribbean Reef Shark abundance across multiple locations, with some areas experiencing reductions of 50% or more over the past several decades. The Bahamas, where the species has received legal protection, maintains some of the healthiest remaining populations, while areas with intensive fishing pressure show more pronounced declines. These population trends reflect the species’ life history characteristics, which limit recovery potential following exploitation.

The species benefits from protection measures implemented in several Caribbean nations, including the establishment of marine protected areas and fishing restrictions. The Bahamas implemented a comprehensive shark sanctuary in 2011, prohibiting all commercial shark fishing within their territorial waters. Similar protection measures have been adopted in other Caribbean territories, though enforcement capabilities vary significantly among jurisdictions.

Regional conservation efforts focus on habitat protection, fishing regulation, and international cooperation to address migratory species management. The Caribbean Reef Shark’s relatively limited range facilitates coordinated conservation approaches, though political and economic differences among Caribbean nations complicate implementation of unified protection strategies.

Research priorities include population monitoring, habitat assessment, and evaluation of current protection measures’ effectiveness. Acoustic tagging studies provide valuable data on movement patterns and habitat use, while genetic analyses help identify distinct population units requiring specific conservation attention. These research efforts support evidence-based management decisions and help prioritize limited conservation resources.

The species’ importance for marine tourism provides economic incentives for conservation, with shark diving operations generating substantial revenue in several Caribbean locations. This economic value helps build local support for protection measures and demonstrates the financial benefits of maintaining healthy shark populations compared to short-term exploitation.

Climate change adaptation strategies become increasingly important for Caribbean Reef Shark conservation, as rising water temperatures and ocean acidification threaten the coral reef ecosystems upon which the species depends. Conservation planning must consider these long-term environmental changes and their potential impacts on both shark populations and their prey species.

Human Interaction

Caribbean Reef Sharks maintain generally peaceful relationships with humans, rarely displaying aggressive behavior toward divers or swimmers. The species’ reputation as a docile reef shark has made it popular among recreational divers, contributing to substantial marine tourism revenue throughout the Caribbean region. Professional dive operators frequently encounter Caribbean Reef Sharks during routine reef diving activities, with the sharks typically displaying curious but non-threatening behavior toward human visitors.

Commercial fishing operations represent the primary form of human interaction with Caribbean Reef Sharks, though rarely as a target species. The sharks are commonly caught as bycatch in fisheries targeting snappers, groupers, and other reef fish species. Longline fishing operations pose particular threats, as Caribbean Reef Sharks readily take baited hooks intended for other species. Traditional fishing methods, including handlines and fish traps, also result in occasional captures.

Shark diving tourism has emerged as a significant economic activity in several Caribbean destinations, with operators specifically seeking encounters with Caribbean Reef Sharks. These operations typically involve controlled feeding situations where sharks are attracted to dive sites using bait, allowing tourists to observe and photograph the animals at close range. While such activities generate important economic benefits for local communities, they also raise concerns about behavioral modification and dependency on artificial food sources.

The species appears in local folklore and cultural traditions throughout the Caribbean, often regarded with respect rather than fear. Traditional fishing communities have coexisted with Caribbean Reef Sharks for centuries, developing fishing practices that generally avoid unnecessary shark mortality. However, changing economic conditions and increased fishing pressure have altered these traditional relationships in many areas.

Scientific research involving Caribbean Reef Sharks includes tagging studies, behavioral observations, and population assessments conducted by marine biologists and conservation organizations. These research activities provide crucial data for conservation planning while involving local communities in citizen science programs. The species’ predictable behavior and site fidelity make it particularly suitable for long-term research studies.

Educational programs featuring Caribbean Reef Sharks help promote marine conservation awareness and build support for protection measures. School programs, public aquarium displays, and community outreach activities use the species’ charismatic appeal to teach broader lessons about coral reef ecology and conservation. These educational efforts prove particularly effective in Caribbean communities where residents have direct experience with the species.

The growing recognition of Caribbean Reef Sharks’ ecological and economic importance has led to increased collaboration between conservation organizations, tourism operators, and local governments. This cooperation focuses on developing sustainable management practices that balance economic benefits with conservation needs, ensuring that future generations can continue to benefit from healthy shark populations.

Interesting Facts

Caribbean Reef Sharks possess an extraordinary ability to detect electrical fields as weak as 0.01 microvolts, allowing them to locate hidden prey even when buried in sand or concealed within coral crevices. This electroreception capability proves so sensitive that the sharks can detect the electrical activity of a fish’s gills from several feet away, providing a significant hunting advantage in the complex environment of coral reefs.

The species demonstrates remarkable site fidelity, with some individuals returning to the same resting spots and hunting territories for decades. Researchers have documented individual Caribbean Reef Sharks using identical daytime resting areas for over 10 years, suggesting sophisticated spatial memory capabilities that rival those of much more complex vertebrates. This behavior indicates that established adult sharks develop intimate knowledge of their reef territories that may take years to acquire.

Unlike many shark species that must swim continuously to breathe, Caribbean Reef Sharks can rest motionless on the sea floor while pumping water over their gills. This adaptation allows them to conserve energy during inactive periods while remaining alert to feeding opportunities. The ability to rest while maintaining respiratory function represents an important advantage in the energy-efficient lifestyle required for success in coral reef environments.

Caribbean Reef Sharks exhibit individual personality differences, with some individuals displaying consistently bold behavior while others remain more cautious in identical situations. These personality traits appear to remain stable over extended periods and may influence feeding success, territorial behavior, and survival rates. Such individual variation demonstrates the complex behavioral capabilities of these predators beyond simple instinctual responses.

The species possesses a unique adaptation for processing hard-shelled prey, with jaw muscles capable of generating bite forces exceeding 1,000 pounds per square inch. This crushing power allows Caribbean Reef Sharks to consume heavily armored prey such as spiny lobsters and large crabs that would be inaccessible to many other reef predators. The combination of cutting teeth and powerful jaw muscles makes them one of the most versatile predators in Caribbean reef ecosystems.

Recent studies have revealed that Caribbean Reef Sharks may live considerably longer than previously thought, with some individuals potentially reaching ages of 40-50 years. This longevity, combined with their slow reproductive rate, means that individual sharks may contribute to population stability for decades, making the loss of adult breeding individuals particularly significant for population recovery.

The species displays remarkable learning abilities, with individual sharks adapting their behavior based on experience with human activities. Some sharks have learned to associate the sound of boat engines with feeding opportunities at dive sites, while others have developed avoidance behaviors in response to fishing pressure. This behavioral flexibility suggests cognitive capabilities that allow rapid adaptation to changing environmental conditions.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Caribbean Reef Sharks dangerous to humans?

Caribbean Reef Sharks are generally not dangerous to humans and are considered one of the more docile shark species. They rarely display aggressive behavior toward divers or swimmers, and documented attacks are extremely rare. The species typically shows curiosity rather than aggression when encountering humans, making them popular among recreational divers. However, like all wild animals, they should be treated with respect and appropriate caution, particularly during feeding activities or when protecting young.

How can you distinguish Caribbean Reef Sharks from other similar species?

Caribbean Reef Sharks can be identified by their robust build, broad rounded snout, and gray-brown coloration with lighter underside. They lack the distinctive markings found on Blacktip Sharks and are stockier than the more streamlined Nurse Sharks. The first dorsal fin is relatively large and positioned behind the pectoral fins, while the second dorsal fin is much smaller. Their preference for shallow reef environments and typical size range of 6-8 feet also help distinguish them from other Caribbean shark species.

What is the best time and place to see Caribbean Reef Sharks?

Caribbean Reef Sharks are most active during dawn and dusk periods, making these optimal times for observation. They frequent coral reefs, reef walls, and adjacent sandy areas at depths of 10-100 feet throughout the Caribbean Sea. Popular viewing locations include the Bahamas, Belize, and various Caribbean islands where marine protected areas maintain healthy populations. Many dive operators offer shark diving experiences where these sharks can be observed reliably at established feeding sites.

How do Caribbean Reef Sharks contribute to coral reef ecosystem health?

As apex predators, Caribbean Reef Sharks play crucial roles in maintaining coral reef ecosystem balance by controlling populations of herbivorous and predatory fish species. They help prevent overgrazing of algae-eating fish that could otherwise damage coral formations, while also regulating populations of smaller predators that might otherwise overconsume juvenile reef fish. Their presence indicates a healthy reef ecosystem, and their removal often leads to cascading effects that can destabilize entire reef communities.

Conclusion

The Caribbean Reef Shark represents a cornerstone species within coral reef ecosystems, serving as both apex predator and indicator of marine ecosystem health throughout the Caribbean basin. As human pressures continue to impact these vital marine environments, the conservation of Caribbean Reef Sharks becomes increasingly critical for maintaining the biodiversity and ecological integrity of coral reef systems that support millions of people economically and culturally across the region.

Share The Article:

More Fish Species:

-

Bolivian Ram

The Bolivian Ram (Mikrogeophagus altispinosus) stands as one of South America’s most captivating cichlid species, representing a prime example…

-

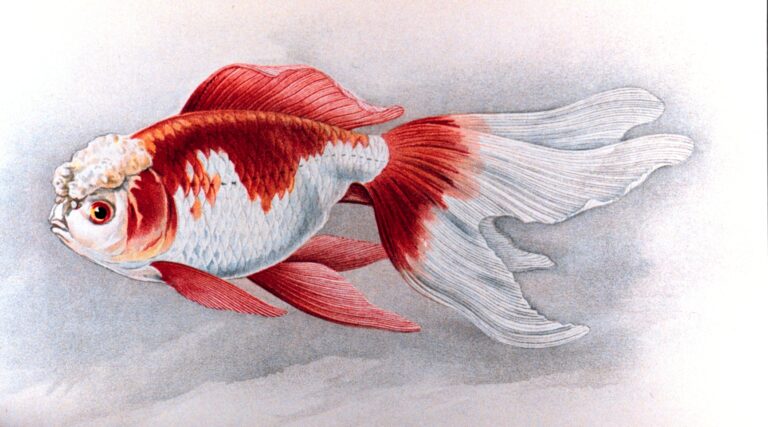

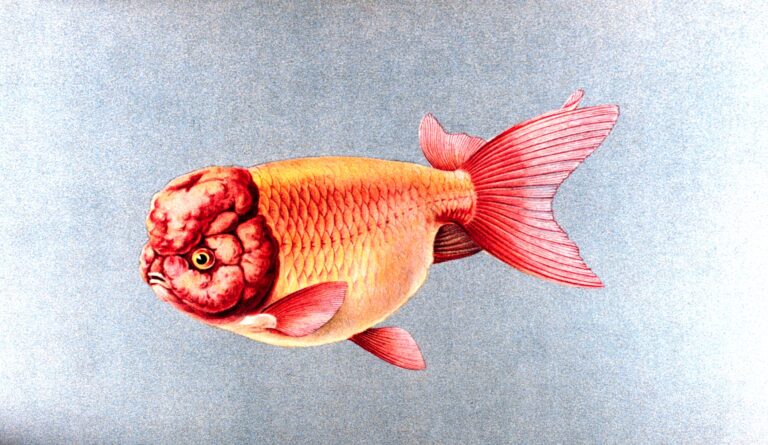

Oranda Goldfish

The Oranda Goldfish (Carassius auratus) stands as one of the most distinctive and cherished varieties in the world of…

-

Channel Catfish

The Channel Catfish stands as one of North America’s most recognizable and economically important freshwater fish species. Known scientifically…

-

Killifish

Killifish represent one of the most diverse and ecologically significant groups of small freshwater and brackish water fish, comprising…

-

Delta Tail Betta

The Delta Tail Betta (Betta splendens) represents one of the most recognizable and sought-after varieties within the aquarium trade,…

-

Rummy Nose Tetra

The Rummy Nose Tetra stands as one of the most distinctive and recognizable small freshwater fish species in South…

Discover

-

Crappie Fishing Guide for Beginners | 2025

Crappie fishing might just be one of the most rewarding experiences for new anglers. These popular panfish are abundant,…

-

How to Fish for Bluegill: 2025 Complete Guide

Bluegill might not be the biggest fish in the pond, but they sure make up for it in fight…

-

7 Best Family-Friendly Fishing Destinations in the U.S. (Tested with Kids!)

I still remember the first time I took my son Tommy fishing. He was five, armed with a Spider-Man…

-

5 Deadly Trolling Tactics Big Fish Can’t Resist

The first time I watched a 40-pound king salmon completely ignore my perfect trolling setup, I wanted to throw…

-

Reading Water Temperature: Seasonal Cues for Better Fishing

I’ve spent more mornings than I can count staring at a thermometer clipped to my fishing line, watching those…

-

Fly Fishing in the UK: Top Rivers and Seasonal Patterns

After nearly three decades casting flies across waters from Michigan to Maine – and now spending several weeks each…

Discover

-

Ranchu Goldfish

The Ranchu Goldfish represents one of the most distinctive and culturally significant ornamental fish varieties in the aquatic world….

-

Dalmatian Molly

The Dalmatian Molly stands as one of the most recognizable and beloved freshwater aquarium fish, distinguished by its striking…

-

Lemon Tetra

The Lemon Tetra (*Hyphessobrycon pulchripinnis*) stands as one of South America’s most vibrant freshwater fish species, distinguished by its…

-

Lionhead Goldfish

The Lionhead Goldfish represents one of the most distinctive and cherished ornamental varieties within the goldfish family, captivating aquarists…

-

King Mackerel Fishing: Top Strategies for Landing Smokers

Some days on the water just stick with you. Few things compare to that first time a king mackerel…

-

Whale Shark

The whale shark (*Rhincodon typus*) stands as the ocean’s largest fish species, representing one of nature’s most remarkable gentle…