Pacu Fish

By Ryan Maron | Last Modified: June 8, 2025

Pacu fish represent one of South America’s most ecologically significant freshwater species, encompassing several closely related members of the subfamily Serrasalminae. These robust, herbivorous characins, scientifically classified under genera such as Piaractus, Colossoma, and Mylossoma, play crucial roles as seed dispersers and primary consumers in Amazonian aquatic ecosystems. Despite their superficial resemblance to their carnivorous piranha relatives, Pacu fish have evolved specialized feeding adaptations that make them essential components of Neotropical river systems. Their economic importance extends beyond their native range, as these species support substantial aquaculture operations and recreational fisheries throughout tropical regions worldwide.

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Common Name | Pacu Fish |

| Scientific Name | Piaractus spp., Colossoma spp., Mylossoma spp. |

| Family | Serrasalmidae |

| Typical Size | 30-108 cm, 2-40 kg |

| Habitat | Tropical freshwater rivers and floodplains |

| Diet | Omnivorous (primarily frugivorous) |

| Distribution | Amazon and Orinoco basins, introduced globally |

| Conservation Status | Least Concern to Data Deficient |

Taxonomy & Classification

The taxonomic classification of Pacu fish reflects their evolutionary relationship within the diverse Serrasalmidae family. These species belong to the subfamily Serrasalminae, which they share with their more notorious piranha relatives. The primary genera encompassing true Pacu fish include Piaractus, containing species such as the red-bellied pacu (Piaractus brachypomus) and black pacu (Piaractus mesopotamicus), and Colossoma, represented by the giant pacu or tambaqui (Colossoma macropomum). Additional genera such as Mylossoma and Metynnis contribute smaller species commonly referred to as silver dollars or disk tetras.

Phylogenetic analyses have revealed that Pacu fish represent a monophyletic group that diverged from their carnivorous piranha ancestors approximately 25 million years ago during the Miocene epoch. This evolutionary split coincided with the development of specialized dental structures and digestive adaptations that enabled exploitation of plant-based food sources. The taxonomic distinction between Pacu fish and piranhas primarily rests on dental morphology, jaw structure, and feeding behavior rather than overall body plan, as both groups maintain similar compressed, deep-bodied forms.

Recent molecular studies have refined our understanding of serrasalmid relationships, revealing that some species traditionally classified as Pacu fish may require taxonomic revision. The genus Mylossoma, for instance, demonstrates intermediate characteristics between typical Pacu fish and their piranha relatives, suggesting a more complex evolutionary history than previously recognized.

Physical Description

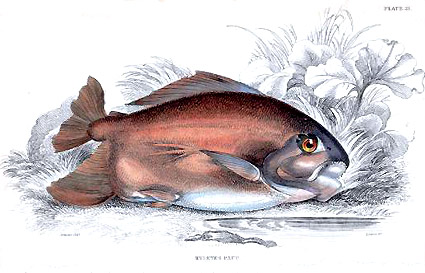

Pacu fish exhibit the characteristic deep, laterally compressed body plan typical of the Serrasalmidae family, though they generally achieve larger adult sizes than most piranha species. The largest species, Colossoma macropomum, can reach lengths exceeding 108 centimeters and weights approaching 40 kilograms, making them among the largest characin fish in South American waters. Most Pacu fish display silvery coloration with darker dorsal regions, though species-specific variations include the distinctive red or orange ventral coloration seen in Piaractus brachypomus and the uniform dark coloration of adult Piaractus mesopotamicus.

The most distinguishing feature separating Pacu fish from their piranha relatives lies in their dental structure. Rather than the sharp, triangular teeth adapted for flesh-shearing found in piranhas, Pacu fish possess broad, flattened molars arranged in multiple rows. These teeth, which bear remarkable resemblance to human molars, enable efficient crushing and grinding of hard plant materials including seeds, nuts, and woody plant tissues. The dental formula typically includes 2-3 rows of functional teeth in both upper and lower jaws, with replacement teeth continuously developing throughout the fish’s lifetime.

Pacu fish demonstrate sexual dimorphism that becomes pronounced during reproductive maturity. Males typically develop more elongated dorsal and anal fins, along with breeding tubercles on their gill covers and heads during spawning seasons. The adipose fin, characteristic of characin fish, remains prominent in all Pacu fish species and serves as a reliable taxonomic marker. Juvenile Pacu fish often display more pronounced spotting or banding patterns that fade as individuals mature, though species-specific variations in this pattern provide important identification characteristics.

Habitat & Distribution

Pacu fish demonstrate remarkable adaptability to diverse freshwater environments throughout their native Neotropical range. The Amazon River basin serves as the primary center of diversity, supporting populations across the extensive river networks of Brazil, Peru, Colombia, and surrounding nations. The Orinoco River system provides secondary habitat, particularly for Colossoma macropomum populations that utilize the seasonal flooding cycles characteristic of these watersheds. These species exhibit strong preferences for warm, slightly acidic waters with temperatures ranging from 24-30°C and pH values between 6.0-7.5.

Seasonal habitat utilization patterns reflect the complex hydrology of Amazonian river systems. During high-water periods, Pacu fish disperse into flooded forests where they access fallen fruits and seeds from riparian vegetation. These flooded areas, known locally as várzea, provide critical feeding and nursery habitat that supports juvenile recruitment and adult growth. As water levels recede, populations concentrate in main river channels and permanent water bodies where they may experience increased competition for limited food resources.

The biogeographic distribution of individual Pacu fish species demonstrates varying degrees of endemism and range restriction. While Colossoma macropomum maintains the broadest native distribution across the Amazon and Orinoco basins, species such as Piaractus mesopotamicus show more restricted ranges within specific drainage systems. Human introductions have dramatically expanded the global distribution of several Pacu fish species, with established populations now documented in Southeast Asia, Papua New Guinea, and various tropical regions where they support aquaculture fisheries.

Environmental factors influencing habitat selection include dissolved oxygen levels, water velocity, substrate composition, and food availability. Pacu fish generally prefer areas with moderate current flow and abundant riparian vegetation, though they demonstrate considerable tolerance for varying water quality conditions. This adaptability has contributed to their success as introduced species in non-native environments, though it also raises concerns about potential ecological impacts in recipient ecosystems.

Diet & Feeding Behavior

The feeding ecology of Pacu fish represents a remarkable evolutionary adaptation that distinguishes them from their carnivorous piranha relatives. These species function primarily as frugivores and seed dispersers, with their diet consisting largely of fallen fruits, seeds, nuts, and plant materials that enter aquatic systems from surrounding vegetation. During peak fruiting seasons, some Pacu fish species derive up to 80% of their nutritional intake from these plant-based sources, making them among the most herbivorous members of the characin family.

Seasonal dietary shifts reflect the natural flood pulse cycles of Neotropical river systems. During high-water periods when fruits and seeds are abundant, Pacu fish exhibit strong selectivity for high-energy plant materials including palm fruits, rubber tree seeds, and various leguminous pods. The powerful crushing action of their specialized molars enables processing of extremely hard materials, including seeds with tensile strengths exceeding 200 newtons per square centimeter. This capability allows access to nutritional resources unavailable to other fish species in the same habitat.

Opportunistic omnivory supplements the primarily plant-based diet, particularly during low-water periods when preferred plant materials become scarce. Pacu fish readily consume aquatic invertebrates, small crustaceans, and occasionally small fish, demonstrating remarkable dietary flexibility. Zooplankton and insect larvae provide important protein sources for juvenile individuals, while adults may consume larger invertebrates including freshwater crabs and snails. This dietary versatility contributes significantly to their success in both native and introduced environments.

Feeding behavior patterns show distinct temporal and spatial components. Many Pacu fish species exhibit crepuscular feeding activity, with peak foraging occurring during dawn and dusk periods when they move into shallow areas to access fallen plant materials. Group feeding behavior has been observed in several species, particularly during periods of abundant food availability, though territorial behavior may emerge when resources become limited.

Behavior & Adaptations

Pacu fish demonstrate complex behavioral adaptations that reflect their ecological role as primary consumers in Neotropical aquatic systems. Schooling behavior varies significantly among species and life stages, with juvenile individuals often forming large aggregations that provide protection from predators while facilitating efficient exploitation of dispersed food resources. Adult Pacu fish typically exhibit more solitary behavior, though loose aggregations may form during reproductive periods or when concentrated food sources are available.

Migratory behavior represents one of the most significant behavioral adaptations observed in Pacu fish populations. Many species undertake extensive spawning migrations that can cover hundreds of kilometers within river systems. These movements follow predictable seasonal patterns linked to flood pulse cycles, with upstream migrations typically occurring at the onset of high-water periods. The timing and extent of these migrations demonstrate remarkable precision, suggesting sophisticated environmental cuing mechanisms that respond to water temperature, photoperiod, and hydrological changes.

Habitat selection behavior reveals complex decision-making processes that balance feeding opportunities, predation risk, and physiological requirements. During daylight hours, many Pacu fish species seek shelter in deeper water or beneath overhanging vegetation, emerging during crepuscular periods to forage in shallow areas. This behavioral pattern reduces exposure to visual predators while maximizing access to food resources concentrated in littoral zones.

Social hierarchies and territorial behavior become particularly evident during reproductive periods. Dominant males establish and defend territories in shallow areas suitable for spawning, engaging in aggressive displays and physical confrontations with competing individuals. These behavioral adaptations ensure reproductive success while maintaining population structure necessary for effective seed dispersal and ecosystem function.

Reproduction & Life Cycle

The reproductive biology of Pacu fish reflects complex adaptations to the seasonal flood cycles characteristic of Neotropical river systems. Most species exhibit annual reproductive cycles triggered by environmental cues including water temperature, photoperiod, and rising water levels associated with rainy season onset. Sexual maturity varies significantly among species, with smaller species such as Mylossoma duriventre reaching maturity at 2-3 years, while larger species like Colossoma macropomum may require 4-6 years to achieve reproductive capability.

Spawning behavior demonstrates remarkable sophistication, with many species undertaking extensive migrations to reach optimal breeding habitat. These migrations often involve upstream movements of several hundred kilometers, with individuals demonstrating strong site fidelity to specific spawning areas used repeatedly across multiple reproductive seasons. The timing of these movements shows precise synchronization with environmental conditions, typically occurring during rising water periods when flooded areas provide abundant food resources for developing larvae.

Reproductive output correlates strongly with female body size, with larger individuals producing substantially more eggs than smaller counterparts. A mature female Colossoma macropomum may produce over one million eggs during a single spawning event, while smaller species typically produce 50,000-200,000 eggs. The eggs are pelagic and semi-adhesive, allowing dispersal by river currents while maintaining some attachment to vegetation or substrate materials.

Larval development follows patterns typical of characin fish, with newly hatched larvae possessing yolk sacs that sustain initial development. The transition to exogenous feeding occurs approximately 4-6 days post-hatching, when larvae begin consuming zooplankton and small organic particles. Juvenile growth rates vary considerably based on food availability and environmental conditions, with some species capable of reaching 20-30 centimeters in their first year under optimal conditions. This rapid growth provides advantages in avoiding predation while enabling exploitation of increasingly diverse food resources as individuals mature.

Predators & Threats

Pacu fish face predation pressure from various sources throughout their life cycle, with vulnerability patterns changing significantly as individuals mature. Juvenile Pacu fish experience heavy predation from numerous species including piranhas, catfish, cichlids, and various piscivorous birds. The large reproductive output typical of these species partially compensates for high juvenile mortality rates, though environmental factors significantly influence recruitment success.

Adult Pacu fish encounter fewer natural predators due to their substantial size, though several large predatory species pose significant threats. Caimans represent the primary vertebrate predators of adult Pacu fish, with both spectacled caimans and black caimans documented taking individuals up to moderate sizes. Large catfish species including pintado and dourado also prey upon Pacu fish, particularly during concentrated feeding periods when individuals may be more vulnerable to predation.

Anthropogenic threats have emerged as increasingly significant factors affecting Pacu fish populations throughout their native range. Overfishing represents the most immediate concern, with commercial and subsistence fisheries targeting these species for their high-quality protein and economic value. Dam construction and river modification projects disrupt critical migration routes and alter flood patterns necessary for successful reproduction. Deforestation in riparian zones reduces the availability of fruits and seeds that form the foundation of Pacu fish diets.

Water pollution from agricultural runoff, mining activities, and urban development creates additional stressors that may compromise immune function and reproductive success. Climate change effects including altered precipitation patterns and increased temperature extremes may disrupt the environmental cues that regulate reproductive timing and migration behavior. The introduction of non-native species in some areas creates competitive pressure and potential predation threats that native Pacu fish populations are not adapted to handle.

Conservation Status

The conservation status of Pacu fish species varies considerably across their taxonomic diversity, with most species currently classified as Least Concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). However, this classification may not accurately reflect population trends for several species experiencing significant anthropogenic pressures throughout their native ranges. Colossoma macropomum, despite its wide distribution and current stable status, has experienced documented population declines in several regions due to overfishing and habitat modification.

Population monitoring efforts remain inadequate for many Pacu fish species, particularly those with restricted distributions or those inhabiting remote areas of the Amazon basin. The lack of comprehensive population data creates challenges for accurate conservation assessment and may mask declining population trends in species currently classified as stable. Recent studies suggest that several Mylossoma species may warrant increased conservation attention due to habitat loss and fishing pressure.

Conservation efforts have focused primarily on sustainable fisheries management and habitat protection initiatives. Several South American countries have implemented seasonal fishing restrictions and minimum size limits designed to protect spawning populations during critical reproductive periods. The establishment of protected areas within key watershed systems provides habitat protection for multiple species while maintaining ecosystem connectivity necessary for migration and reproduction.

International cooperation has become increasingly important as Pacu fish populations span multiple national boundaries. The Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization coordinates regional conservation efforts, though implementation and enforcement remain challenging across the diverse political and economic landscape of the Amazon basin. Ex-situ conservation efforts including captive breeding programs have shown promise for maintaining genetic diversity and supporting population supplementation efforts where necessary.

Human Interaction

Human interactions with Pacu fish span thousands of years, with indigenous Amazonian peoples developing sophisticated knowledge of their behavior, ecology, and seasonal availability. Traditional fishing methods including hook-and-line techniques, fish traps, and seasonal harvesting practices reflect deep understanding of Pacu fish biology and sustainable resource utilization. These traditional practices often incorporated conservation measures such as seasonal restrictions and selective harvesting that maintained population stability.

Modern commercial fisheries represent the most significant contemporary human interaction with Pacu fish populations. These species support substantial commercial operations throughout South America, with annual harvest levels reaching thousands of tons in major river systems. The high-quality protein and favorable taste characteristics make Pacu fish highly valued in local and regional markets, creating economic incentives for continued exploitation.

Aquaculture development has transformed Pacu fish from wild-harvested resources to domesticated species supporting intensive production systems worldwide. Brazil leads global Pacu fish aquaculture production, with tambaqui (Colossoma macropomum) representing one of the most important freshwater species in South American aquaculture. These operations have developed specialized breeding programs, nutritional protocols, and production systems optimized for commercial efficiency.

Recreational fishing for Pacu fish has gained popularity among sport fishing enthusiasts attracted to their substantial size and fighting ability. Specialized river fishing techniques have evolved to target these species effectively, with many anglers traveling considerable distances to access prime Pacu fish habitat. The development of catch-and-release practices among recreational fishers contributes to conservation efforts while maintaining economic benefits for local communities.

Introduction of Pacu fish species outside their native range has created both opportunities and challenges for human interactions. While these introductions support aquaculture development in tropical regions, they also raise concerns about ecological impacts and require careful management to prevent negative environmental consequences.

Interesting Facts

Pacu fish possess remarkable dental adaptations that have earned them the nickname “vegetarian piranhas” due to their distinctly human-like molars. These teeth continuously grow throughout their lifetime, requiring constant wear from processing hard plant materials to maintain proper length and function. The similarity to human dental structure is so pronounced that archaeological specimens have occasionally been misidentified as human remains.

The seed dispersal services provided by Pacu fish prove essential for maintaining rainforest diversity throughout Amazonian ecosystems. Studies have documented over 200 plant species whose seeds pass through Pacu fish digestive systems, with many showing enhanced germination rates following gut passage. This mutualistic relationship has persisted for millions of years and represents one of the most important ecological functions performed by these species.

Pacu fish demonstrate remarkable physiological adaptations that enable survival in oxygen-poor environments typical of Amazonian floodplains. During periods of low dissolved oxygen, these species can extract oxygen from air using specialized modifications of their swim bladder, effectively functioning as a primitive lung. This adaptation allows them to survive in environments that would be lethal to most other fish species.

The largest recorded Pacu fish, a Colossoma macropomum specimen caught in the Amazon River, measured 1.12 meters in length and weighed 42.5 kilograms, making it one of the largest characin fish ever documented. This exceptional size demonstrates the growth potential possible under optimal environmental conditions and abundant food resources.

Cultural significance extends beyond subsistence use, with many Amazonian indigenous groups incorporating Pacu fish into traditional ceremonies and seasonal celebrations. The timing of spawning migrations serves as a natural calendar system that helps coordinate community activities and agricultural practices with environmental cycles.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Pacu fish dangerous to humans?

Pacu fish pose minimal threat to humans, despite occasional sensationalized media reports. Their dental structure is adapted for crushing plant materials rather than flesh, and documented cases of human injury are extremely rare. Most reported incidents involve accidental contact during handling or fishing activities rather than aggressive behavior toward humans.

Can Pacu fish survive in North American waters?

While Pacu fish demonstrate considerable environmental tolerance, most species cannot survive cold temperatures typical of temperate North American winters. Individuals occasionally discovered in northern waters typically represent aquarium releases that survive temporarily during warm seasons but cannot establish permanent populations due to thermal limitations.

What is the difference between Pacu fish and piranhas?

The primary differences lie in dental structure and feeding behavior. Pacu fish possess flat, crushing teeth adapted for plant materials, while piranhas have sharp, pointed teeth designed for cutting flesh. Additionally, Pacu fish typically achieve larger adult sizes and demonstrate primarily herbivorous feeding habits compared to the carnivorous nature of most piranha species.

How fast do Pacu fish grow in aquaculture systems?

Growth rates vary significantly among species and environmental conditions, but most commercially cultured Pacu fish can reach marketable size within 12-18 months under optimal aquaculture conditions. Colossoma macropomum demonstrates particularly rapid growth, potentially reaching 2-3 kilograms within two years when provided with proper nutrition and environmental conditions.

Conclusion

Pacu fish represent remarkable examples of evolutionary adaptation and ecological specialization within Neotropical freshwater systems. Their dual role as both economically important species supporting substantial fisheries and aquaculture operations, and ecologically critical seed dispersers maintaining rainforest diversity, underscores their significance beyond simple commercial value. Continued research and conservation efforts remain essential for ensuring these species continue to fulfill their vital ecological functions while supporting sustainable human utilization throughout their native and introduced ranges.

Share The Article:

More Fish Species:

-

Tiger Barb

The Tiger Barb (Puntigrus tetrazona) stands as one of Southeast Asia’s most recognizable freshwater cyprinids, distinguished by its vibrant…

-

Kissing Gourami

The Kissing Gourami (*Helostoma temminckii*) stands as one of the most distinctive and recognizable freshwater fish species in both…

-

Head and Tail Light Tetra

The Head and Tail Light Tetra (*Hemigrammus ocellifer*) stands as one of South America’s most distinctive characin species, instantly…

-

Pelagic Thresher Shark

The Pelagic Thresher Shark stands as one of the ocean’s most distinctive and efficient predators, renowned for its dramatically…

-

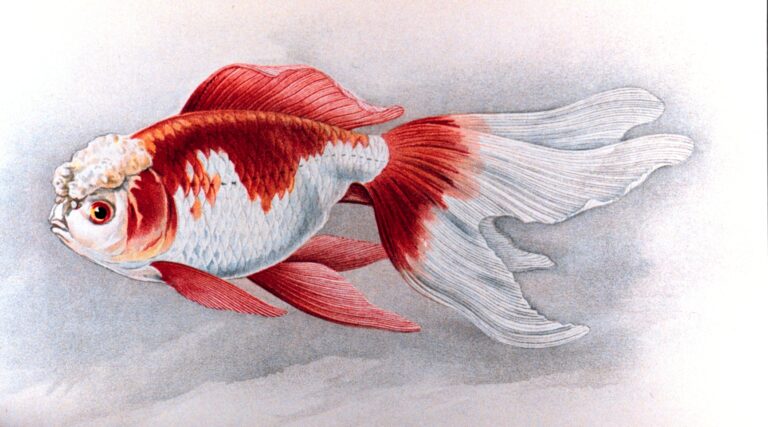

Oranda Goldfish

The Oranda Goldfish (Carassius auratus) stands as one of the most distinctive and cherished varieties in the world of…

-

Convict Cichlid

The Convict Cichlid (Amatitlania nigrofasciata) stands as one of the most recognizable and widely distributed freshwater fish species in…

Discover

-

History of Fly Fishing: Ancient Origins to Modern Mastery

The gentle art of fly fishing has captivated anglers for centuries, evolving from a practical method of obtaining food…

-

Deep Water Fishing Mastery: 7 Proven Strategies

When surface waters turn quiet and shoreline spots fail to produce, the answer often lies in the depths. Deep…

-

Fly Fishing | How to fly fish in 2025?

Fly fishing has changed a lot since I first picked up a rod back in the mid-90s. The fundamentals…

-

How I Caught a 47-Pound Goliath: Big Grouper Fishing Guide

That morning started like most fishing trips – with complete optimism followed by immediate disappointment. We’d motored 12 miles…

-

Louisiana Redfish Fishing: Best Spots & Tactics for Beginners

Finding that first bull red is a moment you never forget. The pull, the power – it’s something special….

-

Night Fishing for Beginners: Expert Techniques That Actually Work

My first night fishing trip was an absolute disaster. Picture this – fifteen-year-old me, armed with a rusty flashlight…

Discover

-

Green Terror Cichlid

The Green Terror Cichlid stands as one of South America’s most formidable and visually striking freshwater fish species, commanding…

-

Crown Tail Betta

The Crown Tail Betta stands as one of aquaculture’s most distinctive ornamental fish, renowned for its dramatically elongated, spiky…

-

White Catfish

The White Catfish represents one of North America’s most adaptable freshwater species, serving as both an important commercial fish…

-

Alaska Salmon Fishing: Planning Your Trip to the Last Frontier

I still remember the first time I hooked into a Kenai River king salmon. It was July 15, 2019,…

-

River Fishing Techniques: Master the Moving Water

Fishing rivers presents a unique set of challenges and rewards that I’ve come to appreciate over my three decades…

-

Marble Molly

The Marble Molly (*Poecilia latipinna*) stands as one of the most recognizable and widely distributed ornamental fish species in…