Head and Tail Light Tetra

By Ryan Maron | Last Modified: June 8, 2025

The Head and Tail Light Tetra (*Hemigrammus ocellifer*) stands as one of South America’s most distinctive characin species, instantly recognizable by the luminous spots that adorn its head and caudal peduncle. This small freshwater fish has captured the attention of aquarists worldwide while maintaining significant ecological importance within the Amazon Basin’s complex river systems. Native to the slow-moving waters of Brazil, Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana, the Head and Tail Light Tetra serves as both a crucial prey species for larger predators and an effective controller of small invertebrate populations.

As a schooling species, the Head and Tail Light Tetra demonstrates remarkable social cohesion that contributes to the stability of neotropical freshwater ecosystems. Their feeding behavior helps regulate populations of microscopic organisms, while their position in the food web supports diverse predator communities including larger fish, birds, and aquatic reptiles. The species’ adaptability to varying water conditions and their prolific breeding patterns have established them as both ecologically significant and commercially valuable in the aquarium trade.

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Common Name | Head and Tail Light Tetra |

| Scientific Name | Hemigrammus ocellifer |

| Family | Characidae |

| Typical Size | 4-5 cm (1.6-2.0 inches), 2-3 grams |

| Habitat | Slow-moving rivers and tributaries |

| Diet | Omnivorous micro-predator |

| Distribution | Amazon Basin, Guianas |

| Conservation Status | Least Concern |

Taxonomy & Classification

The Head and Tail Light Tetra belongs to the extensive family Characidae, which encompasses over 1,100 species of freshwater fish distributed throughout South and Central America, Africa, and southern North America. Within this diverse family, *Hemigrammus ocellifer* represents one of approximately 50 species in the genus *Hemigrammus*, a group characterized by their small size, schooling behavior, and distinctive color patterns.

Swedish ichthyologist Carl H. Eigenmann first described the species in 1909, establishing its taxonomic position based on specimens collected from British Guiana. The specific epithet “ocellifer” derives from Latin, meaning “bearing eye-spots,” directly referencing the characteristic luminous spots that distinguish this species from its congeners. Recent molecular phylogenetic studies have confirmed the Head and Tail Light Tetra’s placement within the subfamily Characinae, alongside other small tetras that share similar ecological niches and morphological features.

The genus *Hemigrammus* forms part of a larger clade that includes closely related genera such as *Hyphessobrycon* and *Moenkhausia*. These relationships reflect evolutionary adaptations to similar environmental pressures within South American river systems, resulting in convergent morphological and behavioral traits among species that occupy comparable ecological roles.

Physical Description

The Head and Tail Light Tetra exhibits a streamlined, laterally compressed body typical of active swimming characins. Adult specimens reach maximum lengths of 5 centimeters, with females generally displaying slightly more robust bodies than males. The species’ most distinctive feature consists of two prominent, iridescent spots: one positioned behind the operculum near the head, and another at the base of the caudal fin. These spots appear bright copper or gold under proper lighting conditions, creating the “light” effect that inspired the common name.

The overall body coloration presents a translucent silver-white base with subtle iridescent qualities that shift between blue and green depending on lighting angles. A faint dark stripe extends horizontally along the midline from behind the operculum to the caudal peduncle, becoming more pronounced during periods of stress or excitement. The dorsal fin displays a distinct black marking along its anterior edge, while the anal fin often shows reddish or orange tinting, particularly in mature specimens.

Sexual dimorphism becomes apparent in adult Head and Tail Light Tetras, with males developing more intense coloration and slightly longer dorsal fin rays during breeding condition. Females maintain a more subdued appearance but develop noticeably fuller abdomens when gravid with eggs. The species possesses the typical characiform adipose fin, a small, fleshy appendage located between the dorsal and caudal fins that serves as a taxonomic identifier for the order Characiformes.

Habitat & Distribution

The Head and Tail Light Tetra inhabits the vast network of rivers and tributaries throughout the northern Amazon Basin, with confirmed populations in Brazil, Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana. Their distribution centers on slow-moving waters with moderate current flow, including both blackwater and clearwater systems where dissolved organic compounds create slightly acidic conditions ranging from pH 5.5 to 7.0.

These fish demonstrate remarkable adaptability to various aquatic environments within their range, from small forest streams barely a meter wide to major river tributaries spanning several kilometers. Water temperatures in their natural habitat fluctuate between 24-28°C (75-82°F) throughout the year, with seasonal variations corresponding to wet and dry periods. During the rainy season, rising water levels provide access to flooded forest areas where abundant food sources support large congregations of schooling tetras.

The species shows particular affinity for areas with overhanging vegetation and submerged woody debris, which provide both shelter from predators and hunting grounds for small invertebrates. Conductivity levels in their natural waters typically range from 10-150 microsiemens per centimeter, reflecting the low mineral content characteristic of many Amazonian waterways. Similar to other tetra fish varieties, they prefer areas with gentle water movement that allows for energy-efficient swimming while maintaining access to drift organisms.

Diet & Feeding Behavior

The Head and Tail Light Tetra functions as an opportunistic omnivore, displaying feeding behaviors that adapt to seasonal availability of food sources throughout their natural range. Their primary diet consists of small invertebrates including mosquito larvae, chironomid midges, small crustaceans, and various zooplankton species. During periods of high water, when terrestrial insects fall into the river systems, these tetras readily consume ants, small flies, and other arthropods that supplement their aquatic prey base.

Plant matter comprises a significant portion of their nutritional intake, particularly during dry seasons when animal protein becomes less abundant. They consume algae, small seeds, and decomposing organic matter, utilizing specialized pharyngeal teeth to process plant materials effectively. Their feeding strategy involves continuous grazing throughout daylight hours, with peak activity occurring during early morning and late afternoon periods when prey density reaches optimal levels.

The schooling behavior of Head and Tail Light Tetras enhances their feeding efficiency through cooperative foraging strategies. Groups of 20-50 individuals systematically work through areas of high food concentration, with lead fish alerting others to productive feeding zones through subtle behavioral cues. This collective approach allows them to exploit patchy food distributions more effectively than solitary feeding would permit, while simultaneously maintaining vigilance against potential predators during vulnerable feeding periods.

Behavior & Adaptations

Head and Tail Light Tetras exhibit complex schooling behaviors that serve multiple ecological functions beyond simple predator avoidance. Their shoals demonstrate sophisticated coordination patterns, with individuals maintaining precise spacing and synchronized swimming movements that reduce energy expenditure through hydrodynamic benefits. The characteristic light spots play crucial roles in intraspecific communication, particularly during low-light conditions when visual contact between school members becomes challenging.

The species displays distinct diurnal activity patterns, becoming most active during dawn and dusk periods when their prey organisms show increased movement. During midday hours, schools often seek shelter among submerged vegetation or overhanging banks, adopting a more sedentary behavior pattern that conserves energy and reduces predation risk. These behavioral adaptations align with the feeding schedules of larger predatory fish that hunt primarily during bright daylight conditions.

Territorial behavior emerges during breeding seasons when mature individuals establish temporary territories around suitable spawning sites. Males develop heightened aggression toward other males while displaying elaborate courtship behaviors involving rapid swimming patterns and enhanced coloration. The species demonstrates remarkable adaptability to environmental changes, adjusting school size and behavior patterns in response to seasonal water level fluctuations, temperature variations, and predator density changes.

Reproduction & Life Cycle

The reproductive cycle of Head and Tail Light Tetras closely follows seasonal patterns associated with Amazonian wet and dry periods. Spawning typically occurs during the early rainy season when rising water levels provide access to flooded vegetation areas that offer ideal nursery conditions. Water temperature increases and improved food availability trigger hormonal changes that initiate reproductive behavior in mature individuals.

Courtship begins with males establishing temporary territories in areas with fine-leaved aquatic plants or submerged root systems. Males display intensified coloration and perform elaborate swimming displays to attract gravid females, often involving rapid circular movements and fin displays that showcase their breeding condition. Successful pairs engage in spawning behavior during early morning hours, with females releasing 200-300 adhesive eggs that males fertilize immediately.

The spawning process involves synchronized swimming movements where pairs ascend rapidly through the water column before releasing gametes simultaneously. Eggs adhere to vegetation or fall into crevices among roots and debris, where they remain relatively protected from predation. Incubation requires 24-36 hours at temperatures between 26-28°C, with newly hatched larvae remaining attached to vegetation for an additional 3-4 days while absorbing their yolk sacs.

Larval development proceeds rapidly, with free-swimming fry beginning to feed on microscopic organisms within one week of hatching. Growth rates depend heavily on food availability and water temperature, with juveniles reaching sexual maturity at approximately 8-10 months under optimal conditions. The species can potentially live 3-5 years in natural conditions, though predation pressure typically limits average lifespans to 2-3 years.

Predators & Threats

Head and Tail Light Tetras face predation pressure from diverse groups of aquatic and semi-aquatic predators throughout their range. Larger characin species, including piranhas and other predatory tetras, represent primary fish predators that actively hunt schools of small tetras. Cichlid species such as peacock bass (*Cichla* spp.) and various pike cichlids pose significant threats, particularly to juvenile tetras that lack the speed and coordination of adult schools.

Avian predators play substantial roles in tetra mortality, with kingfishers, herons, and other fish-eating birds targeting schools in shallow water areas. The species’ schooling behavior provides some protection through confusion effects and diluted predation risk, but also makes them more conspicuous to visual predators when feeding in open water. Aquatic reptiles, including caimans and various snake species, opportunistically consume tetras when encountering schools during their own foraging activities.

Human activities present increasing challenges to Head and Tail Light Tetra populations across their range. Deforestation along riverbanks eliminates critical overhanging vegetation that provides shelter and food sources. Agricultural runoff introduces pesticides and fertilizers that disrupt aquatic food webs and directly impact tetra health. Mining operations, particularly gold mining, release mercury and other heavy metals that bioaccumulate in small fish species like tetras.

Climate change effects, including altered precipitation patterns and temperature fluctuations, threaten the seasonal flooding cycles that trigger reproduction and provide access to critical nursery habitats. Despite these pressures, the species’ wide distribution and adaptability have maintained stable population levels throughout most of their range.

Conservation Status

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) currently classifies the Head and Tail Light Tetra as “Least Concern” based on their extensive distribution range and stable population trends. This designation reflects the species’ adaptability to various aquatic environments and their continued abundance throughout the northern Amazon Basin. However, localized population declines have been documented in areas experiencing intensive human development or environmental degradation.

Regional conservation efforts focus primarily on habitat preservation rather than species-specific protections. The establishment of protected areas along major tributaries provides indirect benefits to Head and Tail Light Tetra populations by maintaining critical spawning and nursery habitats. Brazil’s environmental agencies monitor water quality parameters in key river systems, tracking changes that could impact small characin species collectively.

The commercial aquarium trade has created both opportunities and challenges for conservation. Sustainable collection practices in some areas provide economic incentives for local communities to maintain healthy river ecosystems. However, overcollection in accessible locations has led to temporary population reductions, prompting recommendations for collection quotas and seasonal restrictions during breeding periods.

Research initiatives supported by international conservation organizations continue monitoring Head and Tail Light Tetra populations as indicator species for broader ecosystem health. Their sensitivity to water quality changes makes them valuable early warning indicators for environmental degradation that could affect entire aquatic communities. Continued habitat protection and sustainable use practices will likely maintain their favorable conservation status for the foreseeable future.

Human Interaction

The Head and Tail Light Tetra has maintained a prominent position in the international aquarium trade since the mid-20th century, when improved transportation methods made South American fish species widely available to hobbyists. Their peaceful temperament, attractive appearance, and relatively simple care requirements have established them as popular choices for community aquarium setups. Annual export numbers from South American countries reach several hundred thousand specimens, generating significant revenue for local collection operations and supporting rural economies.

In their native range, indigenous communities have traditionally included Head and Tail Light Tetras in subsistence fishing activities, though their small size limits their importance as primary food sources. Modern indigenous fishing practices often incorporate tetras as bait for larger species, taking advantage of their abundance and attractiveness to predatory fish. Some communities have developed specialized techniques for capturing small schooling fish using traditional nets and traps.

Scientific research involving Head and Tail Light Tetras has contributed valuable insights into tropical freshwater ecology, schooling behavior, and conservation biology. Their use as model organisms in laboratory studies has advanced understanding of fish behavior, reproductive biology, and responses to environmental stressors. University research programs throughout South America utilize these tetras for student training in ichthyology and aquatic ecology.

The species serves important ecological functions that indirectly benefit human communities dependent on healthy river ecosystems. Their role in controlling mosquito larvae populations provides natural pest management services, while their position in food webs supports commercially important fish species that rely on healthy prey populations.

Interesting Facts

The luminous spots that give the Head and Tail Light Tetra its distinctive name contain specialized cells called iridophores that reflect light through stacks of crystalline platelets. These structures can be adjusted to control the intensity and angle of light reflection, allowing fish to communicate with school members and potentially confuse predators through rapid flashing movements.

Head and Tail Light Tetras demonstrate remarkable navigation abilities during seasonal migrations between main river channels and flooded forest areas. Research has shown they can navigate using combinations of chemical cues, water current patterns, and celestial navigation, returning to the same spawning areas year after year with extraordinary precision.

The species exhibits interesting size-dependent schooling behaviors, with larger individuals typically assuming leadership positions at the front of moving schools. These lead fish make crucial decisions about feeding locations, predator avoidance maneuvers, and migration routes, with followers responding to subtle visual and hydrodynamic cues within milliseconds.

During the peak of the rainy season, massive aggregations of Head and Tail Light Tetras can contain thousands of individuals spanning several hectares of flooded forest. These super-schools create spectacular underwater displays that have attracted scientific expeditions and underwater photographers from around the world.

The species possesses unusually sensitive lateral line systems that detect minute water movements from distances exceeding their body length. This adaptation allows them to coordinate school movements with remarkable precision and detect approaching predators before visual contact occurs.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long do Head and Tail Light Tetras live in aquarium conditions?

In well-maintained aquarium environments, Head and Tail Light Tetras typically live 4-6 years, which exceeds their natural lifespan due to reduced predation pressure and consistent food availability. Optimal water conditions, proper nutrition, and appropriate tank mates contribute significantly to their longevity in captivity.

What water parameters do Head and Tail Light Tetras require for optimal health?

These tetras thrive in water temperatures between 24-28°C (75-82°F) with pH levels ranging from 6.0-7.5 and soft to moderately hard water conditions. They prefer well-oxygenated water with gentle current flow and benefit from regular water changes to maintain water quality. Like other tropical aquarium species, they require stable water parameters to prevent stress-related health issues.

How many Head and Tail Light Tetras should be kept together in an aquarium?

These fish should be maintained in groups of at least 6-8 individuals to exhibit natural schooling behaviors and reduce stress levels. Larger groups of 10-15 tetras create more impressive displays and allow for more complex social interactions that benefit their overall health and behavior patterns.

Can Head and Tail Light Tetras be bred successfully in home aquariums?

Breeding Head and Tail Light Tetras in aquarium settings requires specific conditions including slightly warmer water temperatures, fine-leaved plants for egg deposition, and separate breeding tanks to protect eggs and fry from adult fish. Success rates improve significantly when pairs are conditioned with high-quality foods and provided with appropriate spawning substrates.

Conclusion

The Head and Tail Light Tetra exemplifies the remarkable diversity and ecological importance of South American characin species within neotropical freshwater ecosystems. Their dual role as both predator and prey species, combined with their efficient resource utilization and adaptive schooling behaviors, demonstrates the complex interconnections that maintain stability in Amazon Basin aquatic communities. Continued conservation of their natural habitats remains essential for preserving these intricate ecological relationships and supporting the biodiversity that makes South American river systems among the world’s most productive freshwater environments.

Share The Article:

More Fish Species:

-

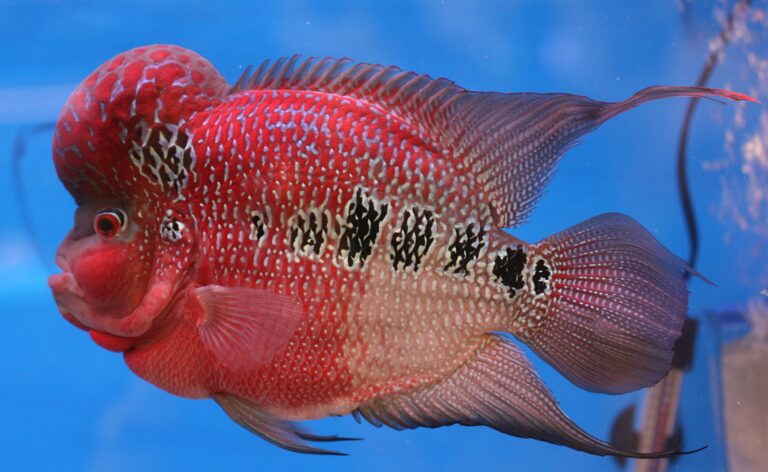

Flowerhorn Cichlid

The Flowerhorn Cichlid represents one of the most distinctive and culturally significant hybrid fish species in contemporary aquarium keeping….

-

Mosquito Fish

The Mosquito Fish (Gambusia affinis) stands as one of North America’s most ecologically significant freshwater species, despite its diminutive…

-

Double Tail Betta

The Double Tail Betta, scientifically known as Betta splendens, represents one of the most distinctive and captivating variants within…

-

Yellow Lab Cichlid

The Yellow Lab Cichlid (*Labidochromis caeruleus*) stands as one of Africa’s most recognizable freshwater fish species, distinguished by its…

-

Bigeye Thresher Shark

The Bigeye Thresher Shark represents one of the ocean’s most extraordinary predators, distinguished by its dramatically elongated tail fin…

-

Corydoras Catfish

Corydoras catfish represent one of the most diverse and ecologically significant groups of freshwater bottom-dwelling fish in South American…

Discover

-

Whale Shark

The whale shark (*Rhincodon typus*) stands as the ocean’s largest fish species, representing one of nature’s most remarkable gentle…

-

How to Fish with Dry Flies: Beginner’s Guide to Surface Action

There’s something almost magical about watching a trout rise to sip your dry fly from the surface. I still…

-

Monster Muskie Fishing: Top Lures and Locations for Trophy Fish

There’s nothing – and I mean absolutely nothing – that compares to the heart-stopping moment when a monster muskie…

-

How to Become a Better Fisherman in 2025: Master These 5 Skills

There’s something magical about that moment when your line goes tight and you feel the unmistakable pull of a…

-

7 Best Family-Friendly Fishing Destinations in the U.S. (Tested with Kids!)

I still remember the first time I took my son Tommy fishing. He was five, armed with a Spider-Man…

-

Basic Fishing Techniques: Master the Fundamentals

There’s something magical about that first tug on your fishing line. I still remember mine, a scrappy bluegill on…

Discover

-

Bass Fishing Techniques: Expert Tips That Actually Work

Bass fishing has been my passion for over three decades, and if there’s one thing I’ve learned, it’s that…

-

Banana Fishing Myths Busted: The Truth Behind Fishing’s Strangest Superstition

Ask any hardcore angler about bringing a banana on their boat, and you might get a reaction stronger than…

-

How to Fish for Salmon in 2025: Expert Tips and Techniques

Few fishing experiences match the thrill of feeling a salmon take your line. These powerful fish have captivated anglers…

-

Guppy

The Guppy (Poecilia reticulata) stands as one of the most recognizable and extensively studied freshwater fish species in the…

-

Surfcasting Techniques: Master Beach Fishing and Catch More Fish

There’s something almost magical about standing at the edge of an ocean, rod in hand, as waves crash around…

-

Fishing Ethics: Conservation, Catch-and-Release, and Angler Responsibility

I was ten years old when my grandfather caught me throwing rocks at a school of bluegill near our…