Goldfish

By Ryan Maron | Last Modified: June 4, 2025

The goldfish (Carassius auratus) stands as one of the most culturally significant and scientifically fascinating species in freshwater aquaculture and ecology. Originally native to East Asia, this hardy cyprinid has become the world’s most popular ornamental fish while simultaneously establishing itself as a formidable invasive species across multiple continents. The goldfish represents a remarkable case study in selective breeding, ecological adaptation, and human-mediated species dispersal that has fundamentally altered aquatic ecosystems worldwide.

Beyond its ornamental value, the goldfish plays critical ecological roles as both predator and prey in aquatic food webs. In their native range, these fish serve as important mid-level consumers, controlling invertebrate populations while providing sustenance for larger piscivorous species. However, in non-native environments, goldfish often disrupt established ecological balances through their opportunistic feeding behavior and rapid reproduction rates, making them a species of significant conservation concern.

| Feature | Details |

| Common Name | Goldfish |

| Scientific Name | Carassius auratus |

| Family | Cyprinidae |

| Typical Size | 15-45 cm (6-18 inches), 50-3000g |

| Habitat | Freshwater lakes, ponds, slow rivers |

| Diet | Omnivorous – plants, invertebrates, detritus |

| Distribution | Worldwide (native to East Asia) |

| Conservation Status | Least Concern (Vulnerable in native range) |

Taxonomy & Classification

The goldfish belongs to the family Cyprinidae, the largest family of freshwater fish comprising over 3,000 species worldwide. Within this diverse group, Carassius auratus shares its genus with the crucian carp (C. carassius) and Prussian carp (C. gibelio), forming a closely related complex that has challenged taxonomists for decades. Recent phylogenetic analyses using mitochondrial DNA markers have confirmed that goldfish represent a distinct evolutionary lineage that diverged from its sister species approximately 12-15 million years ago.

The species exhibits remarkable genetic plasticity, with wild populations showing significant chromosomal variation ranging from diploid (2n=100) to hexaploid (6n=300) forms. This polyploid nature contributes to the goldfish’s exceptional adaptability and has facilitated the development of numerous ornamental varieties through selective breeding. Taxonomic classification places goldfish within the subfamily Cyprininae, alongside other Asian carps that share similar ecological niches and morphological characteristics.

Molecular studies have revealed that domesticated goldfish populations maintain surprisingly high genetic diversity despite centuries of selective breeding. This genetic resilience has enabled feral populations to establish successfully across diverse environmental conditions, often hybridizing with native cyprinid species and creating complex evolutionary dynamics in invaded ecosystems.

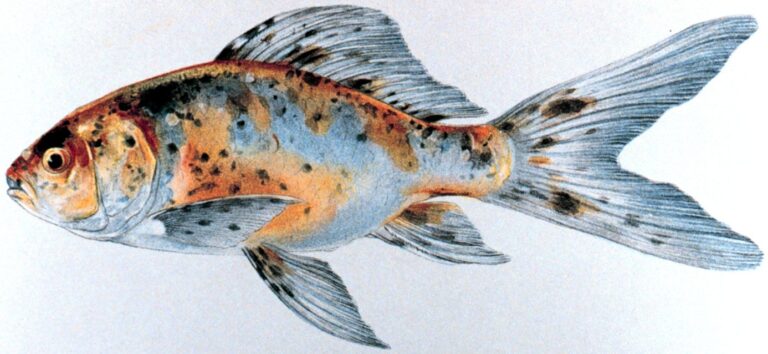

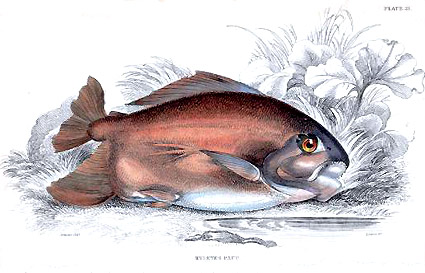

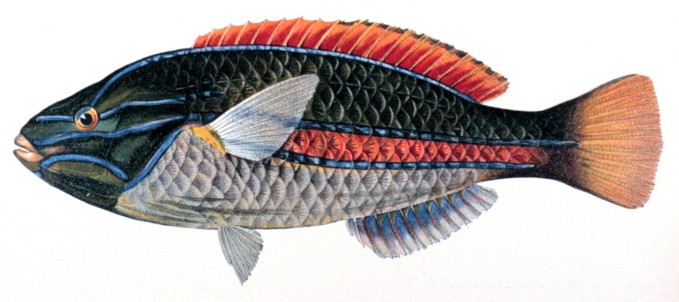

Physical Description

Wild goldfish typically exhibit a robust, laterally compressed body form optimized for life in slow-moving or static freshwater environments. Adult specimens commonly reach lengths of 15-30 centimeters, though individuals in optimal conditions can exceed 45 centimeters and weigh over 3 kilograms. The species displays pronounced sexual dimorphism, with females generally achieving larger sizes and more rounded body profiles compared to males, particularly during spawning season.

Coloration in wild populations ranges from olive-bronze to gold-yellow, providing effective camouflage against muddy substrates and aquatic vegetation. The distinctive golden coloration results from selective expression of chromatophores containing yellow and red pigments, while the absence of dark melanophores creates the bright appearance prized in ornamental varieties. This color variation represents one of the earliest documented examples of artificial selection in aquaculture.

Goldfish possess a complete lateral line system extending along both flanks, containing approximately 27-32 scales that house neuromast organs for detecting water movement and pressure changes. Their pharyngeal teeth arrangement (1,1,3-3,1,1) reflects their omnivorous feeding strategy, with grinding surfaces adapted for processing both plant matter and small invertebrates. The absence of barbels distinguishes goldfish from many related cyprinid species and reflects their adaptation to filter-feeding and surface-oriented foraging behaviors.

Habitat & Distribution

Originally endemic to the freshwater systems of eastern China, Mongolia, and Siberia, goldfish have achieved one of the most extensive global distributions of any freshwater fish species. Their native range encompasses the Amur River basin, Yellow River, and Yangtze River systems, where they inhabit shallow lakes, ponds, and slow-flowing tributaries characterized by abundant vegetation and soft substrates.

Contemporary goldfish populations thrive across six continents, establishing reproducing populations in temperate and subtropical regions worldwide. Successful invasions have been documented across North America, Europe, Australia, and parts of South America, where introduced populations often outcompete native species for resources. These feral populations demonstrate remarkable habitat flexibility, colonizing environments ranging from urban park ponds to large natural lake systems.

Optimal goldfish habitat features water temperatures between 15-25°C, dissolved oxygen levels above 5 mg/L, and pH ranges from 6.5-8.5. The species exhibits exceptional tolerance to environmental extremes, surviving temporary freezing conditions and oxygen depletion that would prove fatal to most temperate freshwater fish. This physiological resilience, combined with their generalist feeding habits, enables goldfish to establish viable populations in degraded or marginal aquatic environments where native species struggle to persist.

Diet & Feeding Behavior

Goldfish exhibit highly opportunistic omnivorous feeding behavior that adapts readily to seasonal resource availability and habitat conditions. Their diet encompasses a diverse array of food sources including aquatic invertebrates, zooplankton, plant matter, algae, and organic detritus. This dietary flexibility represents a key factor in their success as both ornamental fish and invasive species across varied ecological contexts.

Foraging behavior varies significantly with environmental conditions and prey density. In shallow, vegetated areas, goldfish employ a characteristic head-down feeding posture to extract benthic invertebrates from sediments, often creating visible disturbance plumes that can increase water turbidity. During peak invertebrate abundance, they demonstrate selective predation on chironomid larvae, oligochaete worms, and small crustaceans that provide essential protein for growth and reproduction.

Seasonal dietary shifts reflect changing resource availability and metabolic demands. Spring and summer feeding focuses heavily on protein-rich invertebrates to support reproductive development and rapid growth. As water temperatures decline in autumn, goldfish increase consumption of plant materials and stored carbohydrates, building energy reserves necessary for overwintering survival. This behavioral plasticity enables populations to persist in environments with fluctuating food resources and varying seasonal productivity cycles.

Behavior & Adaptations

Goldfish display complex social behaviors that vary significantly between wild and captive populations. In natural environments, they form loose aggregations that provide protection from predators while facilitating efficient resource exploitation. These schooling behaviors become most pronounced during spawning periods and when foraging in open water areas where predation risk remains elevated.

Temperature adaptation represents one of the species’ most remarkable physiological capabilities. Goldfish can survive prolonged exposure to near-freezing temperatures through behavioral and metabolic adjustments including reduced activity levels, decreased feeding rates, and enhanced glucose metabolism. During extreme cold periods, they enter a state of reduced metabolic activity similar to hibernation, allowing survival in ice-covered water bodies that would eliminate less adapted species.

Cognitive studies have revealed surprising learning capabilities in goldfish, including spatial memory formation, classical conditioning responses, and social learning behaviors. These intellectual adaptations enhance foraging efficiency and predator avoidance, contributing to their success in novel environments. Recent research has documented goldfish demonstrating time-place learning, remembering feeding locations and timing with remarkable precision over extended periods.

Reproduction & Life Cycle

Goldfish reproduction follows a seasonal pattern synchronized with water temperature increases and photoperiod changes typical of temperate freshwater fish. Spawning typically occurs when water temperatures reach 16-24°C, generally during late spring and early summer months in temperate regions. Sexual maturity is achieved at 1-2 years of age, depending on environmental conditions and nutritional status.

Reproductive behavior involves elaborate courtship displays where males develop prominent breeding tubercles on their gill covers and pectoral fins. Males actively pursue females through shallow, vegetated areas, engaging in characteristic chasing and nudging behaviors that stimulate egg release. Females produce 2,000-4,000 adhesive eggs per spawning event, though large individuals may release up to 10,000 eggs during peak reproductive condition.

Embryonic development proceeds rapidly at optimal temperatures, with hatching occurring 4-7 days post-fertilization. Larval goldfish initially rely on yolk reserves before transitioning to external feeding on microscopic zooplankton and algae. Growth rates vary considerably with temperature and food availability, but juvenile fish commonly reach 5-8 centimeters by their first winter. This rapid development cycle enables populations to establish quickly in suitable habitats and recover from environmental disturbances.

Predators & Threats

Adult goldfish face predation from a diverse array of piscivorous species including northern pike, largemouth bass, walleye, and various bird species such as herons, cormorants, and kingfishers. Juvenile goldfish are particularly vulnerable to predation from smaller fish species, aquatic insects, and amphibians during their first year of life. However, their schooling behavior and habitat selection often provide effective protection against many potential predators.

Disease represents a significant threat to both wild and captive goldfish populations. Common pathogens include bacterial infections (Aeromonas, Pseudomonas), parasitic diseases (Ichthyophthirius, Gyrodactylus), and viral conditions that can cause mass mortality events. Environmental stressors such as poor water quality, temperature fluctuations, and overcrowding significantly increase disease susceptibility and transmission rates.

Habitat degradation poses the most serious long-term threat to goldfish populations, particularly in their native range where pollution, dam construction, and water diversions have severely impacted natural spawning areas. Ironically, while goldfish thrive as invasive species globally, wild populations in their ancestral habitats face increasing pressure from human development and environmental modification. Climate change may further stress native populations through altered precipitation patterns and extreme temperature events.

Conservation Status

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classifies goldfish as Least Concern globally, reflecting their widespread distribution and stable populations across introduced ranges. However, this classification masks significant regional variations in population status, particularly within the species’ native range where wild populations face increasing environmental pressures and habitat loss.

Conservation efforts in East Asia focus on protecting remaining natural habitats and maintaining genetic diversity within wild goldfish populations. Several regions have implemented habitat restoration programs targeting degraded wetlands and spawning areas essential for population sustainability. These initiatives often involve partnerships between government agencies, academic institutions, and local communities to address watershed-scale conservation challenges.

Paradoxically, goldfish conservation presents unique challenges due to their dual status as valued ornamental species and problematic invasive organisms. Management strategies must balance protecting native populations while controlling feral populations that threaten indigenous aquatic ecosystems. This complex conservation landscape requires sophisticated approaches that address both species preservation and ecosystem protection simultaneously.

Human Interaction

Goldfish represent humanity’s longest-running aquaculture experiment, with domestication beginning over 1,000 years ago during China’s Song Dynasty. Selective breeding has produced dozens of ornamental varieties including fancy goldfish with modified body shapes, fin configurations, and color patterns that would be impossible in natural environments. This ancient partnership between humans and goldfish has profoundly influenced both species evolution and global aquatic ecosystems.

The ornamental fish trade generates billions of dollars annually, with goldfish comprising a significant portion of this market. Modern aquaculture facilities produce millions of goldfish yearly for pet stores, educational institutions, and research facilities worldwide. However, irresponsible pet ownership and intentional releases have established feral populations that often become ecological problems requiring expensive management interventions.

Educational and research applications utilize goldfish extensively due to their hardiness, availability, and well-understood biology. Scientific studies spanning behavior, physiology, genetics, and ecology have employed goldfish as model organisms, contributing fundamental knowledge to fields ranging from neuroscience to environmental toxicology. Their role in environmental monitoring programs helps assess water quality and ecosystem health across diverse aquatic systems, as discussed in various fishing tips for beginners resources.

Interesting Facts

Goldfish possess remarkable longevity potential, with documented lifespans exceeding 40 years under optimal conditions. The oldest recorded goldfish, named Tish, lived to 43 years old, challenging common misconceptions about their brief lifespans in small aquaria. This longevity reflects their robust physiology and adaptability to diverse environmental conditions.

Contrary to popular belief, goldfish demonstrate sophisticated memory capabilities extending far beyond the mythical three-second attention span. Scientific studies have documented memory retention lasting months, with individuals learning complex spatial navigation tasks and recognizing human caregivers. These cognitive abilities support their success in novel environments and contribute to their effectiveness as invasive species.

Wild goldfish can achieve remarkable sizes when provided adequate space and nutrition. The largest recorded specimen measured 47 centimeters and weighed over 5 kilograms, demonstrating the dramatic difference between confined ornamental fish and those in natural environments. Such size differences highlight the importance of proper habitat for fish health and development, principles that apply broadly to techniques covered in basic fishing techniques.

Goldfish exhibit the ability to produce ethanol in their bodies during oxygen-depleted conditions, allowing survival in frozen ponds where other fish would perish. This remarkable physiological adaptation enables them to metabolize carbohydrates anaerobically, producing alcohol concentrations that would be toxic to most vertebrates but allowing goldfish to survive extended periods without dissolved oxygen.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long do goldfish actually live in proper conditions?

Goldfish can live 10-30 years with appropriate care, habitat space, and nutrition. The common belief that goldfish live only a few years stems from poor keeping conditions in small bowls without proper filtration or water quality management. In optimal environments such as large aquaria or outdoor ponds, goldfish regularly achieve lifespans exceeding two decades.

Can goldfish survive in natural water bodies year-round?

Yes, goldfish demonstrate remarkable cold tolerance and can survive freezing conditions in temperate climates. They enter a state of reduced metabolic activity during winter months, surviving beneath ice cover in ponds and lakes. This adaptation explains their success as invasive species across diverse geographic regions and climate zones.

Do goldfish really have three-second memories?

This is a persistent myth contradicted by extensive scientific research. Goldfish demonstrate memory capabilities lasting weeks to months, learning complex behaviors, recognizing individuals, and navigating spatial environments effectively. Their cognitive abilities support sophisticated behaviors including social learning and environmental adaptation.

Why are goldfish considered environmentally harmful in some areas?

Introduced goldfish populations can disrupt native ecosystems through competition for resources, habitat modification through their feeding behavior, and potential disease transmission to indigenous fish species. Their hardy nature and rapid reproduction enable them to establish dominant populations that alter aquatic community structure and ecosystem function, similar to challenges addressed in finding good fishing spots where invasive species impact native fish populations.

Conclusion

The goldfish stands as a remarkable example of evolutionary adaptability and human influence on global ecosystems. From their origins in East Asian watersheds to their current status as both beloved companions and ecological concerns worldwide, goldfish demonstrate the complex relationships between human activities and natural systems. Their success across diverse environments reflects exceptional physiological resilience while highlighting the responsibilities that accompany species introduction and management. Understanding goldfish ecology, behavior, and conservation needs provides valuable insights into freshwater ecosystem dynamics and the ongoing challenges of balancing human interests with environmental stewardship.

Share The Article:

More Fish Species:

-

Green Swordtail

The Green Swordtail (Xiphophorus hellerii) represents one of the most recognizable and ecologically significant freshwater fish species in both…

-

Shubunkin Goldfish

The Shubunkin Goldfish (Carassius auratus) represents one of the most popular and visually striking varieties of goldfish kept in…

-

Delta Tail Betta

The Delta Tail Betta (Betta splendens) represents one of the most recognizable and sought-after varieties within the aquarium trade,…

-

Molly Fish

The Molly Fish represents one of the most adaptable and ecologically significant freshwater species in tropical and subtropical regions…

-

Pacu Fish

Pacu fish represent one of South America’s most ecologically significant freshwater species, encompassing several closely related members of the…

-

Pristella Tetra

The Pristella Tetra (Pristella maxillaris) stands as one of South America’s most distinctive freshwater aquarium species, renowned for its…

Discover

-

Utah Fishing License Guide: Costs, Requirements & Hidden Tips for 2025

When I first planned a fishing trip to Utah’s beautiful waters about a decade ago, figuring out the licensing…

-

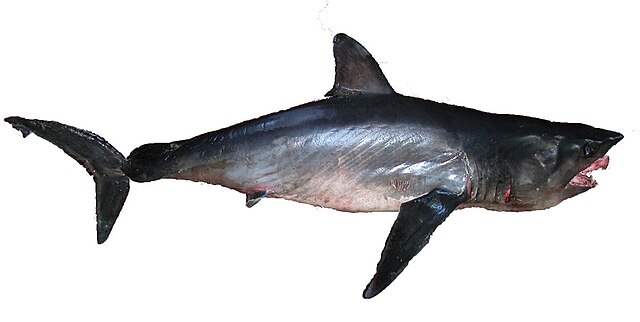

Longfin Mako Shark

The Longfin Mako Shark represents one of nature’s most enigmatic and misunderstood predators, embodying both the raw power and…

-

How to Fish with Dry Flies: Beginner’s Guide to Surface Action

There’s something almost magical about watching a trout rise to sip your dry fly from the surface. I still…

-

Fly Fishing | How to fly fish in 2025?

Fly fishing has changed a lot since I first picked up a rod back in the mid-90s. The fundamentals…

-

Fishing Tips for Beginners: An Expert Guide to Your First Successful Catch

Getting started with fishing can feel overwhelming. Trust me, I’ve been there – staring at walls of equipment, trying…

-

California Fishing License Guide: Costs, Types & How to Buy (2025)

Getting your California fishing license might seem like a hassle, but it’s actually pretty straightforward once you know the…

Discover

-

Red Devil Cichlid

The Red Devil Cichlid stands as one of Central America’s most formidable and captivating freshwater predators, renowned for its…

-

Rainbowfish

Rainbowfish represent one of the most visually striking and ecologically significant groups of freshwater fish found across Australia, New…

-

How to Become a Better Fisherman in 2025: Master These 5 Skills

There’s something magical about that moment when your line goes tight and you feel the unmistakable pull of a…

-

Crown Tail Betta

The Crown Tail Betta stands as one of aquaculture’s most distinctive ornamental fish, renowned for its dramatically elongated, spiky…

-

Discus Fish

The Discus Fish (Symphysodon spp.) stands as one of the most revered species in the freshwater aquarium trade, earning…

-

7 Best Fly Fishing Rods for Beginners in 2025 (Tested by a Pro)

Ask any fly angler what their most important piece of gear is, and most will point to their rod….