Blue Shark

By Ryan Maron | Last Modified: July 3, 2025

The Blue Shark (Prionace glauca) represents one of the ocean’s most accomplished travelers, traversing entire ocean basins in epic migrations that span thousands of miles. This pelagic predator serves as a critical component of marine ecosystems worldwide, functioning as both predator and prey in complex oceanic food webs. Found in virtually every ocean, the Blue Shark’s streamlined body and remarkable swimming efficiency make it one of the most widely distributed sharks on Earth. Its ecological importance extends beyond simple predation, as it helps maintain the delicate balance of oceanic ecosystems while serving as an indicator species for ocean health. The species faces mounting pressure from commercial fishing operations, making its conservation status a matter of international concern for marine biologists and fisheries managers.

| Feature | Details |

| Common Name | Blue Shark |

| Scientific Name | Prionace glauca |

| Family | Carcharhinidae |

| Typical Size | 200-300 cm (6.5-10 ft), 27-55 kg (60-120 lbs) |

| Habitat | Open ocean, pelagic waters |

| Diet | Opportunistic carnivore |

| Distribution | Global, temperate and tropical waters |

| Conservation Status | Near Threatened (IUCN) |

Taxonomy & Classification

The Blue Shark belongs to the family Carcharhinidae, commonly known as requiem sharks, which includes some of the most successful and widespread shark species in the world. First described by Carl Linnaeus in 1758, Prionace glauca stands as the sole representative of the genus Prionace, distinguishing it from its relatives through unique anatomical and behavioral characteristics. The species name “glauca” derives from the Greek word for blue-gray, directly referencing the distinctive coloration that makes this shark instantly recognizable.

Within the broader taxonomic hierarchy, the Blue Shark represents a highly specialized branch of the carcharhinid family tree. Molecular studies have revealed that Prionace diverged from other requiem sharks approximately 50-60 million years ago, developing the streamlined body plan and enhanced swimming capabilities that define the species today. This evolutionary specialization for pelagic life has resulted in morphological features that distinguish Blue Sharks from their more coastal relatives.

The taxonomic classification reflects the species’ evolutionary adaptations to open ocean environments. Unlike many requiem sharks that exhibit strong regional variations, Blue Sharks show remarkable genetic uniformity across their global range, suggesting recent rapid expansion and high gene flow between populations. This genetic homogeneity supports the current single-species classification, though ongoing research continues to examine potential subspecies within different ocean basins.

Physical Description

The Blue Shark exhibits a perfectly streamlined body design that epitomizes pelagic adaptation. Adult specimens typically measure 200-300 centimeters in length, with females growing significantly larger than males. The most striking feature is the brilliant blue coloration that gives the species its common name, ranging from deep indigo on the dorsal surface to bright white on the ventral side. This counter-shading provides excellent camouflage in open water, making the shark nearly invisible when viewed from above or below.

The head profile shows distinct characteristics that separate Blue Sharks from other requiem species. The snout is notably long and pointed, measuring approximately 15-20% of the total body length. Large, circular eyes provide excellent vision in the dimly lit pelagic environment, while the mouth contains multiple rows of triangular, serrated teeth perfectly adapted for grasping slippery prey. The upper teeth are broader and more triangular, while the lower teeth are narrower and more pointed.

The fin structure reflects the species’ commitment to efficient swimming. The pectoral fins are exceptionally long and narrow, extending well beyond the head length and providing the lift necessary for the shark’s characteristic gliding swimming style. The first dorsal fin is positioned relatively far back on the body, while the second dorsal fin is quite small. The caudal fin displays the typical heterocercal shape of active sharks, with the upper lobe significantly longer than the lower lobe.

Sexual dimorphism becomes apparent in mature individuals, with males developing enlarged claspers and females showing broader body proportions. The skin texture is relatively smooth compared to other sharks, with small dermal denticles that minimize drag during swimming. This smooth skin, combined with the streamlined body shape, contributes to the Blue Shark’s reputation as one of the most efficient swimmers in the ocean.

Habitat & Distribution

Blue Sharks inhabit the open ocean waters of virtually every temperate and tropical sea, making them one of the most widely distributed shark species on Earth. Their range extends from approximately 50°N to 50°S latitude, encompassing the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans. These sharks prefer the epipelagic zone, typically remaining within the upper 200 meters of the water column where prey density is highest and temperature conditions are most favorable.

The species shows a strong preference for specific water temperatures, generally remaining within the 12-20°C range, though they can tolerate temperatures from 7-25°C. This temperature preference drives much of their migratory behavior, as Blue Sharks follow thermal fronts and seasonal temperature changes across ocean basins. They are commonly found along continental shelf edges, underwater ridges, and upwelling areas where nutrient-rich waters support abundant prey populations.

Oceanic currents play a crucial role in Blue Shark distribution patterns. The species utilizes major current systems for long-distance migration, with individuals tracked covering distances exceeding 5,000 kilometers in a single year. The Gulf Stream in the Atlantic and the Kuroshio Current in the Pacific serve as major highways for Blue Shark movement, facilitating their transoceanic migrations.

Depth preferences vary with geographic location, time of day, and prey availability. While primarily surface-dwelling, Blue Sharks regularly dive to depths of 350 meters and have been recorded at depths exceeding 750 meters. These vertical migrations often correspond with the daily movements of prey species, particularly squid and small pelagic fish that migrate between surface waters and deeper layers.

The global distribution of Blue Sharks reflects their remarkable adaptability to diverse oceanic conditions. From the cold waters off Newfoundland to the warm tropical seas of the Indo-Pacific, these sharks have colonized virtually every available pelagic habitat. However, they generally avoid polar waters and enclosed seas, preferring the open ocean environment where their swimming efficiency provides the greatest advantage.

Diet & Feeding Behavior

The Blue Shark functions as an opportunistic predator with a diverse diet that reflects the patchy nature of prey distribution in the open ocean. Squid comprises the largest portion of their diet, often accounting for 60-80% of stomach contents in analyzed specimens. The species shows particular preference for pelagic cephalopods, including species from the families Ommastrephidae and Cranchiidae, which are abundant in oceanic waters.

Small pelagic fish represent the second major component of Blue Shark diet. Schools of herring, sardines, anchovies, and mackerel provide concentrated feeding opportunities, particularly during seasonal migrations when prey density reaches peak levels. The sharks’ ability to locate and exploit these schooling events demonstrates their sophisticated sensory capabilities and behavioral adaptations to pelagic hunting.

Feeding behavior varies significantly with prey type and availability. When hunting squid, Blue Sharks often employ a slow, methodical approach, using their excellent vision to locate individual prey items in the water column. Their long pectoral fins allow them to glide effortlessly through the water while scanning for feeding opportunities. When encountering fish schools, their behavior becomes more aggressive, with rapid acceleration and coordinated attacks that can scatter entire schools.

The species exhibits both diurnal and nocturnal feeding patterns, with activity levels often synchronized to the vertical migrations of prey species. During daylight hours, Blue Sharks may descend to deeper waters following squid populations, while nighttime feeding often occurs near the surface where many prey species migrate to feed on plankton. This behavioral flexibility allows them to exploit the full range of available prey resources.

Scavenging behavior represents another important aspect of Blue Shark feeding ecology. The species readily feeds on dead and dying fish, marine mammals, and other organic matter encountered in the open ocean. This scavenging behavior provides an important energy source in the nutrient-poor pelagic environment and helps explain their ability to survive in areas where active prey may be scarce.

Behavior & Adaptations

Blue Sharks exhibit remarkable behavioral adaptations that enable them to thrive in the challenging pelagic environment. Their most notable behavioral characteristic is their extraordinary migration capability, with individual sharks traveling distances that span entire ocean basins. Satellite tracking studies have documented movements exceeding 9,000 kilometers, making them among the most mobile vertebrates on Earth.

The species’ swimming behavior reflects their specialization for energy-efficient travel. Blue Sharks employ a distinctive swimming style that maximizes forward momentum while minimizing energy expenditure. Their long pectoral fins function as hydroplanes, providing lift and stability during extended gliding phases. This efficient swimming technique allows them to cover vast distances while searching for prey in the relatively barren oceanic environment.

Social behavior in Blue Sharks appears to be more complex than previously understood. While generally considered solitary animals, they occasionally form loose aggregations around concentrated food sources or during reproductive periods. These aggregations may involve hundreds of individuals and can persist for several weeks. The social structure within these groups appears to be based on size, with larger individuals dominating prime feeding positions.

Thermoregulatory behavior represents another crucial adaptation to pelagic life. Although Blue Sharks lack the specialized heat-retention systems found in some other shark species, they exhibit behavioral thermoregulation through habitat selection and swimming patterns. They actively seek out optimal thermal conditions, often remaining within specific temperature ranges that maximize metabolic efficiency.

The species demonstrates remarkable navigation abilities, with individuals showing strong site fidelity to specific feeding areas despite traveling thousands of kilometers between visits. This navigation capability likely involves a combination of magnetic field detection, chemical cues, and celestial navigation, though the exact mechanisms remain under investigation.

Defensive behaviors include rapid escape responses when threatened and the ability to dive to considerable depths when pursued. Blue Sharks can achieve burst speeds exceeding 35 kilometers per hour, though they typically cruise at much slower speeds to conserve energy. Their streamlined body shape and powerful tail provide excellent acceleration capabilities when needed.

Reproduction & Life Cycle

Blue Sharks exhibit a complex reproductive strategy that reflects their pelagic lifestyle and global distribution. Sexual maturity is reached at different ages depending on geographic location and environmental conditions, with males typically maturing at 4-6 years and females at 5-7 years. Size at maturity ranges from 180-220 centimeters for males and 200-250 centimeters for females.

The species follows a viviparous reproductive mode, with females giving birth to live young after an extended gestation period. Mating typically occurs during spring and summer months in temperate waters, with specific timing varying by geographic region. The mating process involves complex courtship behaviors and can be quite aggressive, with males often inflicting bite wounds on females during copulation.

Gestation periods in Blue Sharks are among the longest recorded for any shark species, lasting 9-12 months depending on environmental conditions. This extended development period allows for the production of relatively large, well-developed young that have a better chance of survival in the challenging pelagic environment. Litter sizes are highly variable, ranging from 4-135 pups, with an average of 25-50 individuals per litter.

Pupping grounds are typically located in warmer waters, often near continental shelves or oceanic islands where prey density is higher and predation pressure may be reduced. Females show strong site fidelity to specific pupping areas, returning to the same regions year after year. The young are born at approximately 35-44 centimeters in length and are immediately capable of independent swimming and feeding.

Juvenile Blue Sharks face significant mortality during their first year of life, with survival rates estimated at 10-30% depending on environmental conditions and predation pressure. Those that survive the juvenile stage grow rapidly, reaching adult size within 4-6 years. The species’ reproductive output is relatively low compared to other sharks, making populations vulnerable to overexploitation.

Growth rates vary significantly with geographic location and food availability. In nutrient-rich areas, Blue Sharks may grow 20-30 centimeters per year during their first few years of life. Growth rates decrease substantially after sexual maturity is reached, with adult growth rates typically 5-10 centimeters per year. Maximum reported size exceeds 400 centimeters, though individuals over 350 centimeters are increasingly rare.

Predators & Threats

Adult Blue Sharks face relatively few natural predators due to their large size and open ocean habitat, though several species pose threats to different life stages. Large pelagic predators including killer whales, larger sharks such as great whites and tiger sharks, and giant Pacific octopi have been documented attacking Blue Sharks. Juvenile individuals face additional predation pressure from a wider range of species, including billfish, tuna, and other large pelagic fish.

The primary threat to Blue Shark populations comes from commercial fishing operations, both targeted and incidental. The species is heavily exploited for its fins, which are highly valued in international markets for shark fin soup. Their slow growth rate and late sexual maturity make Blue Shark populations particularly vulnerable to overfishing pressure. Annual catches are estimated to exceed 10 million individuals globally, making them one of the most heavily harvested shark species.

Longline fishing operations pose the greatest threat to Blue Shark populations. These fisheries, targeting tuna and swordfish, result in massive bycatch of Blue Sharks across their range. While some individuals are released alive, post-release mortality rates are significant, particularly for sharks that have been deeply hooked or brought to the surface from considerable depths. The global extent of longline fishing means that virtually no Blue Shark population remains unexploited.

Climate change represents an emerging threat to Blue Shark populations through its effects on ocean temperature, current patterns, and prey distribution. Changes in thermal structure may alter migration routes and feeding areas, while ocean acidification could impact prey species abundance. The species’ reliance on specific temperature ranges makes them particularly vulnerable to rapid climate changes.

Pollution poses additional challenges for Blue Shark populations. Heavy metals, persistent organic pollutants, and plastic debris accumulate in their tissues through bioaccumulation up the food chain. Microplastics have been found in Blue Shark stomach contents, though the long-term effects of plastic ingestion remain unclear. Chemical pollution may affect reproductive success and immune system function.

Marine habitat degradation affects Blue Shark populations indirectly through impacts on prey species. Overfishing of small pelagic fish and squid reduces available food resources, while coastal development and pollution can impact nursery areas. The cumulative effects of multiple stressors create complex challenges for Blue Shark conservation.

Conservation Status

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) currently lists the Blue Shark as Near Threatened on the Red List of Threatened Species, though this classification may not fully reflect the species’ precarious situation in many regions. Recent stock assessments suggest that several regional populations have declined by 50-80% over the past three decades, with the most dramatic declines occurring in the North Atlantic and North Pacific.

The species’ conservation status is complicated by its highly migratory nature and the lack of comprehensive population data across its global range. While some regions may maintain relatively stable populations, others show clear signs of overfishing and population decline. The Mediterranean Sea population is considered particularly vulnerable, with evidence suggesting severe depletion compared to historical levels.

International conservation efforts have begun to address Blue Shark exploitation, though progress remains limited. The species was recently added to Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), requiring permits for international trade. However, enforcement of these regulations remains challenging given the global nature of shark fin trade and the difficulty of species identification in processed products.

Regional fisheries management organizations have implemented various conservation measures, including catch limits, retention bans, and gear modifications designed to reduce bycatch mortality. The effectiveness of these measures varies significantly between regions, with some areas showing modest improvements while others continue to experience population declines. The European Union has prohibited the retention of Blue Sharks in certain fisheries, while other regions have implemented minimum size limits.

Scientific research continues to provide crucial data for conservation planning. Satellite tagging studies have revealed the extent of Blue Shark movements and helped identify critical habitats and migration corridors. Genetic studies are examining population structure and connectivity, providing insights into the appropriate scale for management actions. Age and growth studies are refining our understanding of the species’ life history and vulnerability to exploitation.

The challenge of conserving Blue Sharks illustrates the broader difficulties of managing highly migratory species in international waters. Effective conservation requires coordinated international action, improved monitoring of fishing activities, and stronger enforcement of existing regulations. The species’ ecological importance as a top predator makes their conservation critical for maintaining healthy ocean ecosystems.

Human Interaction

Blue Sharks have a complex relationship with human activities, ranging from commercial exploitation to recreational fishing and ecotourism. Commercial fisheries represent the most significant human interaction, with Blue Sharks being one of the most heavily harvested shark species globally. Their fins are highly valued in Asian markets, while their meat is used for food in various cultures, though it is often considered lower quality compared to other shark species.

Recreational fishing for Blue Sharks has become increasingly popular, particularly in regions where the species is abundant near the surface. Sport fishing operations target Blue Sharks for their fighting ability and the challenge they present to anglers. Many recreational fisheries now practice catch-and-release techniques, though the survival rates of released sharks vary depending on handling methods and hook placement.

The species plays an important role in emerging shark diving and ecotourism industries. Blue Sharks’ relatively docile nature and predictable behavior make them suitable for supervised diving encounters in several locations worldwide. These activities provide economic incentives for conservation while raising public awareness about shark conservation issues. The Azores, California, and South Africa have developed successful Blue Shark diving operations.

Attacks on humans by Blue Sharks are extremely rare, with only a handful of confirmed cases in recorded history. Most incidents involve cases of mistaken identity or situations where humans have entered the water near fishing operations where blood and bait have attracted sharks. The species’ preference for open ocean habitats means that encounters with humans are naturally limited.

Blue Sharks occasionally interact with shipping and naval activities, with individuals sometimes following vessels for extended periods. This behavior may be related to food opportunities created by ship operations or the acoustic signatures of vessels. Military sonar operations have raised concerns about potential impacts on Blue Shark behavior and navigation abilities.

The species has cultural significance in various maritime communities, appearing in folklore, art, and literature. Their distinctive appearance and wide distribution have made them recognizable symbols of ocean wildlife. In some cultures, Blue Sharks are considered indicators of ocean health and weather patterns, with their presence or absence interpreted as signs of environmental change.

Research activities represent another important aspect of human interaction with Blue Sharks. Scientists have tagged thousands of individuals to study their movements, behavior, and population dynamics. This research has provided crucial insights into the species’ ecology and has informed conservation efforts. Collaborative research programs involving commercial fishermen have improved our understanding of Blue Shark distribution and abundance.

Interesting Facts

Blue Sharks possess several remarkable characteristics that distinguish them from other shark species. Their extraordinary migration capabilities make them among the most traveled animals on Earth, with some individuals covering distances equivalent to traveling from New York to London twice in a single year. These epic journeys often follow complex routes that span multiple ocean basins and can take several years to complete.

The species demonstrates exceptional swimming efficiency, capable of maintaining steady speeds of 25-35 kilometers per hour for extended periods. Their streamlined body design and specialized fin structure allow them to cover vast distances while expending minimal energy. This efficiency is so remarkable that engineers have studied Blue Shark swimming mechanics to improve underwater vehicle design.

Blue Sharks exhibit sophisticated sensory capabilities that enable them to navigate across featureless ocean expanses. They can detect electrical fields as weak as 0.005 microvolts per centimeter, allowing them to sense the bioelectric fields produced by other organisms. This ability helps them locate prey in the vast pelagic environment where visual cues may be limited.

The species shows remarkable adaptability to different oceanic conditions, with individuals able to tolerate temperature changes of 10-15°C during their migrations. This thermal tolerance allows them to exploit a wide range of habitats and follow prey species across different water masses. Their ability to adjust their metabolic rate based on water temperature helps them maintain energy balance during long migrations.

Blue Sharks have been observed engaging in complex social behaviors that challenge traditional views of shark intelligence. They have been documented following fishing vessels for days, apparently learning to associate human activities with feeding opportunities. Some individuals show recognition of specific boats and crew members, suggesting higher cognitive abilities than previously recognized.

The species plays a crucial role in oceanic nutrient cycling, transporting nutrients across vast distances through their migrations. When Blue Sharks feed in nutrient-rich upwelling areas and then migrate to nutrient-poor oceanic regions, they effectively transport organic matter and energy across ocean basins. This ecological function makes them important components of global ocean productivity.

Blue Sharks have been recorded diving to depths exceeding 1,000 meters, far deeper than their typical habitat range. These deep dives may be related to foraging behavior, predator avoidance, or thermoregulation. The physiological adaptations that allow them to handle such extreme depth changes while maintaining their surface-oriented lifestyle remain poorly understood.

The species exhibits remarkable longevity, with some individuals estimated to live over 30 years. This extended lifespan, combined with their late sexual maturity, contributes to their vulnerability to overexploitation. Age determination in Blue Sharks requires specialized techniques, as traditional methods used for other fish species are often unreliable for this species.

Conclusion

The Blue Shark stands as one of the ocean’s most remarkable species, representing the pinnacle of pelagic adaptation through millions of years of evolution. Their role as oceanic wanderers makes them essential components of marine ecosystems worldwide, contributing to nutrient cycling and maintaining the balance of oceanic food webs. However, their conservation status reflects the broader challenges facing marine predators in an increasingly exploited ocean, making their protection crucial for maintaining healthy marine ecosystems and preserving one of nature’s most accomplished travelers for future generations.

Share The Article:

More Fish Species:

-

Crown Tail Betta

The Crown Tail Betta stands as one of aquaculture’s most distinctive ornamental fish, renowned for its dramatically elongated, spiky…

-

Marigold Swordtail

The Marigold Swordtail (Xiphophorus hellerii var. marigold) stands as one of the most vibrant and sought-after color variants within…

-

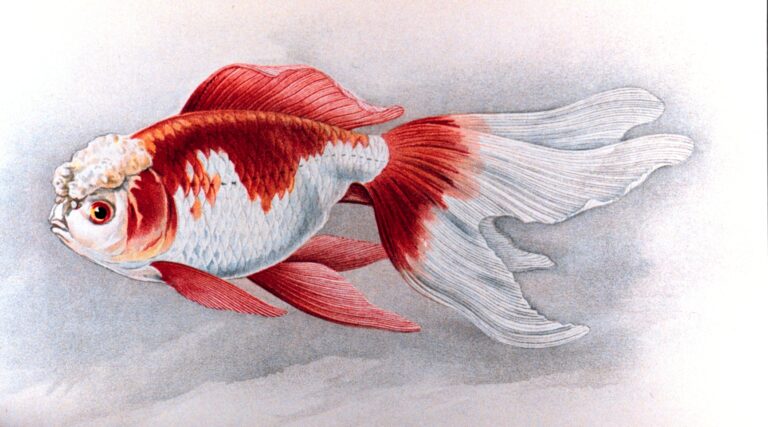

Oranda Goldfish

The Oranda Goldfish (Carassius auratus) stands as one of the most distinctive and cherished varieties in the world of…

-

Wagtail Platy

The Wagtail Platy stands as one of the most distinctive and beloved freshwater aquarium fish, renowned for its elegant…

-

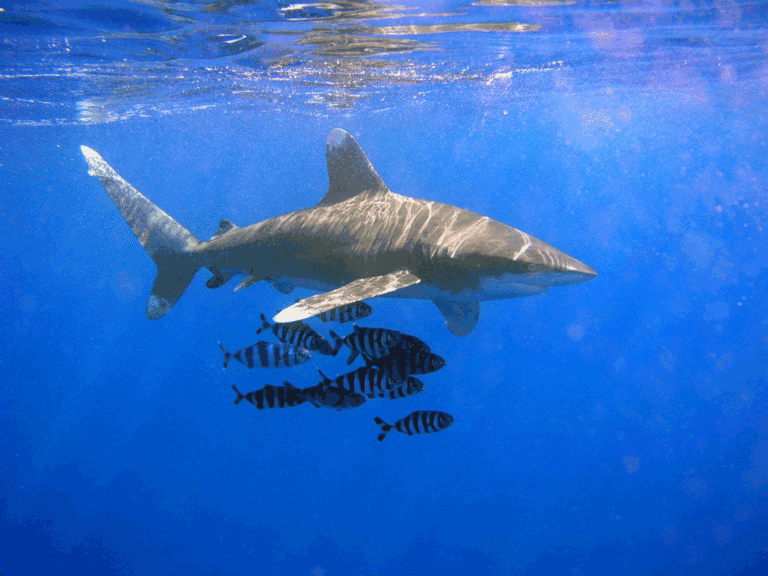

Oceanic Whitetip Shark

The Oceanic Whitetip Shark (*Carcharhinus longimanus*) stands as one of the ocean’s most formidable and recognizable apex predators, distinguished…

-

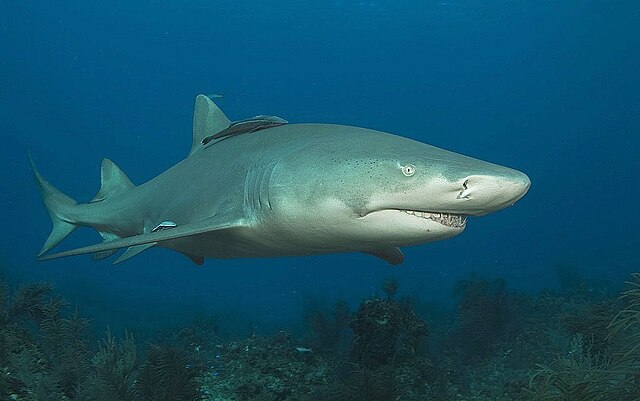

Bull Shark

The Bull Shark represents one of the most formidable apex predators in marine ecosystems worldwide. Known scientifically as Carcharhinus…

Discover

-

Dusky Shark

The Dusky Shark represents one of the most ecologically significant yet vulnerable large predators inhabiting coastal and pelagic waters…

-

7 Best Fly Fishing Foods That Trout Can’t Resist in 2025

If there’s one thing I’ve learned after three decades of fly fishing, it’s that trout can be maddeningly selective…

-

Lemon Shark

The Lemon Shark (*Negaprion brevirostris*) represents one of the most scientifically studied and ecologically significant predators in coastal marine…

-

Fly Fishing vs Spinning Reels: Choosing the Right Technique

If there’s one debate that never seems to end in fishing circles, it’s fly fishing versus spinning gear. I’ve…

-

Utah Fishing License Guide: Costs, Requirements & Hidden Tips for 2025

When I first planned a fishing trip to Utah’s beautiful waters about a decade ago, figuring out the licensing…

-

Bigeye Thresher Shark

The Bigeye Thresher Shark represents one of the ocean’s most extraordinary predators, distinguished by its dramatically elongated tail fin…

Discover

-

Yellowfin VS Bluefin Tuna: Which Should You Target? (Expert Guide)

Let’s be honest – the first time I saw a yellowfin and bluefin tuna side by side at the…

-

Spotted Bass

The Spotted Bass (Micropterus punctulatus) stands as one of North America’s most distinctive freshwater game fish, renowned for its…

-

Bubble Eye Goldfish

The Bubble Eye Goldfish stands as one of the most distinctive and recognizable varieties of ornamental goldfish, captivating aquarists…

-

Zebra Danio

The Zebra Danio (Danio rerio) stands as one of freshwater aquarium keeping’s most recognizable and scientifically significant species. This…

-

Discus Fish

The Discus Fish (Symphysodon spp.) stands as one of the most revered species in the freshwater aquarium trade, earning…

-

Pelagic Thresher Shark

The Pelagic Thresher Shark stands as one of the ocean’s most distinctive and efficient predators, renowned for its dramatically…